The Power of Objects in Narrating Historical Trauma

MoMA curator Stuart Comer examines the role of everyday items as a way to approach traumatic histories

MoMA curator Stuart Comer examines the role of everyday items as a way to approach traumatic histories

This article appears in the columns section of frieze 235, based on the theme 'Time Warp'

In 1988, after finishing my studies abroad in Italy, I flew home to New York, via Geneva, two days earlier than planned. Consequently, even though originally I had been booked to travel on 21 December via London on Pan Am flight 103, I didn’t take the flight, which was tragically brought down by a terrorist attack over Lockerbie, Scotland, killing 270 people. The news in December last year that US authorities had arrested a third suspect was still triggering: an event like that is so difficult to process, especially when what could have happened did not happen. I kept my Pan Am 103 ticket – a very ordinary bureaucratic document that became a signifier of the horror of that incident – as an index to what otherwise would have been the terminal event of my life.

On 29 April 1992, a year after I moved from the east coast to Los Angeles, I was meant to go to a rave, for which a friend had made pot brownies. But, during the day, the LA riots erupted, so a friend and I stayed home instead and watched events unfold, the city completely transforming around us while the sun set. One of the uneaten brownies, along with the unused plane ticket, is still in an old filing cabinet at my parents’ home, which I never conceived of as a time capsule per se but, since I haven’t touched it in years, has become one by default.

Both objects represent false starts: signifiers of plans that did not transpire. What did, in fact, occur in each case was very violent. To that end, I suppose, I kept these items out of some need to understand that violence through its absence. Oftentimes, you think of an object as being a direct trace of something that did happen. In this case, the ticket and the brownie are remnants of what did not happen: they are anti-objects, almost, the opposite of the Proustian madeleine. In a way, we are all part of both events, since they are constituents of broader historical crises that are not yet resolved.

As a curator working at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, I help maintain, care for and present artworks and other objects that oftentimes construct histories. We preserve these things for the record, trying to narrate their historical contexts and working on the assumption that they may be shown in public. While this is a different model from an archive – a distinction that has frequently been detrimentally hierarchical – archival objects can often be as urgent as those that have been defined as ‘capital-A’ artworks. These objects’ currencies vary hugely, which has to do with the public versus private lives of objects, or even how the objects of a private life can serve a more diaristic function. What would be the ramifications of making those public, and in what context would they be given meaning?

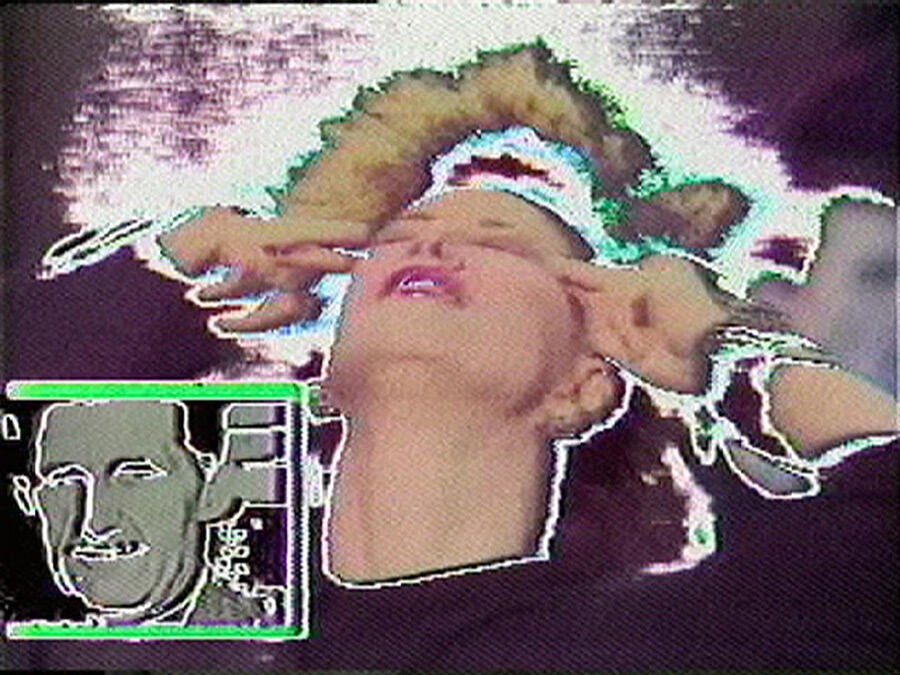

I recently opened the show ‘Signals: How Video Transformed the World’ at MoMA, which features a lot of work that documents traumatic historical events. These are image streams rather than objects, and therefore count more, perhaps, as conventional documentary evidence in terms of how you capture something like a terrorist attack or an uprising. What meaning is produced by a humble object such as a plane ticket or a pot brownie standing in for an event of such magnitude? Not much, unless you know how it was intended to be used, what the history was behind it or who was meant to use it. These objects don’t automatically connote a violent, historically transformative event. So, it comes down to how they would be used, framed or otherwise exhibited, documented or published.

I was living close to Los Angeles County Museum of Art at the time of the riots. So, the uprising was absolutely an event I was immersed in and experienced first-hand, unlike Pan Am 103, from which I was at a considerable remove. As the uprising really took hold, my friend and I watched television reports of what was happening in real time, while also witnessing the city go dark and fires erupt across the landscape. That’s a mental image I will never forget. Although the brownie – which, by now, has likely fossilized into something entirely inedible – could never adequately capture the histories of violence that led to the uprising, it nevertheless continues to remind me, vividly, of the traumatic events of that day and what transpired.

As told to Marko Gluhaich

This article appeared in frieze issue 235 with the headline ‘Time Regained’

Read more thematic columns here

Main Image: Marta Minujín, Simultaneidad en Simultaneidad, 1966. Courtesy: Marta Minujín Studio and Henrique Faria, New York