¡Tenemos Asco!: An Oral History of the Chicano Art Group

Members and affiliates of Asco reflect on the influence of the Los Angeles avant-garde group and the events that inspired its creation

Members and affiliates of Asco reflect on the influence of the Los Angeles avant-garde group and the events that inspired its creation

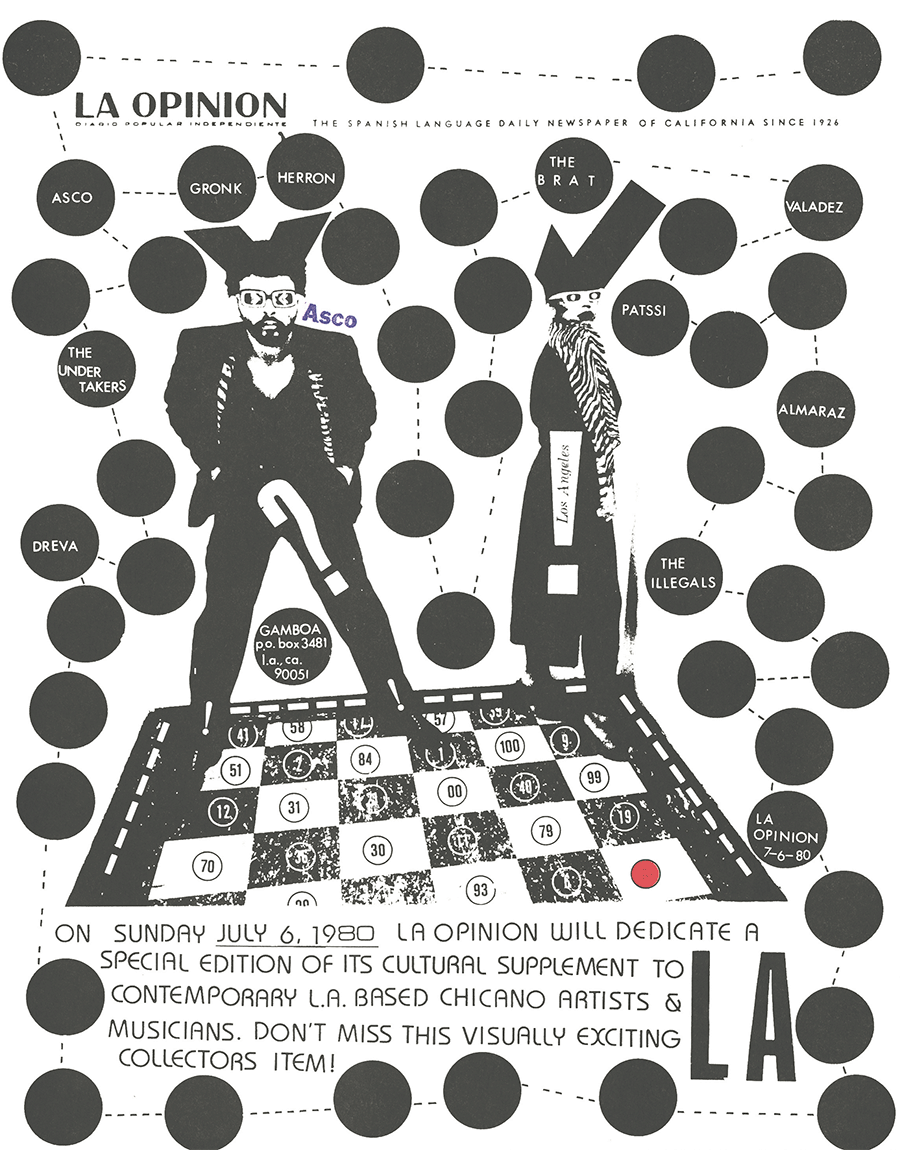

Inspired by the Chicano civil-rights movement and reacting to police violence against people of colour in 1970s and ’80s Los Angeles, members – Harry Gamboa Jr., Willie Herrón, Glugio ‘Gronk’ Nicandro, Patssi Valdez – and affiliates of Asco gravitated towards a distinct ethos and mode of expression that included performance, video, fashion, conceptual art, dance and muralism. However, individuals that participated in Asco events were often orbiting along their own separate realities, as Gamboa points out in this dossier: ‘We were all on different trajectories, following our own pathways.’

