Then & Now

British art and the 1990s

British art and the 1990s

Gallery Connections was an artist’s project by the late Angus Fairhurst published in the pilot issue of frieze in 1991. It was simple, ingenious mischief: a pair of telephone receivers were placed next to each other, and the numbers of two commercial galleries in London were simultaneously dialled. ‘Hello, Interim Art.’ ‘Hello, Anthony Reynolds Gallery.’ ‘Hello?’ ‘Hello?’ ‘Can I help you?’ ‘Sorry?’ ‘I was just saying to someone it happened to me on Friday with Annely Juda …’ ‘We’ve had it happening with Nicholas Logsdail at the Lisson …’ Each gallery thought the other was calling them. Some blamed a technical fault. Others worried they’d been bugged by the Inland Revenue.

Fairhurst hit two museums and ten London galleries with his calls. Ten was around the total number of commercial galleries dealing in contemporary art in London at the start of the 1990s. Today there are hundreds. Gallery Connections was made before everyone used mobile phones and email, before Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and the airless feed of Contemporary Art Daily. It was made in the final decade in which art was created and circulated by primarily analogue means. Gallery Connections was a closed-circuit conversation that in 1991 may have been borne out of play, but now reads like futurology; a thumbnail sketch of today’s integrated business-to-business superstructure of dealerships, advisories, auction houses, art fairs, private collections and museums.

I moved to London in 1999. St Paul’s Cathedral was black with grime and Tate Modern was a work-in-progress. In the West End, there were must-see galleries on Cork Street; Soho was a place where you could still find after-hours bars patronized by sozzled old roués who claimed to have known Francis Bacon. To the east, Shoreditch was seemingly deserted at weekends, yet to suffer death-by-gentrification. Spitalfields had not been sanitized by chain restaurants. Visiting art tourists rarely ventured south of the river; for them, Peckham was another country.

But it was clear I had arrived at the tail end of something. I remember one curator saying – his words slurring as more free wine was poured into his glass – ‘I loathe frieze magazine. It’s all just articles about Tracey Emin and Vivienne Westwood.’ This was in 2000. It had been years since the magazine had published anything on Emin but, at that point, frieze, for some, still stood for young British art in the 1990s, the decade that caused your throbbing cultural hangover. The mockney accented, full-English-breakfast caricature was Damien Hirst gurning in front of his shark and Emin blotto on BBC2’s The Late Show. It was the tabloids fuming over the Turner Prize, and Marxists warning about Charles Saatchi and one-liner advertising art.

I admit to nostalgia for the 1990s because I was a teenager for the first six of them, and then at art school. To someone growing up outside of London, art looked like part of the broader media-scape – interchangeable with hearing Tricky on the radio and watching Alan Partridge on TV – and it’s crucial to understand the compression effect that the pre-Internet media had on the reception of British art in that decade. National newspapers, radio and television (just four channels until 1997) were transfixed by the yBas and the Turner Prize, constructing a London-centric perspective that distorted the picture. Anyone following criticism within the uk art scene at the time would find plurality, divisiveness and argument, from the polemical scepticism of Variant, published out of Glasgow, and London’s Mute, to the conflicting positions of theorists collected in books such as Occupational Hazard: Critical Writing on Recent British Art (1998). frieze offered a cross-cultural perspective, bringing design, cinema and music into the conversation. There were artists and writers, myself included, who were equally as interested in what The Face was covering as they were in October, because it seemed a much more realistic way of thinking about art than in specialist isolation. The flipside to the country’s narrow-cast media was adventurous television programming: I saw Derek Jarman movies on Channel 4, as well as films by Kenneth Anger, Bruce Conner and the Quay Brothers on the Midnight Underground series in 1993, and video work by Mark Wallinger and Gillian Wearing on BBC2’s Expanding Pictures in 1996.

Yet, by the end of the 1990s, much of the contemporary British art I’d initially felt excited about at art school a few years earlier looked embarrassing; weightless, brash, parochial. The decade was too drunk on its own success to notice being instrumentalized by New Labour: slap a Union Jack sticker on the ‘creative industries’ and put Blur on the jukebox, Tony’s getting the next round of lagers in!

