Switzerland

An enigmatic representation of the abstract social and political systems regulating our world

An enigmatic representation of the abstract social and political systems regulating our world

Galerie Bruno Bischofberger advertisement

The image above is an advertisement for Galerie Bruno Bischofberger, Zurich on the back cover of Artforum magazine, a spot the gallery has booked since the mid-1980s.1 The photographs are always of generic Swiss scenes: mountains and lakes, nuns and priests, farmers and cows, people gathering hay, making cheese or wearing traditional costumes and participating in festivals; they are largely rural and sometimes extremely odd: a close crop into, say, an image of a piece of bread or a laughing face blown up to fill the page. These homely Swiss snapshots form a direct contrast to the roster of gallery artists listed across the image. Ordered according to business categories pertaining to their availability for purchase – ‘In Exclusivity’, ‘Representing’ and ‘Works by’ – the artists are only signalled by their last names: Tinguely and Sottsass, Clemente and Cucchi, along with a regular group of 1980s’ American luminaries, such as Condo, Halley, Salle, Schnabel, Basquiat and Warhol. These advertisements enigmatically circle the semantics that determine art-world consumer habits and viewing conditions. These images of Switzerland conform to a picturesque stereotype; the story they tell is, of course, a fiction of sorts: wealth and cultural logic masked by the minimal presentation of gallery information. There is a collision of meaning here: what is being shown to us and what is actually being represented are two different things. This technique both animates and obscures, rendering abstract what is in fact an extremely precise system of value and information exchange, of public relations, art and commerce.

Sherrie Levine ‘After Walker Evans’ (1981)

Sherrie Levine’s seminal work of appropriation ‘After Walker Evans’ (1981) consists of re-photographed bookplates from a Walker Evans exhibition catalogue. Evans’ photographs of poor sharecroppers, taken in the 1930s for the USA’s Farm Security Administration, are icons of pioneer photography. The impoverished interiors and stoic poses captured by Evans in such a minimal manner were subsequently fetishized for their perceived authenticity and beauty. Levine’s re-presentation of the Evans works as her own is an astute artistic strategy that questions not only the power relations inscribed in the action of the ‘master’ photographer Evans but also the subsequent art-historical canonization and market value of the original works. Property relations, patriarchal authority, authorship and originality are all brought under scrutiny. Levine’s gesture has a resilient potency in contemporary economic and artistic climates. The morality of appropriation, copyright law, the efficacy of recycling and a dialectical relationship to ownership – particularly bearing in mind the assimilation of Levine’s work into the canon or the current ecstatic fêting in the museums and auction houses of the work of her direct contemporary Richard Prince – still begs various questions: what does it mean to own an image, how do we receive images and how do they accrue meaning? Reproduced here in the pages of a magazine, without the physical scale and effect of the framed photograph, the image is still unsettling. The direct gaze and resilient aura of the woman in Evans’ photograph are as biting as Levine’s gesture of appropriation, the latter rendered invisible here but without a diminishing of the gesture’s power. To quote Levine: ‘When I started doing this work, I wanted to make a picture which contradicted itself. I wanted to put a picture on top of a picture so that there are times when both pictures disappear and other times when they’re both manifest; that vibration is basically what the work’s about for me – that space in the middle where there’s no picture.’2

Sean Snyder, Korean Central News Agency, Pyongyand, DPRK (2007)

Sean Snyder’s selection and presentation of press images representing the North Korean leader Kim Jong Il are as precise a gesture as Levine’s, although in this instance Snyder’s work details a spillage of meaning. Kim Jong Il, if standing, is usually officially photographed from the waist up, a method that masks his diminutive stature. Here Snyder directs the viewer’s attention downwards to Kim Jong Il’s specially fabricated footwear, which is co-ordinated to his suit to hide the rather substantial platforms built into the shoes themselves. These images, assiduously sourced by the artist, reveal what is usually repressed. Kim Jong Il’s vanity and power are often mythologized as both absurd and chilling. Snyder’s simple picture-editing and rational grid arrangement emphasize the leader’s elaborate image construction and stupid performance of power, but in doing so they also underscore that which is in turn vulnerable, banal and seemingly more ‘real’. Echoes of this spillage of meaning can be found in recent press images of Vladimir Putin with his shirt off – unbound by protocol here is a man with enormous self-regard and an identity built on aggressive power – and of Nicolas Sarkozy’s shoe lifts, particularly when positioned next to Carla Bruni’s elegant bare ankles in modest ballet flats. And then, in sharp contrast, the terrible blouson jackets of Saddam Hussein’s executioners – terrifying because the lack of formal uniform signalled such violent chaos.

Alfred H. Barr Jr. looking at Alexander Calder’s Gibraltar (1936) in 1967

This is an image taken in 1967 of Alfred H. Barr – the New York Museum of Modern Art’s founding director – looking at an Alexander Calder sculpture, Gibraltar (1936). The sculpture is an odd collection of objects positioned on a plinth: a lump of rock, a smooth shelf, what could be a ping-pong ball and two thin upright metal sticks, one supporting a lick of material, perhaps metal or stone. Gibraltar is a wonderful and absurd collision of weight and balance, form and content. Barr confronts the strange shape with a thoughtful half-smile. He appears to be instructing the viewer how to look, searching for and directing meaning while simultaneously posing for the photograph. The sculpture resonates with all the totemic allure of a fetish. The photograph is a performative image of pedagogy and power. There is something both ancient and hilarious witnessed in this symbolic exchange.

