The ‘Schlock Apocalypse’ of John Boskovich

Boskovich wanted to inhabit a place that made no distinctions between sculpture and furniture, curation and decor, art and everyday life

Boskovich wanted to inhabit a place that made no distinctions between sculpture and furniture, curation and decor, art and everyday life

Who was John Boskovich? In ‘Psycho Salon’, the late Los Angeles artist, filmmaker, writer and noted recluse – who died in 2006 aged 50 – is everywhere and nowhere, a phantom presence inside a space packed with his stuff, a personage that flickers like a candle. Housed in a back unit of the historic Granada Buildings, which itself creaks and reeks of an older Los Angeles, O-Town House has resurrected an artist whose legacy had been at risk of being buried. In addition to dusting off an array of Boskovich’s many works, which have rarely been shown over the past twenty years, the gallery is the first to ever take a stab at restaging the ‘Psycho Salon’, the living room inside Boskovich’s fabled, hyper-designed digs in West Hollywood.

From 1996 until the artist’s death, ‘Boskostudio’, as he called it, was more playhouse than mere house, a set stage for his own self-invention. Citing Joris-Karl Huysmans’s decadent novel À Rebours (Against Nature, 1884) as inspiration, Boskovich used the space to put theory into practice: he wanted to inhabit a place that made no distinctions between sculpture and furniture, curation and decor, art and everyday life. Nothing could appear aesthetically unconsidered; every inch of the house oozed intentionality.

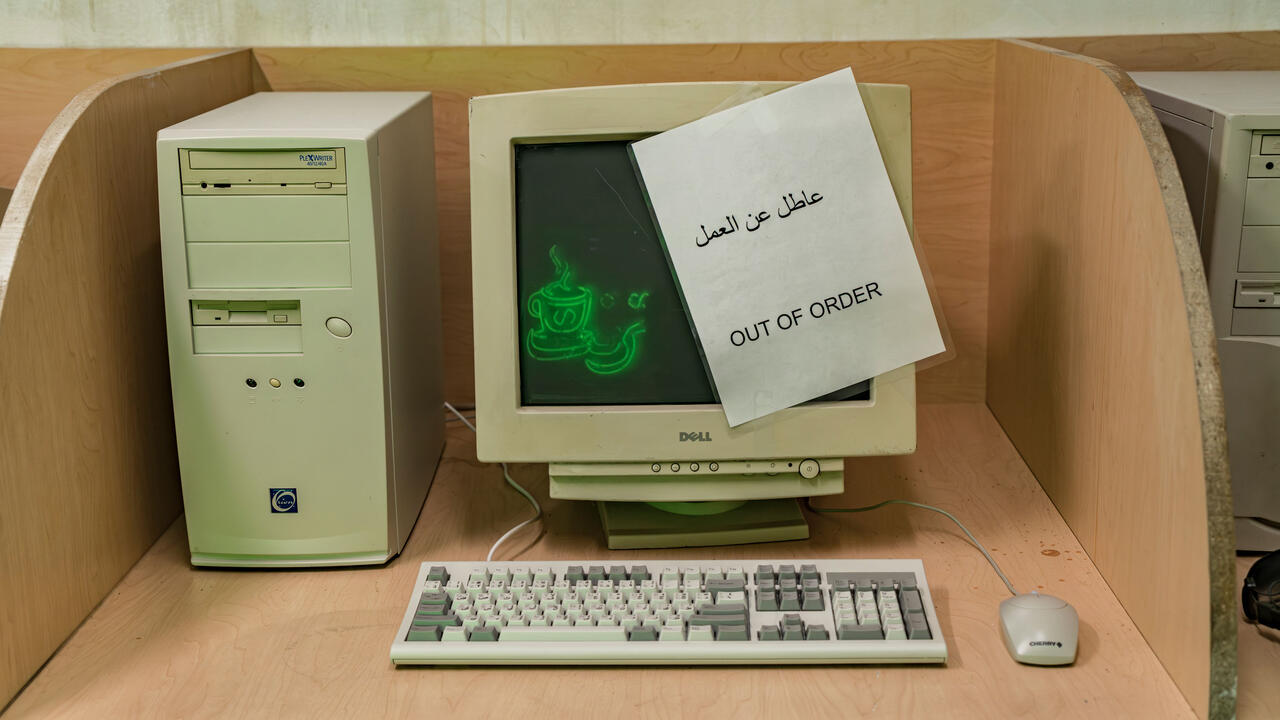

Don’t call it décor – think of it more as mise en scène. Emailing his friend, the Semiotext(e) publisher Hedi El Kholti in 2002, Boskovich likened his concept to ‘a Fassbinder set where no movie ever occurred.’ The scheme was ‘schlock apocalypse’: vinyl upholstery, animal prints, occult motifs and gaudy hues covered the place. Lines from cherished poems were emblazoned high up on walls, like omniscient narrators; security cameras and monitors abounded, the much-needed spectators for Boskovich’s stagecraft. Writing for Interior Design magazine in 1997, David Rimanelli remarked that Boskostudio seemed to ‘theatricalize insecurity’, perhaps even parodying its creator’s desire to take shelter in such a synthetic existence.

For several reasons, there’s a haunted, funereal feel to the gallery’s main exhibition space, devoted to a studious remake of the Psycho Salon. The gallery walls match the putrescent, avocado green of the original, while Boskovich’s blood-red curtains cloak the large windows. His Untitled “Designer” Carpet (1993) – a circular, black and red rug, patterned with a giant pentacle – blankets the floor. The Hare Krishna Lamps – found Krishna sculptures, topped with bulbs and shades – hover on black Formica bases, which display quotes from T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets (1941). Untitled Navaho Rug with Ginsberg Text drapes over a round ottoman: ‘America’, the embroidery reads, ‘I’m putting my queer shoulder to the wheel.’ The inscription rings out as the artist’s voice, loud and clear. We can only view these objects through the veil of their past lives, how they inhabited Boskovich’s home. Here, they appear almost hollow, like spectres of their former selves, props without a master.

Otherwise, Boskovich’s standalone artworks feel wholly alive. In his ‘Rude Awakening’ series, hazy polaroid pictures are coupled with succinct self-declarations. The head of a plastic honey bear bottle peeks up from the bottom edge of one polaroid, flanked by its shadow; ‘I am successful and prosperous,’ the text reads. Superimposed on a man’s erect penis and tanned legs: ‘I have a limitless capacity for joy.’ These mantras were taken from a self-help book that someone gave to a former boyfriend, who was dying of AIDS. Boskovich’s satire is shrewdly whispered.

In several gestures towards self-portraiture, the artist himself seems wholly present. Upstairs, a grid of 20 photographs reveals Boskovich tossing and turning in a bed of ghostly, white sheets, floating above a deep-black void. On the opposing wall, his phone number is screen-printed on a small, found watercolour drawing, and his social security number engraved on a Kennedy half-dollar coin. (Apparently, only one person, the young son of a collector, ever called.) Back downstairs, a plastic honey bear is encased in a small vitrine, under a spotlight. It’s more than half-empty of old honey, its cap crusted over. We see the artist seeing himself, a smiling vessel smeared by the sticky mess of life. Perhaps even more, we see his desire to capture this, contain it, make sure it can be seen forever.

Main image: John Boskovich, Clean & Sober/Sober 'N Crazy, 1997, oil on mahogany panels, mahogany frame, 11 × 68 × 3 cm. Courtesy: O-Town House, Los Angeles.