So, if the last 13 years have been quietly spent trying to create some distance from British art of the 1990s – attempting to be altogether more circumspect, critical, internationally minded and media coy – why bother with it now? Because lately, it’s been hard to avoid – especially that from London. Last year, Wearing was given a retrospective at the Whitechapel Gallery, London, and the long view was taken on Hirst’s work at Tate Modern. In September, a retrospective opened at the Whitechapel of the work of Sarah Lucas, who was also included in Massimiliano Gioni’s exhibition ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’ for the 55th Venice Biennale. Jeremy Deller represented Britain at Venice this year, and in 2012 he was the subject of a survey exhibition at London’s Hayward Gallery, alongside a solo show of David Shrigley, which included much of his work from the 1990s. Also last year, the Art Institute of Chicago organized a major exhibition of the work of Steve McQueen, which toured to Schaulager, Basel, in June. The early work of Lucas, Wearing, Steven Pippin and Wolfgang Tillmans was included in ‘NYC 1993’ at the New Museum, New York, earlier this year, and a small survey of Gary Hume’s paintings was shown at Tate Britain over the summer. MOT Gallery, London, opened 2013 with ‘The Banquet Years’, a look at the work of artist collective BANK, and a few months later Paul Stolper Gallery, London, staged ‘Factual Nonsense: The Art and Death of Joshua Compston’, which focused on the activities of a now almost forgotten yet influential figure who died aged 25 in 1996. (The exhibition accompanied a book of the same title by Darren Coffield.) In March, Prestel published Growing Up: The Young British Artists at 50 by Jeremy Cooper. The ICA in London staged the exhibition ‘A Journey through London Subculture: 1980s to Now’, placing 1990s British art in the city’s historical underground lineage. July marked another milestone: 25 years since ‘Freeze’, the 1988 exhibition curated by Hirst in an empty London Port Authority building in Docklands that was to become the creation-myth show for the yBa generation.

How does the period look today? Scanning the list of names being given the retrospective wax and polish, the answer should be: ‘It depends on whose 1990s you’re talking about.’ Does 1990s British art mean those embalmed as yBas: Jake & Dinos Chapman, Matt Collishaw, Emin, Fairhurst, Anya Gallaccio, Hirst, Hume, Michael Landy, Lucas, Chris Ofili, Fiona Rae, Georgina Starr, Sam Taylor-Wood, Gavin Turk, Wearing, Jane and Louise Wilson? If so, that doesn’t account for artists of distinctly different stripes. A back-of-an-envelope list might include: BANK, Fiona Banner, Christine Borland, Martin Boyce, Glenn Brown, Angela Bulloch, Billy Childish, Adam Chodzko, Martin Creed, Peter Doig, Tom Gidley, Liam Gillick, Douglas Gordon, Jaki Irvine, Jim Lambie, Hilary Lloyd, Christina Mackie, McQueen, Paul Noble, Simon Periton, Ross Sinclair, Bob & Roberta Smith, Wallinger, Rachel Whiteread. What of those associated more with the 2000s but who made an early mark in the 1990s: Tacita Dean, Deller, Mark Leckey, Simon Martin, Mike Nelson, Elizabeth Price, Tillmans, Rebecca Warren? Or those busy working before the 1990s claimed them: Willie Doherty, say, or Julian Opie, Cornelia Parker and Cerith Wyn Evans?

The period was cacophonously multi-vocal, contradicting the still-dominant media fable that describes one tiny clique behaving badly, cash-rich courtesy of Saatchi and Jay Jopling. But we’ve no clear sight lines back to that decade. Crowding the view is an international art industry the like of which makes even the most trenchant critiques of 1990s art – Simon Ford’s 1996 Art Monthly essay ‘Myth Making’ for example, or the book High Art Lite (1999) by Julian Stallabrass – seem almost quaint. These critics brought analytical anger to the broader media phenomenon of 1990s British art – seeing it as dumb, commodified, self-celebratory – but a much bigger art industry superstructure was being constructed quicker than their critiques could dismantle it.

Imagine fewer galleries, fewer museums, fewer biennials, fewer curators, fewer art fairs. (Yes, the history of this magazine is implicated in the growth of the art industry, but I’ll save that for my memoirs.) Imagine slower digestion of young artists by the bigger art system. The UK was a country in which one collector – Saatchi, j’accuse – could grossly distort the market. (Anyone remember ‘New Neurotic Realism’, his laughable attempt to manufacture a new movement in 1998?) A small number of galleries – Cabinet, Sadie Coles, Lisson, Victoria Miro, Maureen Paley (then Interim Art), Robert Prime, Anthony Reynolds, Karsten Schubert, White Cube – all played significant roles in recalibrating the London scene. There were curators, certainly, but their voices did not dominate the room, and cultural middle management was not the popular choice that it is today for those wanting a career in the arts. (The Royal College of Art curating course, for example, which was established in 1992, was still called ‘Visual Arts Administration’ up until the early 2000s.) The art world was altogether less obsessed with its own cybernetics.

