Signs of the Times

Dan Fox looks at the work of Mark Bradford, who represents the US at this year’s Venice Biennale

Dan Fox looks at the work of Mark Bradford, who represents the US at this year’s Venice Biennale

Amongst the many failings that would disqualify me from being an art historian is the fact that I can’t see abstract painting as anything but a form of figurative art. I blame it on seeing, as a teenager, reproductions of Piet Mondrian’s tree paintings from the early 1910s: ever-thickening patterns of branches that flattened space, an evolution from figuration to some sort of Platonic essence of tree. The idea – erroneous, perhaps, but persistent – that all abstract painting is a form of distillation from life has stuck with me. After all, these paintings were made by real people who eat, breathe, see, speak, hear, smell, shit, sleep and feel. They are real objects for people to find on postcards or in books in shops, homes, libraries, schools, on TV and, maybe, if you are one of the lucky ones, up close in a museum. Abstraction is grounded in experience.

Neither abstract in the metaphysical sense of representing some sublime form of cosmological vibration nor in the original Latin sense of something being ‘drawn away’, abstract painting is always about people: it tells you about the scale of bodies, about how minds perceive colour and form, about the kinds of gestures a hand, an arm and an eye can make in concert with each other. Like all art, an abstract painting can tell you a lot about the time, place and society in which the artist made it as well as the viewer who enjoys it. I’m with the poet Paul Celan when he says: ‘I cannot see any basic difference between a handshake and a poem.’ Claudia Rankine unpacks Celan’s line in her book Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric (2004): ‘The handshake is our decided ritual of both asserting (I am here) and handing over (here) a self to another. Here. I am here.’ She goes on to explain: ‘One meaning of here is “in this world, in this life, on earth. In this place or position, indicating the presence of,” or, in other words, I am here.’

So, shake hands with Mark Bradford. His abstract paintings are neither abstract nor paintings. We call them paintings because that is the convention for flat images made by hand that hang on a wall, and we call them abstract because they might remind us of, say, a painting by Sam Gilliam, Al Loving, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Cy Twombly or Jack Whitten. Other historical comparisons might include nouveau réalisme artists such as Raymond Hains, Mimmo Rotella and Jacques Villeglé, who made collages using torn posters found on the streets of Paris. To my mind, they are, rather, ways of saying: ‘I am here.’ Here in the landscape of south central Los Angeles, where he lived until the age of eleven and where he now has his studio in Leimert Park. These so-called abstract paintings are, in fact, assemblages that bear witness to the changing social and economic climate outside Bradford’s studio, made primarily, though not always, from the discarded posters, carbon paper, newsprint and perm end-papers from hairdressing salons that he finds in the street. He tears, pastes, juxtaposes and overlays this material, using siliconized caulk, cord and nylon string to give these accretions of paper new, topographic shapes. (Bradford has used paint relatively sparingly throughout his career.) The resultant collages he offers are solid, evidential.

So, although Bradford’s assemblages initially seem to socialize with abstract painting, I still can’t help but come back to Mondrian’s trees: a form of image-making that is grounded in concrete realities. Given how he sources his materials, it may be more accurate to describe Bradford as a landscape artist and, like any smart landscape artist, he not only shows us the view but what structures it: history, politics, class, ownership, power. An obvious starting point would be his series ‘Merchant Posters’ (2006–09): collages made from signs he found on telegraph poles, boarded-up shop fronts and fenced-off empty lots, which speak both of entrepreneurial spirit and economic desperation. Mostly individually untitled, the ‘Merchant Posters’ look ghostly and washed out, their letter-forms soft, as if seen through a heat haze. They record need: ‘WE BUY HOUSES CASH’, ‘TRANSITIONAL HOUSING FOR MEN AND WOMEN’, ‘MY CHILD SAYS DADDY / CHILD CUSTODY DIVORCE – VISITATION.’ Their language reflects changing populations in the neighbourhood: black, Hispanic, Korean. Their sense of hustle and community describes a version of south central Los Angeles that cuts against the mainstream-media stereotype of the area as rife with crime and desperation: ‘HAIR BY DESIGN BOOTHS FOR RENT’, ‘BOYS BASKETBALL 5TH 6TH 7TH 8TH GRADE TEAMS FORMING’, ‘FORM YOUR OWN CORPORATION’.

If the ‘Merchant Posters’ are, conceptually speaking, Bradford’s miniatures – crystalline notations of local moods and needs – then his larger works confront bigger forces of social history beyond Leimert Park and beyond Los Angeles. Emblematic of this might be his 2006 painting Scorched Earth, a response to the 1921 race riot in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which resulted in the decimation of Greenwood, nicknamed ‘Black Wall Street’ – an area that, at the time, was one of the most successful black business centres in the US. The riot was started after a young black man was accused of assaulting a white woman in an elevator. Following confrontations between white and black mobs outside the Tulsa courthouse, white rioters looted Greenwood, attacking African-American residents and businesses.Greenwood was destroyed (aerial bombardment from private planes was also used) and nearly 300 people died. According to the Tulsa Historical Society, a further 6,000 black Tulsans were detained by the authorities for over a week. The top of Bradford’s painting is capped with a fiery red strip, across which arcs what could be a vapour trail, made from vertical rectangular strips. It leads the eye into the charred and blackened centre of the composition, which suggests an aerial view of a city-grid layout, inflected with additional small, rectilinear windows of bright colour. Scorched Earth flickers between the representational and a more inchoate form of image, as if it’s speaking about something we know but can’t quite see. You could be looking down on Earth from a satellite or pressing your face against the television screen watching news of the latest demonstration against police violence, your eyes up close to the raster patterns that, from a distance, coalesce into media images. (Pixellation is, after all, just an update of what Georges Seurat demonstrated in his pointillist paintings of the 19th century.) In Scorched Earth, the detritus of Leimert Park is repurposed to represent a shameful episode in US history: in Bradford’s hands, the paper fragments tell other, deeper stories. (The ‘here’ of Los Angeles becomes a lens that telescopes perspectives, offering a way to think about things that are distant in both time and space.) You could say this is a form of archaeology: Bradford’s process often involves scraping, lacerating, routing and digging into the surface of his works, revealing buried layers, oxygenating a smothered colour here and resubmerging it there. But, in the artist’s hands, digging and excavating result in building – both a picture and a body of knowledge. (What many artists call research and reference is often simply another way of talking about collage: putting one thing next to another and letting them resonate.)

