Slanted and Enchanted: Oriane Durand on the Year in Shamanism and Superstition

The curator, author and director of Dortmunder Kunstverein reflects on a year of shows dealing in magic and mythologies

The curator, author and director of Dortmunder Kunstverein reflects on a year of shows dealing in magic and mythologies

In 2018, I found myself drawn to shows dealing with magic and shamanism, and so I look back at the year with a sense of enchantment. Tender entanglements of dystopian visions and individual mytholo-gies are part of a recent artistic trend characterized by hybridity, transformation and a belief in material.

I was deeply impressed by Paul Spengemann’s ‘Whoa, Hoo-ah Huh!’ at the Artothek in Cologne. In the single, large room, Spengemann installed a projector and projected a loop, roughly ten minutes long. In the video, the shadow of a dragon swings back and forth. For a moment, the shadow’s tail strokes the edge of the frame. Then the dragon flies away, disappears from the projection for a few seconds and eventually returns as a shadow. The sound of fluttering wings and the dragon’s wheezing come at you from all sides; the beast is nearby. The use of special effects is relatively slight, especially when one considers that dragons are the most expensive creatures Hollywood animates. Spengemann used an open-source 3D software for the animation, and likewise an open-source plugin for the sound, which transforms the artist’s voice into that of a predator. In the end, the dragon is overwhelmed by an avalanche of stones. But thanks to the loop, he soon rises again like a phoenix from the ashes. After I left the exhibition, I was walking along the Kölner Dom and suddenly felt like the gargoyles above would descend from their stony perches to get a bite of me.

In this spectrum of the magical and sinister, Korakrit Arunanondchai’s ‘With history in a room filled with people with funny names 4’ – an immersive installation of sculptures, sounds, and videos at the J1 in Marseille – animated the ocean floor, or rather the ‘historic sediment [of Marseille]’ and ‘the layers of civilization it consists of’, to quote the exhibition text. Several sculptures of clams and ocean debris were distributed over a floor covered in tar-like soil. They seemed lost in the enormous warehouse. Some of the piles took the shape of sea creatures with human faces. It seemed as though the ocean had drawn itself back, revealing its contents. One encountered petrified forms, perhaps leftovers from our history, or maybe creatures revived after a period of mummification. The objects on view seemed to be in a transient state. The temporalities of Arunanondchai’s installation opened up my imagination for many scenarios, from the dystopian to the most transformative. I was reminded of Colm McCarthy’s film The Girl with all the Gifts (2016), and specifically of all the possibilities that open up for a girl when she’s half-human, half-zombie. The greatest transformations aren’t necessarily determined by technology.

Not far from Cologne, the Leopold-Hoesch-Museum in Düren presented a two-person show of Paul Sochacki and Raphaela Vogel in fall. (I knew Raphaela Vogel’s work well since I curated her first solo exhibition, at the Bonner Kunstverein, in 2015.) The contrast between the two positions managed to create a special intensity for me. Paul Sochacki’s paintings often have clear political messages, though their pastel colours are soft and the lines tremble with lightness. Sometimes the characters and objects depicted felt like they were floating in the canvas; at others, they seemed isolated, abandoned. Raphaela Vogel’s installations, installed in alternation with Sochacki’s fine paintings, are sometimes monumental, sometimes not, sometimes with, sometimes without projection, but they are always one thing: loud. Colours (mostly dark and earthy), materials (animal skins or dripping plastics), objects (hookahs, tombstones, or animal skulls) – everything points back to a shamanic vocabulary. Like a sorcerer trying to drive out pain and desire, Vogel dives into the dark side in order to create works with an extremely expressive power. Two individual mythologies that each question power relations in their own way: on one hand, an ostensible naiveté painting heavy themes under a veil of tenderness, on the other a wild scream, the result of a confrontation between technology and an archaic, animalistic force. Like the story of the planets Anarres and Urras in Ursula Le Guin’s Dispossessed (1974) – whose death marked the beginning of 2018 – the exhibition lets two worlds collide.

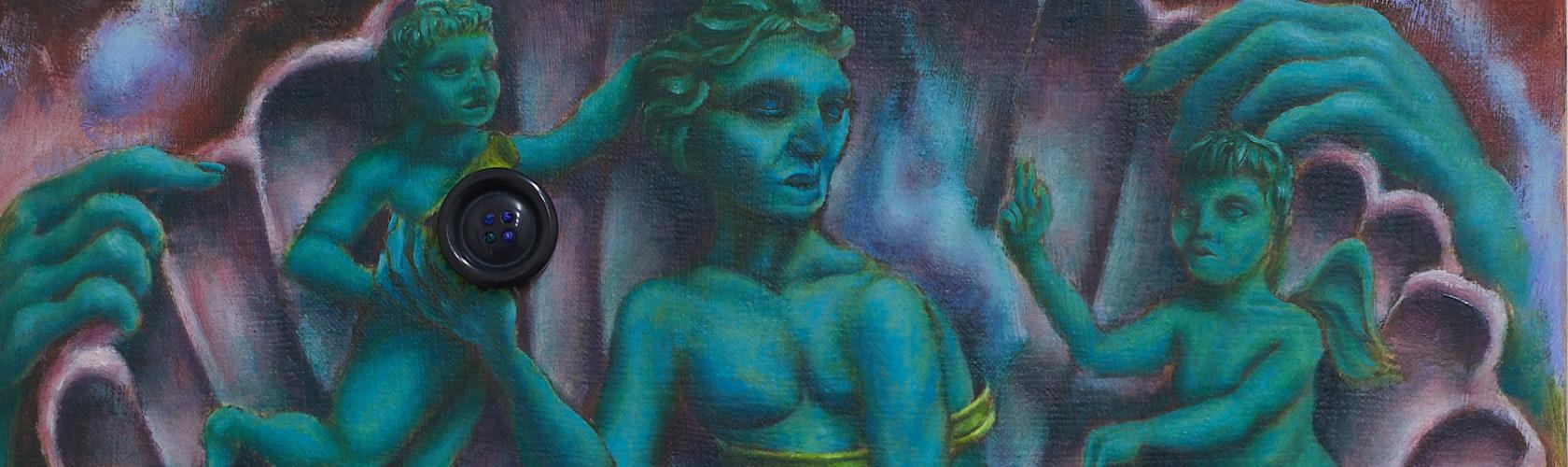

The year ended for me with the dark, surreal, and delirium-filled exhibition ‘Bonaventura Jannis Mar-witzle’ by Jannis Marwitz at Damien & The Love Guru in Brussels. The German artist’s paintings achieve an extreme density of colour and form: the green in the birth of Venus in Ohne Titel (2018) seems greener than green; the pink in Der Hurrikane (2018) is more than pink; and the eyes in the portrait Ohne Titel (2018) are more than eyes. The paintings feel like they’re exploding in their abundance of detail, makeup, and exaggerations. Like a magic cauldron, filled with brew of over 5000 years of art history, Marwitz tries to accommodate a whole database in a limited two-dimensional surface. His paintings create an allegory for the internet that forces my gaze into an unhealthy hypertrophy while hypnotizing me with their disturbing humour.

Main image: Jannis Marwitzle, Untitled (detail), 2018. Courtesy: the artist, Damien & The Love Guru, Brussels and Lucas Hirsch, Düsseldorf; photograph: Alexey Shlyk