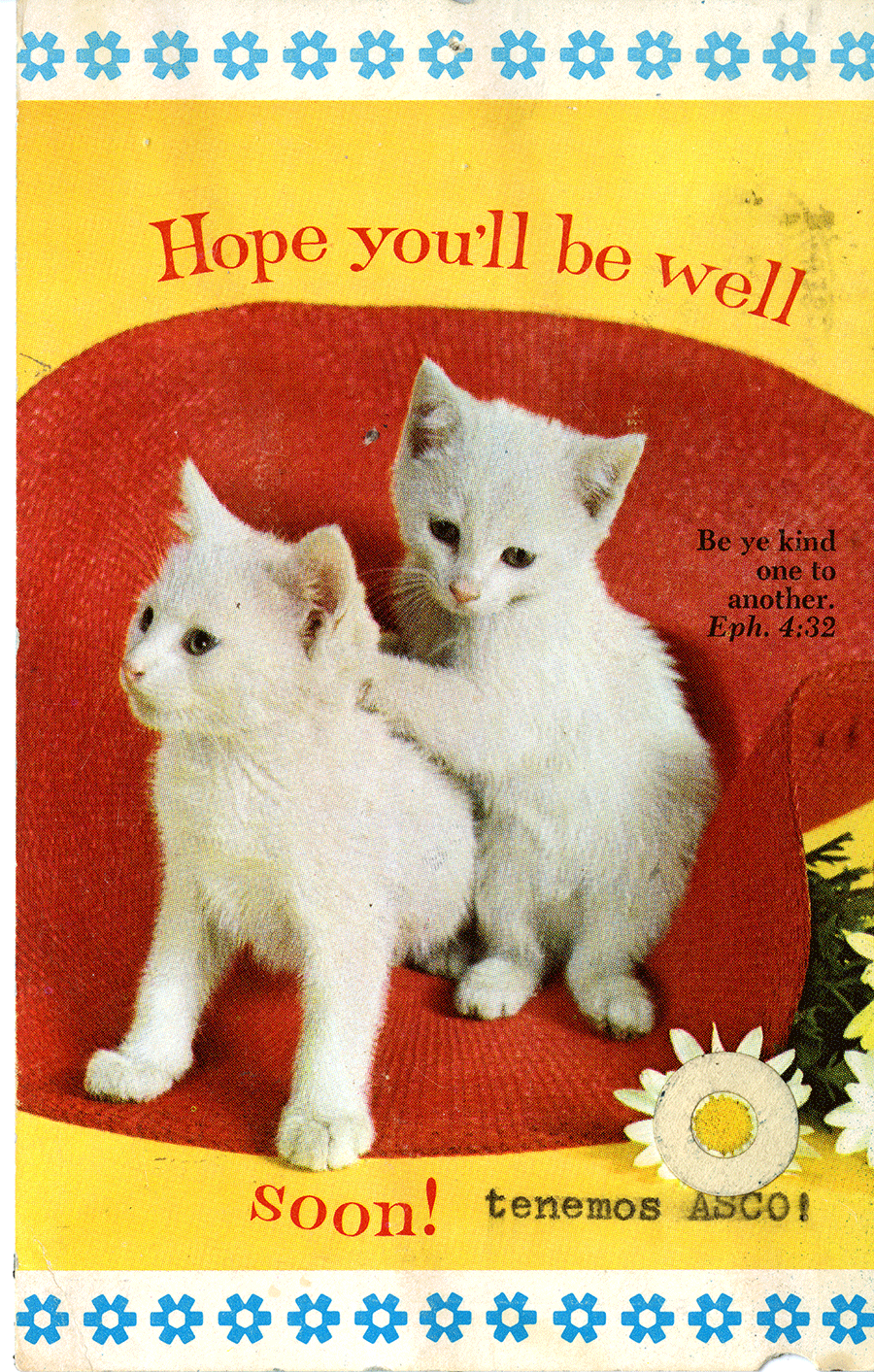

This group of creatives vibrantly converged between the late 1960s and ’80s, making iconic works – such as their ‘No Movie’ series (1973–78) and Instant Mural (1974) – that poignantly addressed the programmatic erasure of Chicano culture in the mainstream media and the religious iconography of the Chicano muralist movement of the time. In this exciting moment, Asco produced a salvo of happenings that resisted all classifications and rules, while providing a space for Chicano artists to be part of their own avant-garde. ‘We Are Disgusted!’ – what the title of this section translates to – captures both the visceral feeling against the violent racism that plagued the city in this moment and the self-affirmation of the group’s subversive, hit-and-run tactics that came to define its creative practice: ‘We Are Asco!’ frieze spoke to Gamboa, Gronk, Herrón and Valdez, as well as Sean Carrillo, Humberto Sandoval and Joey Terrill, to gather their accounts of the group’s layered history and how the spirit of Asco lives on today.

