Something Like a Portrait of Louise Bourgeois

A mother’s death, a father’s disinterest: Jean Frémon’s semi-factual biography of the artist captures a life beyond repair

A mother’s death, a father’s disinterest: Jean Frémon’s semi-factual biography of the artist captures a life beyond repair

We are not creatures who walk in straight lines, you and I, nor are we concerned with constancy. We live our lives as light moves between shards: one thing, then a next, then another, then another again. Refraction follows refraction always.

Jean Frémon’s Now, Now, Louison, a semi-factual, semi-fictional portrait, constructed from memory, of the life of Louise Bourgeois, cuts a similarly jagged path. A rumination on ‘a way of feeling less alone’ leaps to: ‘And, of course, the fan didn’t work.’ A buckling account of the death of Bourgeois’s mother rips back to that self-same concern: ‘OK, so is it going to work now – that fan?’ We stutter, here and forth and throughout, between time zones and narrative voices; between prose and paraphrase; between nudges of tenderness and many more of despair. We ricochet through Bourgeois’s life with little to no handle on its cast, crew or cruising altitude, all the while attempting to bring the wreckage together once more (if it were ever fused in the first place).

Frémon knew Bourgeois for more than 30 years but, as he wrote in a recent article for Granta: ‘it would be presumptuous of me to say that I knew Louise Bourgeois well.’ So is often the case with those who we hold most dear. ‘She was a complex, contradictory, unpredictable character, who really did live several lives.’ But, in spite of this freneticism, Frémon knew her intimately enough to satisfy our lowly intrigue and, bleeding between the ‘I’ of the author and the ‘I’ of Bourgeois herself (there are so many mouths), sketches out the rough idea of a childhood – one that, when not located in Choisy-le-Roi, on the south-eastern skirt of Paris, occupies a more ominous terrain of cruelty and disrepair.

Central to these formative stages were Bourgeois’s parents. Her mother, Josephine, died at a young age, something that left a mark on the youngest of her two daughters: ‘Thursday, September 14, 1932, an Olympian god, a murderer, a coward, being ungrateful, imbecilic, or merely jealous, struck Mother with his decree.’ The cruelty was two-fold. Not only did it strip the fledgling Louise of ‘the only person with whom [she] felt secure’, it also left her to the brutal disinterest of her father, a man who had failed to hide his affairs from his children and who, in the weeks following his wife’s death, ‘put playing cards, drinking with friends, and flirting with the maid all on hold. But little by little and one by one, he resumed his usual occupations.’

The dark mark left by Bourgeois’s father was indelible and of the blackest ink. As frequently as we wipe down the pages of Now, Now, Louison, it seeps to the surface once more. ‘All fathers’, we read, ‘are ridiculous balloons that we pop like the plumb paunches that constitute their entire catechism’. Elsewhere, the alpha’s influence is evinced with less pomp. This man was ‘a bon vivant, a self-confident, phlegmatic boaster, little given to melancholy.’ This man was ‘a male privilege, that big, fat, smug conscience, spreading ever outward.’ This man ‘wanted you to dress like a whore. And to wander the streets like a whore. Wanted people to see you as a whore.’ This man cast a shadow over a daughter not just in childhood, not just in adolescence, not just in middle age, but in totality: ‘And you, more than eighty years old, you’re still not over it’.

Bourgeois’s ongoing confrontation with her father’s ghost was equalled in intensity only by her tireless campaign to reanimate her mother’s. At a young age, she conjured her ‘watching over her brood. There she is; you see her in the corner, watchful, on the lookout, ready for sacrifice.’ With time, she became omnipresent: ‘Mother Pisaura, Mother Canopy, Mother Cyclose, Mother Uloborus, Mother Theridion, Mother Tetragnatha. Mother Louison, old spinner, I recognize you among them all’. But more often than not, when Josephine (re-)enters, it is under a therianthropic guise that we will all be familiar with. Bonjour maman: the spider.

That Bourgeois resurrected her mother as an arachnid was no surprise. The beasts spend, as she spent, their lives teasing yarn (‘Mother, the weaving princess’). They are towering, dominant, graceful. They are fragile. They will eat those who threaten their young: ‘Spiders, spiders, you never tired of remaking them, bigger and bigger. More immoderately maternal.’ But Bourgeois’s leggy reconstitutions were not immortalisations alone. They were part of a pained crusade to bolster Josephine’s maternal powers and retroactively repair a childhood that had been snatched away and shattered. They were sent into the world to cauterize the many wounds that continued to bleed. ‘You’ll give her eggs made of marble. Three of them. […] You will make a family of them. Your family.’

Frémon does not dwell on the details of Bourgeois’s artistic career, although a trail of anecdotal breadcrumbs has been sprinkled throughout and, while light, it tastes delicious. Constantin Brâncuși is ‘the bearded old rascal, arriving on foot from his native Transylvania, the hermit of the Impasse Ronsin’; Marcel Duchamp, ‘the lipless chess professor, Saint Touch-Me-Not’. The philosopher Gaston Bachelard has a rough time, as do his (and, of course, Bourgeois’s) countrymen: the French. ‘They ignored you for fifty years, and when they finally noticed that you existed, they couldn’t wait to tell you what you’d been doing. Bachelard to the rescue. The body is a house and the house a body, thank you, thank you.’ The savagery.