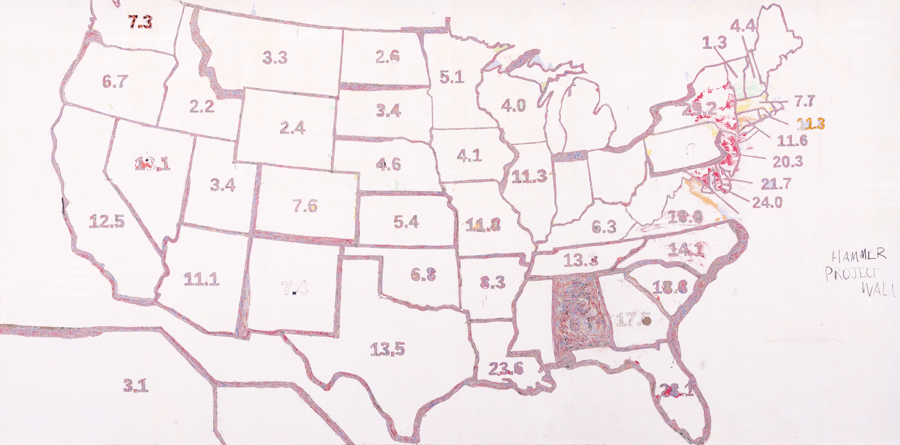

‘Scorched Earth’ was also the title of Bradford’s 2015 solo exhibition at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. Alongside a suite of 12 paintings and an audio work titled Spiderman (2015) – in which the artist writes and performs a stand-up comedy routine that critiques Eddie Murphy’s homophobic monologue in his 1983 live recording, Delirious – Bradford used the museum’s lobby wall to create a huge outline of the US. He gouged the contours of the country deep into the whitewashed walls, exposing washed-out trails of colour from 29 previous murals. In bruised purples, greens and blues, these buried artworks took on the forms of the 50 US states; in the centre of each was scraped a figure, representing the number of people out of 100,000 who had been diagnosed with AIDS by 2009. Here, again, we see Bradford speak through the landscape: an archaeological dig on the walls of a museum creates a picture of the nation as he sees it.

As this monumental lobby mural suggests, Bradford’s experience as a young, gay, black man during the AIDS crisis in the 1980s has been central to his work. Myriad other contexts and situations – from growing up working class, without access to museums or galleries, to race relations in LA after the 1992 riots – have made Bradford as much an artist motivated by social justice as anything. A recent video work, Deimos (2016), shown at the old Roxy roller disco in New York, which is now home to Hauser & Wirth, uses ricocheting rollerskate wheels and a Sylvester disco soundtrack to deeply poignant effect: a biographical nod to the era of his youth. The music plays as if in search of someone to dance to it while the wheels bounce around with no one riding them; the skaters have vanished, died. Bradford’s Art + Practice organization – an exhibition and social space in Leimert Park that, in collaboration with the youth services group RightWay, provides job training and education for teenagers coming out of foster care in south Los Angeles – is testament to an admirable ethics at the core of his activities.

This year, Bradford is representing the US at the 57th Venice Biennale. His optimistically titled show, ‘Tomorrow Is Another Day’, will feature paintings and sculpture but will also encompass Process Collettivo (Collective Process): a long-term collaborative project with Rio Terà dei Pensieri, a Venice-based co-operative that works with the inmates of a women’s prison on the island of Giudecca to make bags made from recycled signs and posters. The project is funded by Bradford and the profits are channelled straight back into the co-operative.

Under Trump’s new kleptocracy, we need, more than ever, to be pragmatic and determined to push back at a government hell-bent on taking away from the socially marginalized and vulnerable their few state-subsidized safety nets and educational opportunities. Bradford’s work embodies a generosity of spirit that, for all the cruelty of White House politicians, can never be occluded within the US landscape. As Rankine writes of Celan: ‘In order for something to be handed over, a hand must extend and a hand must receive.’

Mark Bradford lives in Los Angeles, USA. He will represent the US at the 57th Venice Biennale, Italy, from 9 May to 22 November 2017. His video Spiderman (2015) will be exhibited alongside Derek Jarman’s film Blue (1993) at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA, until 30 July. The exhibition ‘Shade: Clyfford Still/Mark Bradford’ is at the Denver Art Museum and Clyfford Still Museum, Denver, USA, until 16 July.

Main image: Mark Bradford, Scorched Earth (detail), 2006, mixed media, 242 × 300 × 6 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Hauser & Wirth, London, New York and Zurich