HOW DID IT ALL BEGIN?

Harry Gamboa Jr. I first met Willie [Herrón] and Patssi [Valdez] when we were all students together at Garfield High School in East Los Angeles. I knew them as being two people who could draw. When I was asked to become editor of the leftist magazine Regeneración in 1970, I recruited Willie to help illustrate the magazine. I had also seen one of Gronk’s works, so I sought him out as well, along with another artist, Mundo Meza. Gronk agreed to contribute to the magazine; Meza did not. So, between 1970 and 1971, it was Gronk, Willie and I who worked on the magazine. We would just draw on these boards, talking through the night, and, occasionally, Patssi and Humberto Sandoval – who grew up with Willie – would show up.

Patssi Valdez I joined the group as a founder member in 1972, a couple of years after I graduated from high school. I was already a practicing artist, but I knew Willie and Harry from way before. Willie and I were dating at the time: he was an incredible visual artist at an early age. One funny memory I have of Harry is that my friend, Silvia Delgado, and I were standing in front of school one day and this guy drives by in his Volkswagen and snaps a photo of us. We’re like: ‘Who was that?’ Then, later, in the hallway, the same guy – who turned out to be Harry – comes up and hands us a manila folder and inside were the photographs. I can even vaguely remember what they looked like. I met Gronk later through my younger sister, Karen, who was involved in a play that he had written called Caca-roaches Have No Friends [c.1970]. She asked me if I wanted to come and see what they were doing at Belvedere Park. I said, sure and, before I knew it, I was participating in the performance. Gronk and I had an immediate connection and, from that first meeting, we became inseparable for years.

Glugio ‘Gronk’ Nicandro So, I was doing things in East LA – more conceptual, performance-driven work – then, Willie and I started doing murals together. Well, Willie was the muralist, really; I was more the juvenile delinquent and also the only gay member of Asco. But, in high school, I put on this play [Caca-roaches Have No Friends] in the local park, which I described as a children’s puppet show. A couple of drag queens and a few people from high school participated in the show. After that, I developed a reputation for doing happenings or performance pieces.

Willie Herrón We all met separately when were teenagers in 1969. At the time, I went to a couple of Gronk’s performances, which were held at the local park or in the high-school gymnasium. Patssi was performing on and off with Gronk, as well. I would just spectate but, at the end of the performances, we would hang out and talk. That was the beginning. Harry was dating this girl called Silvia, who lived just up the street from Patssi, so sometimes we would all meet at Sylvia’s house and hang out. Then, little by little, we’d meet at parties, stuff like that.

We never really talked about doing anything collectively until 1971, when we started doing street performances together. Prior to that, I had already teamed up with Harry on Regeneración. I did some spot illustrations, and I think Gronk did too, but we weren’t really working on the magazine together: we were just separately contributing at different times. That evolved into all of us working together in my studio, which was a two-car garage in the alley behind my mum’s house in City Terrace. But, at that point, it was just me, Harry and Gronk. In fact, Patssi wasn’t involved in our first performance, Stations of the Cross [1971], where we carried around this huge cardboard crucifix. She didn’t come in until the following year, when we did Walking Mural [1972] and we walked down Whittier Boulevard on Christmas Eve in different outfits caricaturing religious icons. After that, all four of us started collaborating on performances.

WHY ‘ASCO’?

HGJ The term asco is Spanish for nausea. It also means disgusting, so we used it in a jokey kind of way to vie against the conservative nature of our Mexican/Chicano community, also by dressing in these outrageous outfits and wearing makeup. I walked around with yellow eyebrows forever, and Willie always wore make-up, Gronk, too. We would out-Twiggy Twiggy. It had nothing to do with our sexual preference and more to do with fashion. If I was walking down the street with yellow eyebrows wearing fishnet stockings, someone’s mother would say: ‘Hey, que asco!’