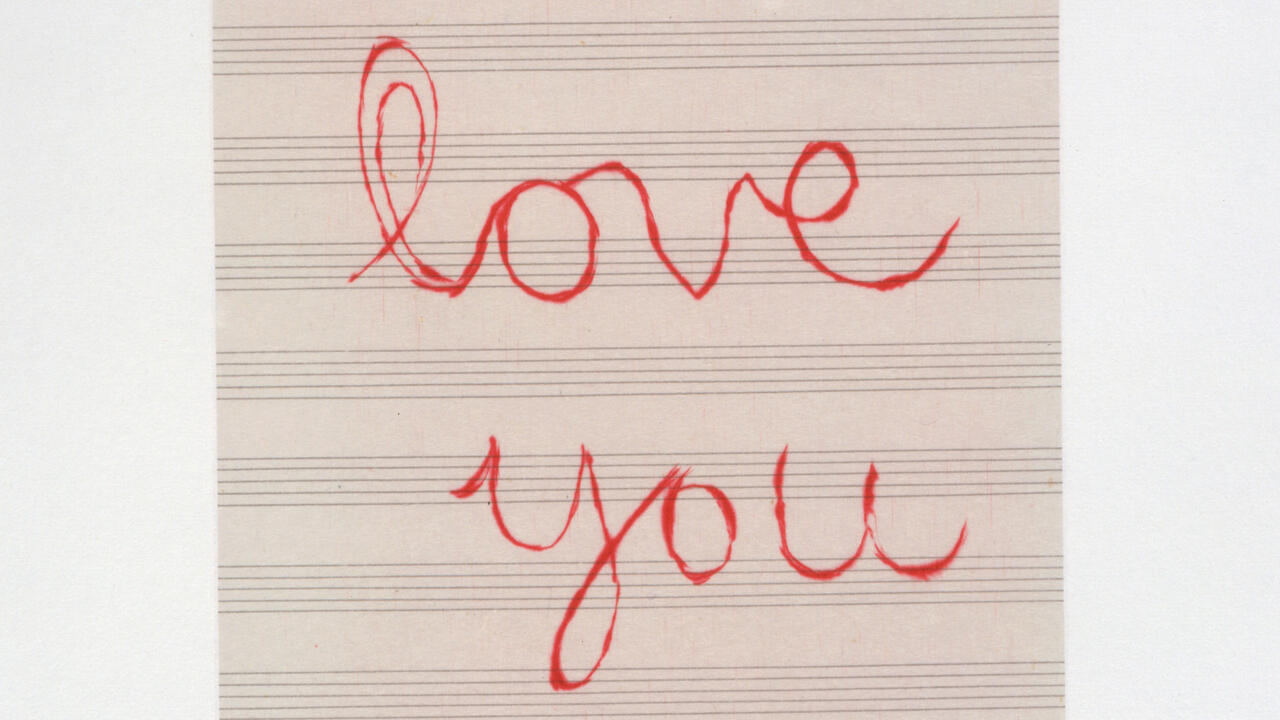

Instead, Frémon drafts an image of what art making meant to Bourgeois: namely, that ‘chaos can be controlled.’ The Bourgeois that emerges from these pages sees artistic production not as an enterprise unto itself but the physical resolution of something far less definable. ‘Aim for beauty’, we read, ‘and you get the vapid […] aim for anything else – encyclopaedic knowledge, systematic inventory, structural analysis, personal obsession, or just a mental itch that responds to scratching, and you get beauty.’ As with the spiders that protected her spindly frame; as with the watercolour breasts that engulfed her canvases; as with the children that burst from the stomachs of her mannequins: artistic practice, to Bourgeois, was some unwieldy composite of enquiry, therapy and self-definition. It was the mapping of an unmapped life. ‘So I pile, I cut, I twist, I fashion, I excavate, I carve, I model, I mold, I turn, I drip, I chisel, I polish, I sand. I am what I make and nothing else. I make, I unmake, I remake. I make fullness surge; I organise voids.’ But can one ever organise an absence? I am afraid, dear reader, one cannot. Hence, the ghost of Samuel Beckett, which animates at a mid-point: ‘From failure to failure. Fail Better, said the bilingual condor, the expert in scrawn.’

An anxiety pinches the skin of Now, Now, Louison, rousing goose-bumps that rarely plateau. This has little to do with Bourgeois’s feverish character, nor with the lingering stench of her father, nor with the absent form of her mother. It has to do with Frémon himself, who has posthumously assigned himself the role of narrator in a story other than his own. As Janet Malcolm wrote: ‘the biographer at work […] is like the professional burglar [...] breaking into a house, rifling through certain drawers that he has good reason to think contain the jewelry and money’. I, nor you, nor Frémon himself, can be certain which of these drawers contains 24-carats and which are plump with fool’s gold, but one gets the impression that our author is frantically searching for a friend, testing each candelabra with his teeth in the hope that one carries a metallic taste. ‘Who allowed you to speak in my name?’, he writes as Bourgeois, ‘And to make it all up?’ In this, Now, Now, Louison is as much a portrait of Bourgeois as it is of one who has outlasted another and is trying, in full knowledge of an impending failure, to reassemble a figure from the fragments. Perhaps life, this life, any life, is best preserved in its many bits, just as it was lived.

Jean Frémon’s Now, Now, Louison, translated by Cole Swensen, is published by Les Fugitives on 24 September 2018 and published by New Directions on 29 March 2019.

Louise Bourgeois in her New York studio, 1995. Courtesy: Porter Gifford/Corbis via Getty Images