As the standard narrative has it, at the start of the decade the uk was an art backwater mired in muddy ‘London School’ painting, dour figurative art from Glasgow, 1980s ‘New British Sculpture’ and arguments over whatever Art & Language were arguing over in 1972. Change came with ‘Freeze’, followed by ‘East Country Yard Show’, curated by Lucas and Henry Bond at South Dock, London, and ‘Modern Medicine’ and ‘Gambler’ (all 1990) at Building One – a vast warehouse in Bermondsey – both curated by Carl Freedman and Billee Sellman. Hirst’s cow’s head and insect-o-cutor sculpture, A Thousand Years, also made that year, was shown in ‘Modern Medicine’. Strikingly cold, corporate-looking, with added stench of rot, it was one of Hirst’s last works that would be of any value beyond financial. These warehouse shows would become emblematic for some of us who were students in 1995; I barely knew what was exhibited in them, but the let’s-just-do-the-show-right-here ethos was potent and attractive.

As the recession of the early 1990s started to bite, it was artist-run spaces that would assume a more important role and, crucially, London was never the whole story. Catalyst Arts in Belfast; the Collective and New 57 in Edinburgh; Transmission, Glasgow; The International 3, Manchester; Locus+ in Newcastle-upon-Tyne; and London organizations including City Racing, Cubitt, Matt’s, Milch, Infanta of Castile and Nosepaint (later Beaconsfield) were crucial to community, conversation and exhibition opportunities, despite criticism from some quarters that they acted as ‘labs’ for the commercial sector. Accounts of the time suggest networks more characterized by artist-to-artist relationships than today’s artist-to-curator or curator-to-curator ones. The book City Racing: The Life and Times of an Artist-Run Gallery (2002), for instance, devotes an entire page to explaining how the artist Gareth Jones connected a myriad of London people and spaces together circa 1992. BANK are perhaps best remembered for their satirical newspaper, The Bank, which poked fun at the hypocrisies of London’s 1990s art scene. The group – orbiting around core members Simon Bedwell, John Russell and Milly Thompson – wound down in 2003, but had been critical and outspoken in ways that today’s professionalized yet precarious system inhibits. Throughout the decade, BANK organized group shows – such as ‘Zombie Golf’ (1995) and ‘Stop short-changing us. Popular culture is for idiots. We believe in art!’ (1998) – that involved a notably wide range of their peers. Their activities were as generous as they were spiky.

City Racing showed a significant number of women artists until it closed in 1998; it gave Lucas and Wearing their first solo shows (respectively, ‘Penis Nailed to a Board’ in 1992 and ‘I’m Desperate’ in 1993). Cross-country conversations were enabled by these initiatives too: for instance, Transmission and City Racing exchanged exhibitions in 1992. Connections outside the uk were also routed through artists, such as Bulloch and Gillick, giving the lie to the idea that British art was a wholly parochial phenomenon. Quoted in City Racing, Gillick recalls being ‘extremely negative about the British situation, seeing it as obsessed with formalism, hard work and idiot-savantness’. Neil Mulholland, in his book The Cultural Devolution (2003), points out that ‘Scottish artist initiatives in the early 1990s tended to look further afield than the UK’. He cites Ross Sinclair, writing in 1991: ‘Although London will always have a strong pull, there exists a valuable and potentially more reciprocal relationship with the European context.’

This being Britain, class was inseparable from art. (Where else would a band such as Pulp be able to have a hit single in 1995 with ‘Common People’, a song about a rich girl slumming it at Central St Martin’s College of Art?) Artists who came of age in the 1990s were amongst the last generation to enjoy free higher education. The 1944 Education Act had opened the doors of art schools to those from lower-income backgrounds, legislation that was to have a major impact on the kind of art (and pop music) made in Britain, from early 1960s Pop art through to art of the 1990s. Class solidarity, and upward and downward mobility – through professional success or class drag – was a topic for work and a target of criticism, sometimes both. The range of economic backgrounds represented in British contemporary art was perhaps wider back then. Recession, cuts, the introduction of higher university fees and a Tory party ideologically bent on marginalizing arts education, are today closing the doors to working-class students.

Lately, there has been a revival of interest amongst uk artists in early British Modernism – traditionally regarded as the dowdy cousin to sexy and urbane European and us vanguards, yet often imbued with rural, occult or Utopian energies. In the 1990s, it seemed that more recent British art histories, under the influence of German painting and us Pop and Conceptual art, were pressing everyone’s buttons. Art & Language were an important antecedent to the work of BANK, for instance. For a number of artists, Gilbert & George – as well as being early artist colonizers of the capital’s East End – provided a model of art-making that combined video, photography, performance and a wicked sense of humour. London School artists such as Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud and Leon Kossoff – canonized by the entirely male 1981 ‘A New Spirit in Painting’ show at the Royal Academy – were sitting ducks for figurative painters such as Brown, Doig, Ofili and Nicola Tyson. Yet Modernism was never too far away; the boozy Soho demi-monde that painters such as Bacon represented provided a romantic lifestyle model for a certain London set.