PV We were preparing for an exhibition and working into the wee hours of the night. When we hung the work – some of it was still wet – we looked at it and I don’t remember who actually said it, but we all went: ‘Yuck, this work gives us asco!’ And it did. Then the name seemed to stick.

GN The reaction to what we were doing in our community was generally negative – people would always think it was ugly and distasteful. It was Willie or Harry who came up with the idea of doing a show of our worst works and calling it ‘Asco’. And I just thought: that sounds fitting for an exhibition.

WH Some will say that people called us asco because our work was horrible. But I remember doing collaborative work in the early 1970s with the painter Carlos Bueno, who was affiliated with Sister Karen’s Self Help Graphics [a community arts centre in East LA], which at the time was on Brooklyn Avenue, now known as Cesar Chavez Avenue. In 1973, Carlos and I had an exhibition together there. Shortly afterwards, Sister Karen approached me to do another show. I asked her if I could bring in some of my other partners. This was in 1974 and, by that point, we had already done the Stations of the Cross and Walking Mural. I told Sister Karen that I wanted to do an exhibition of our worst work. She just laughed and said I was crazy. So, I told the guys to pull out everything they didn’t want people to see and suggested we call the show ‘Asco’. Harry and I designed the invitation. We went on a photo shoot. Harry took photos. I took photos. We ended up using one of my photographs of the four of us for the flyer I put together in 1974.

WHAT IS YOUR MOST MEMORABLE ASCO MOMENT?

GN One of the pieces that people still talk about is Spray Paint LACMA [1972]. It’s a photograph of Patssi outside the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, leaning on a wall that has been spray-painted with the names of Asco group members in response to a comment by one of the museum’s curators that Chicanos only make folk art or join gangs. Instant Mural [1974] – in which Patssi and Humberto were duct-taped to the wall – is another. The piece was a reaction to certain things happening in the art world at that moment, but it was also about oppression. For me, that was the concept of the piece: how people are affected by red tape on an almost daily basis, so we can either stay trapped or break free.

For each of us, the work meant something different. It wasn’t that we had one idea or that we were doing this for a specific reason: our practices were quite diverse. Harry photographed many of the pieces, for instance, which allowed others to be participants.

I think the most exciting moments for me were creating the artworks in the series ‘No Movies’ [1973–78], because each had a sense of being a driven, in-your-face performance and, for us, that was the only way to express things. We had to generate our own sense of an art world because people were not going to see us as artists.

PV Instant Mural was a response to the murals painted all over East LA. We decided to create a work that would make a statement but that, as quickly as we’d made it, could be removed from the wall without leaving an eyesore. The idea, for me, was to express how I felt restricted and held back as a woman in our community and society, but how I could then rip through the tape and break free. Given the heavy police surveillance in our community at the time, as in many of our performances, we used what we called hit-and-run tactics, meaning we had to do things quickly so we wouldn’t get busted or harassed by the cops. We had everything ready – what we were going to wear, how we were going to look – then we would jump in the car, find the location, do our performance and, just as quickly, get back in the car and drive away. I remember being horrified at the thought of ever going to jail!

At one point, when I was being taped to the wall, a group of guys drove by in their car and thought I was in trouble, which was sort of hilarious. They shouted: ‘Oh my God, can we help you?’ I told them: ‘No, I’m fine.’ Then I broke through the tape, jumped in the car and we took off.

HGJ Stations of the Cross was pre-Asco but, in some ways, it was our debut performance piece, although I was very much always doing agit-prop activities throughout my youth. Willie had the idea of creating a large crucifix, which he invited us to smear with mud, then we marched it down Whittier Boulevard, wedging it into the doorway of a military recruiting station. We had measured the doorway to make sure that the cross would just fit inside it. The piece was essentially conceptual but, at the same time, it was also useful in making sure that Chicanos wouldn’t be drafted into the Vietnam War at least for one day.

