Curated by Curates

How a museum in Cologne is trying to improve relations between the Church and art

How a museum in Cologne is trying to improve relations between the Church and art

One probably wouldn’t assume that the world’s largest collection of works by Paul Thek is in the hands of a Catholic institution: The Museum of the Archdiocese of Cologne, known as Kolumba since its move to the impressive Peter Zumthor-designed building in 2007. In its current exhibition Art is Liturgy (which runs till 15 August) the museum has put many of its Thek pieces on display. Jan Kedves speaks to Kolumba director Dr. Stefan Kraus.

Jan Kedves Dr. Kraus, how does Catholic curating work?

Stefan Kraus Just the same as Catholic breathing, eating, swimming, shopping … the way we understand curating is based on the original sense of the word: we take care, we look after the works in our collection, from which the exhibits for all of our shows are drawn. In concrete terms this means that on issues of content, instead of starting with ourselves, as a team of curators, we question the works, looking for the best possible way of presenting them.

It sounds almost as if relations between the Church and art are easygoing …

SK Dealing with art has been of great importance to the Church for many centuries. Religion and art both address key questions of our existence, engaging with them afresh again and again. Kolumba represents an attempt to re-establish normal relations between the institution of the Church and art, but without excluding obvious sources of friction.

… for example without excluding the work of a gay artist like Paul Thek who was critical of the Church’s attitude towards homosexuals, divorcees and women?

SK Art is not a matter of intention, but of impact. An art work must get its meaning across independently of the artist – so it’s not about the artist, it’s about what is already beginning to move away from the artist in the moment of making. Consequently, the facts of the artist’s life are of little consequence here, however interesting it sometimes is to find out about them. Concerning the critical element, I don’t see that as a challenge only to the Church in dealing with art. For any person who engages with art, it possesses a subversive power to call that person into question. The current relationship between art and politics might be considered in a similar way.

After Thek’s death in 1988, Kolumba built up the world’s largest collection of his works. How did that come about?

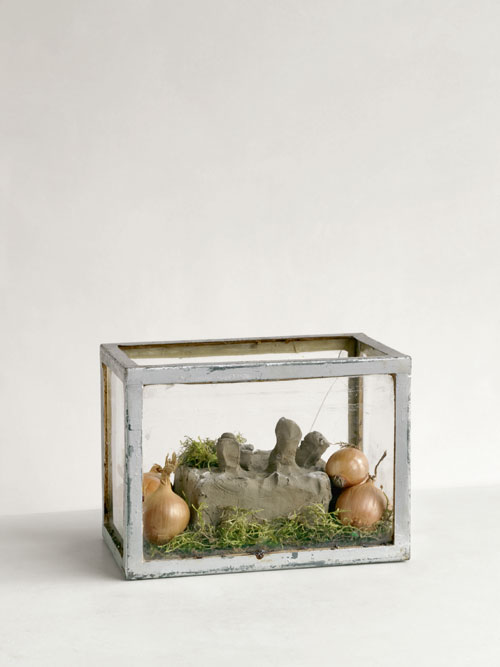

SK Besides works by Joseph Beuys, Antoni Tàpies and Jannis Kounellis, the purchase of Thek’s Fishman in Excelsis Table [1970/1] was among the first major acquisitions in the early 1990s. At that time, Thek was exclusively an artist’s artist. Our collection of his works was built up with great determination in just a few years, and then supplemented by the gift of a body of early works previously owned by his sister. There was no way anyone could have foreseen his triumphant rediscovery, a little luck was also involved.

In Paul Thek. Shrine, the catalogue accompanying the museum’s current exhibition, Thek’s gallerist of many years Michael Nickel says: ‘He was often quite a trickster, especially when it came to red herrings regarding potential meanings or interpretations of his work.’ To what extent might a Christian reading of Thek fall victim to such a trick?

SK Your question implies the possibility of relating objectively to art. Art history is still suffering from this notion, but I don’t share it. Art only comes into existence when I get involved as a viewer, bringing my entire subjectivity. As a Christian, then, I have no choice but to experience and interpret art against the background of my Christian beliefs and values – even if this means doing so in a critical way that calls these values into question. But in the case of Thek, it is hard to ignore the fact that he engaged throughout his life with the central questions of Christianity. The discovery of a written description of one of his Fishmen as ‘Birth and Death Fishman in Excelsis – Great Flesh Explosion’ thus confirmed our view of this state of uncertainty between life and death.

How do you understand Art is Liturgy, the title of the museum’s current exhibition?

SK The title is quoted from a comment made by Thek in conversation with Harald Szeemann, when he named the late-medieval theologian Meister Eckhart and the Holy Scripture among his key sources. The exhibition explores this claim, as well as the possibility of its opposite – the extent to which liturgy itself might be art. Liturgy gives a communicable form to belief, allows it to be experienced via the senses, becoming transformed into a reality of its own. This claim to a distinct reality beyond the factual, the rational or even the illustrative is something shared by art and religion.

The Vatican is planning its own pavilion at the Venice Biennale this year for the first time. As he revealed in an interview with the German FAZ newspaper, Gianfranco Ravasi, the Vatican’s Culture Minister, firmly intends to move away from the clichéd image of ‘Church art’. Will you be advising him?

SK There is no contact between Cardinal Ravasi and the museum, I don’t even know if he’s ever visited us. Kolumba is a product of Cologne and was developed entirely for its specific location, not intended as a model for others. Different places call for different approaches. One should also remember that what has been taking place to great public acclaim over the last five years in the new building by Peter Zumthor came out of the museum’s old location in a process of open discourse starting in 1992. The continuity in curatorial staff also plays a part in this process. Incidentally, it was Cardinal Meisner who decided that this work should be done by art historians and not by theologians.

Cologne’s Cardinal is not known as a friend of contemporary art. He was very critical of Gerhard Richter’s window for the cathedral.

SK Although it is hard to reconcile this fact with the usual clichés, Cardinal Meisner actually made Kolumba possible, he initiated it, defended it against many attacks, and gave us the chance to develop and to take responsibility for it.

In 1995, Gerhard Richter chose not to sell his Baader Meinhof cycle to Kolumba because he thought a Catholic institution wasn’t an appropriate home for it.

SK It remains one of the biggest disappointments in building the Kolumba collection that Richter finally chose MoMA, as he had just promised us the cycle in February 1995, after lengthy discussions with us. Of course, it’s up to individual artists to decide whether or not they feel their work would find a good home at Kolumba. Richter’s wonderful window for the cathedral and his acceptance of the Art and Culture Prize of Germany’s Catholics are clear evidence that he is not hostile to Catholicism.

Does Kolumba sometimes sell pieces from its collection?

SK Once something is in the collection, it stays there. Otherwise, I don’t know how we could motivate our donors – in recent years, the collection has benefited more from donations than from acquisitions. That is the true potential of our museum: that the collection will outlive the egocentric vision of its various curators.

Dr. Stefan Kraus is an art historian who became the director of Kolumba in 2008. He co-edited Paul Thek. Shrine , a catalogue of the museum’s Thek collection.