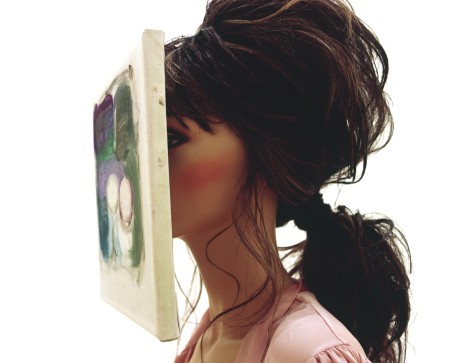

Cathy Wilkes Non-Verbal (2005)

Cathy Wilkes’ installation Non-Verbal (2005) consists of an arrangement of found and made objects including Maclaren prams, Sony televisions, salad bowls, a trough of petrol and partially clothed shop mannequins, their faces obscured by petite Expressionist paintings. Wilkes’ immersive installations always have a palpable neurotic tension best described as conjuring a sense of arrested dynamic. The image here depicts a painting fixed to a mannequin’s head: side-view, full-frontal. There is something brutal and obscene in Wilkes’ confusion of sight lines. An exchange of social relations is made manifest, entailing some kind of refusal that is hard to read. The work appears grotesquely mannered, but the gesture is bluntly precise. This jumping between linguistic registers is emphatic, pointing to either artifice or a heightened awareness. The jangling tone of the objects resonates; the scene has no clearly defined threshold, and, as such, it is experienced as an event. The formal arrangement of Wilkes’ installation has both the crispness and distance of a Social Realist photograph by Walker Evans or Dorothea Lange.3 Wilkes’ assemblage of objects conjures the psychological weirdness of experiencing the inanimate world – the stuff that surrounds us – and the present moment.

Alain Resnais Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

Alain Resnais’ feature film Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) is based on a screenplay by Marguerite Duras. The film is set in postwar Hiroshima, where a French actress, in the city to make a film about peace, embarks on an affair with a Japanese architect. This simple narrative is a vehicle for an allegorical tale of love and desire set against the dynamic of history, the temporality of filmmaking and the difficulties of representation. Remembering is pictured here as a social responsibility, the personal is read through the political and the private act through public resonance. Resnais’ use of a montage of narrative flashbacks, dissolve effect, documentary footage and a doubling motif of a film within a film was as innovative as his, and Duras’, depiction of the postwar mixed-race romance and atomic subject matter. The film still presented here is from the opening sequence of the couple embracing. The bodies fill the frame, putting the viewer immediately at an intimate relation to the narrative. The film then moves seamlessly back and forth from the couple to newsreel footage depicting the destruction and reconstruction of Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bomb. The voice-over speaks of the denial and assertion of representation, of place and event – specifically of Hiroshima – creating a dissonance with the images so emphatically presented. The film creates a tension that is tense-less – past, present and future are suspended in the lived moment. Hiroshima serves as both geographical site and enigmatic signifier. To quote Duras from her screenplay synopsis: ‘Their embrace – so banal, so commonplace – takes place in the one city of the world where it is hardest to imagine it: Hiroshima. Nothing is “given” at Hiroshima. Every gesture, every word, takes on an aura of meaning that transcends its literal meaning.’5

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster Plages (2001)

Two films by Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Rio de Janeiro (2000) and Plages (Beaches, 2001), document life on Brazil’s Copacabana beach. This still from Plages reveals the crowds occupying the beach and boardwalk on New Year’s Eve. Shot from a building high above, the film gently sweeps over the scene. In the film notes Gonzalez-Foerster describes the camera as ‘breathing in time with the waves’.7 She could be describing the waves of sea, people or painted pattern of the boardwalk’s paving stones. The camera circles through fireworks, smoke and explosions, and ‘the atmosphere is at once volcanic, bellicose and festive’.8 The work achieves a simple economy of filmmaking. Gonzalez-Foerster’s films often utilize, to great melancholic effect, the indifferent gaze of a touristic register.9 An attempt is made to define and locate Copacabana, but it is found to be a myth, a fiction and almost impossible to represent as a place. As you watch the swarms of people on the beach, a selection of voice-overs – overlaid as though also in time with the waves, in rhythm with the moving images – recount memories of Copacabana, including a song, an architectural description and a teenage reminiscence. The stories embellish the images with personal narrative and Utopian aspiration. The last voice is that of a fisherman from Copacabana, who states: ‘Copacabana does not exist.’10 Gonzalez-Foerster has said in relation to the invitation to make a project in Brazil and here with reference to Copacabana: ‘I didn’t want to build anything, and I only had visions of things that are either horizontal or go deep. I don’t believe in any verticality. What I like in Rio or in Copacabana is that people are standing on the beach; they don’t sleep or they are not lying [down]. It always looks like a giant meeting or opening and I wanted to go further with that feeling of the dynamic beach.’11 What Gonzalez-Foerster captures in Plages is a sense of continuous movement. There seems to be no beginning or end to the beach or to the film. What is relevant here is how the film represents a field of vision and signals a dispersal of looking.