Spray Paint LACMA would probably be recognised by art historians as the first Asco action. The piece emerged from a conversation I had with one of the curators at LACMA, who essentially said some off-putting things about how Chicanos were only in gangs and that they didn’t make art. I mentioned this to Gronk and Willie, then I drove them back to the museum and we decided we were going to graffiti our names on the lower righthand corner of the exterior wall and claim the museum was our first work of art. That evening, Patssi was unable to come with us, so I drove back to East LA, dropped Gronk and Willie off, then drove Patssi back the next day to photograph her. Within a few hours, our spray-paint had been whitewashed.

PV To give a little background: I always wore these super high platform shoes. I mean I literally kept them by the side of my bed for when I got up in the morning, because I didn’t like being short. So, I remember sometimes they would say: ‘Patssi, are you going to be able to run in those shoes?’ And I’d be like: ‘Oh, no, I didn’t bring my tennies!’ Then, Willie was a little bit overprotective, but the police issue at the time was quite frightening: they’d beat up kids at parties and stuff. Anyway, I guess the others decided to go in the middle of the night and spray paint LACMA but left me out of it. So, the next morning, when I talked to Harry, I was pissed. I was like: ‘How dare you? You guys didn’t even have the guts to put my name on the damn wall!’ So, they said: ‘Okay, let’s go right now.’ I got in the car and we zoomed over to LACMA that morning, and that’s when Harry photographed me in front of Spray Paint LACMA.

WH I don’t remember Gronk going to LACMA. Somehow, I can’t grasp in my mind whether he was with us that day. Anyway, we tagged the museum wall and then we left. We also plastered wheat-paste posters at the entrance on the cement ground. Hardly anybody knows that happened. I don’t even think there’s documentation of it. I do remember, however, Patssi being very pissed that she wasn’t there.

Humberto Sandoval I was involved in a lot of different videos and street performances that Asco did, but there are two that I remember fondly. The first is Sr. Tereshkova [1974], a film that I wrote and directed. Harry filmed it and Gronk, Willie and Patssi were in it. It was about a shopkeeper who has these dreams with a mannequin. There’s a great picture of all us from that shoot.

The second is the performance Void and Vain [1983]. There was an art centre in the Mission District of San Francisco called Galería de la Raza. And we had a rough ride up there because there was a whole lot of liquor and possibly some hallucinogens, but we ended up in San Francisco in a state. Harry had written this play with two characters talking nonsense. One of us was Void and the other was Vain. That was one of the only performances that Harry got involved with, I think. He was always either filming or photographing, of course.

Joey Terrill I don’t know if this counts as an Asco moment but, when I did the second issue of Homeboy Beautiful – a queer Chicano magazine I produced between 1978 and ’79 – I posed for the cover in front of Willie’s mural The Wall that Cracked Open [1972] in East LA. I was wearing my East LA leather jacket and carrying a fake, black, round, cartoon bomb. So, I was posing while my friend Rick was taking a couple of pictures. The mural was in an alley and some good-looking Latino comes out of a garage and says: ‘What are you doing here?’ And I reply: ‘It’s for the cover of an art magazine.’ And he asks: ‘Are you going to give credit to the muralist?’ And I say: ‘Of course, this is a mural by Willie Herrón.’ And he says: ‘Hi, I’m Willie Herrón.’

Sean Carrillo I know this is terrible to admit but, at that time, I loved reading People magazine [1974–ongoing], which was new. And, one time, I found a subscription card in it that said: ‘You’re invited to be a charter member of a new magazine called New West.’ New West [1976–81] had the exact same logo as New York Magazine and was published by the same people, who were trying to launch a West Coast version. So, 16-year-old me signed up for New West and, in one early issue of the magazine, I’m flipping through and I see these pictures and I’m just like: ‘What the fuck: there’s a guy taping a woman to a wall!’ And they do murals that don’t look like anything else I’ve ever seen. But then, because I grew up in Boyle Heights, I’m like: ‘Wait a minute, I know that mural.’ That’s Willie and Gronk’s Black and White Mural [1979].

WHAT INSPIRED YOU?

PV In part, we were responding to the narrow definition of what was considered Chicano art at the time. In my youth, I found it very frustrating not to be heard or taken seriously as a young woman. I was so sick and tired of the sexual harassment I had to deal with on a daily basis. I was just mad about it. My influences were really about my community, my culture and the things around me at the time. But I also was influenced by fashion: I remember hanging out at this magazine stand in Hollywood and looking at all the international issues of Vogue. The other thing was the rock scene: music, for me, was a big influence on what I was doing. I also loved silent-era, black and white movies: the way an actress like Theda Bara could seduce you into a film just with her eyes. But, ultimately, I wanted to make art about what was around me, rather than be influenced by what other artists were doing.

GN I was influenced by so many people, particularly Jean Genet, John Rechy and other gay writers of that period. The Stonewall uprising of 1969 resulted in a lot of information becoming more accessible but, even before then, the numerous Latino and Black gay bars in LA were a great font of knowledge – just another way for me to investigate my ideas.

I was brought up not only with Hollywood films but with Mexican cinema, too, which definitely had an impact on my work. My friendship with the East LA poet and writer Marisela Norte grew from our shared love of film: whenever we spoke, we would end up talking about movies, and not necessarily just the iconic ones! The Vietnam War was also still very much on the agenda in the early 1970s, and the Latino population was getting drafted: people we knew were coming back in body bags. So, we did experience the genuine horror of our generation being wiped out. That was certainly also a motivation for many of the pieces we did.

HGJ I was heavily influenced by my involvement in activism prior to Asco. After the Chicano Moratorium in 1970 – one of the largest Mexican-American demonstrations against the Vietnam War – the cops were really framing Chicanos as being a danger to society, putting us all on a list. I would always have with me in my car maybe five or six changes of clothes, depending on where I was going, just to evade the cops. The feeling was that, because we were Chicanos, we were never allowed to hang out at all, period. But you could go somewhere and hang out for two minutes and, for those two minutes, that was the coolest place to be in all of LA.

So, my concept with photography was that you only had to be in any spot for a thousandth of a second to make it cool – as long as you took the picture properly. I found out later that the cinematic stock used for major motion pictures was readily available to the public, and there were two or three outlets in Hollywood that would sell it as slide film. So, most of the early Asco imagery was shot on that material, which gave it its cinematic quality. Of course, that look was intentional because the idea was to challenge all the negative stereotypes Hollywood generates about Mexican Americans, disallowing them to participate in the system at all. With the exception of actor-director Anthony Quinn, and a handful of others, it was just too prohibitive and time-consuming to try to make a movie as a Mexican American. That was precisely the inspiration behind the ‘No Movies’ series.

WH Mostly, for me, my inspiration came from being depressed as a child. Growing up, my family ran a bakery, and I missed a lot of school because we were nocturnal. We baked most of the bread at night so it could be sold fresh at six, seven o’clock in the morning. Many times, as a child, I was just too tired to even go to school. And there was a lot that I was feeling. Then, going into my teens, seeing both of my brothers get involved in the cholo gang lifestyle, it was difficult. I always felt connected to being a visual artist and playing music, which I had done since I was a kid. In 1962, I got my first organ and started teaching myself. I wasn’t formally trained in art or in music – I just did it on my own – but that was where I got my peace of mind, an outlet for my depression.

HOW DID IT END?

HGJ Asco was a group of competing entities. The way I describe it is that, when we initially met, we were all on different trajectories, following our own pathways. But, between 1972 and 1987, there was a moment of intersect when we all came together to interact, experiment and participate in projects, picking up a little bit of stardust along the way.

WH In 1979, I started a band called Los Illegals and started concentrating on that. By the 1980s, Patssi had left to do her own thing, while Harry and Gronk branched off to start writing and performing together. That’s when they brought in Harry’s sisters, Diane and Linda, along with some of their friends.

PV Willie and I broke up, then I left to go to college in 1982. By that point, I wasn’t sure what was going on with the group, but my understanding was that Harry and Gronk continued. I called it Asco 2.0. I don’t think it was ever the same. That’s when Sean Carrillo, Therese Covarrubias and others came along. But, in an odd way, Asco continues to this day in spirit, and now it’s inspiring other young people. So, I don’t think Asco has ever died.

GN There’s another generation now that will take up where Asco left off. I always hoped I’d see signs of that kind of regeneration and I do: there are a lot of young artists out there doing performance who are grateful that we were around because we didn’t just do political slogan art. Asco had ideas that lasted: it was a rebellion that never really ended.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 224 with the headline ‘¡Tenemos Asco!’.

Main image: Asco, Patssi Valdez, Willie Herrón and Gronk in Walking Mural, 1972, photograph. Courtesy: © Harry Gamboa Jr.