Something of the mystic British modern seems to have crept into Lucas’s work in recent years. Her ‘Penetralia’ series from 2008, and her ‘nuds’ (2009–ongoing) look equal parts Barbara Hepworth sculpture, Hans Bellmer dolls and Neolithic totems: rounded forms that echo the shapes of ancient burial mounds; phallic stone and wood assemblages that might be votive props for a pagan rite. The stuffed tights and stretched underwear of ‘nuds’ might not look out of place in a Paul Nash painting, such as An Event on the Downs (1934–5); at her solo show in Mexico City last year they certainly resonated with the 1,000-year-old votive items and figurines of Aztec gods at the Museo Anahuacalli – a dark pyramid-shaped building originally designed as a mausoleum for Diego Rivera, which today houses thousands of pre-Hispanic relics. Her sculpture still press-gangs elements from prosaic, urban sources, but now seems animistic; as if one of the ‘nuds’ might suddenly jump off its coat-rack, or the drunk, vulnerable flop of one of her ‘Bunny’ figures (1997) might twitch to life and ask you to dance. Lucas’s casual formalism is bawdy, materially multivalent and feminist in ways that underscore the deep conservatism in neo-formalist work being created by artists much younger than her – the strains of monochrome and geometric abstraction that clutter galleries from Los Angeles to Moscow. Another form of British occult modern can be seen in Chodzko’s earliest projects. Like behavioural experiments to probe the public sphere, he placed classified ads selling photographs of poltergeists or asking for God look-a-likes, and started a campaign to try and reassemble the cast of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s 1975 movie Salò. Then there were the blood-red resin teardrop sculptures (‘Secretors’, 1993–6), like horror-film props, one of which mysteriously appeared on ITV’s News at Ten in 1994, seeping from a bookshelf behind Gordon Brown, who was then Shadow Chancellor.

It is easy to forget how many more women artists began to show regularly in the 1990s, given that gender representation in today’s art world is as antediluvian as ever. Yet one accusation thrown around was that 1990s art was blithely apolitical. Charges focused on its platitudinous humanism – Hirst’s Big Themes of life, death and religion – or solipsistic individualism: Taylor-Wood’s panoramic photos depicting middle-class psychodramas, Emin’s confessionals addressing rape and abortion, topics that none of the politely intellectual neo-conceptualist artists of that period would touch. Particular ire was directed at artists for being crypto-Thatcherite in their entrepreneurialism (those early warehouse shows were often sponsored), or association with Saatchi whose advertising campaigns for the Conservative party in the 1980s were instrumental in helping Thatcher remain in power. Compare and contrast with art post-9/11, post-2008 crash, post-Occupy, post-Arab Spring and it seems less engaged, but it’s too reductive to rag on 1990s British art for not wearing its anti-Criminal Justice Bill badges proudly enough. Visual art’s relationship to aids activism and identity politics was arguably more of a US than a UK phenomenon. In Britain these issues were played out more visibly in art house cinema: by gay artist-filmmakers such as Jarman and Stuart Marshall, for instance, or in Isaac Julien’s Young Soul Rebels (1991), Ngozi Onwurah’s Welcome II the Terrordome (1994) and the work of Black Audio Film Collective. Artists found themselves caught up in activist causes but did not make it part of their work; in the mid-1990s, some of those involved in City Racing helped grassroots opposition to the building of the M11 link road through east London. ‘Protest and Survive’, a survey of British political art curated by Noble and Matthew Higgs at the Whitechapel in 2000, highlighted attitudes we long suspected were there, and the subsequent decade would see artists make more demonstrative gestures towards politics. Wearing’s photographs and videos tapped documentary and reality TV for inspiration; successfully or not, she attempted to create a commentary on class. Since 1994, Sinclair’s ‘Real Life’ project has used painting, performance, sculpture, video and writing to conduct a sustained conversation about collective political ideals, especially in relation to Scottish identity. In 2001, Landy staged Break Down, in which he systematically catalogued, then destroyed, all his possessions; 45,000 visitors came to watch him. That same year, Deller organized a re-enactment of the Battle of Orgreave, an infamously violent running battle between police and picketing miners during the 1984 Miners’ Strike. In 2007, Wallinger – whose 1990s work had skirted around questions of ‘Britishness’, class and institutionalized religion – made the blunt State Britain for Tate Britain; a replica of Brian Haw’s anti-Iraq War encampment outside the Houses of Parliament. With his video The Pickers (2009), Chodzko laced stories of migrant Romanian strawberry pickers working in the UK today with archive footage of migrant hop-pickers in 1940s Britain.

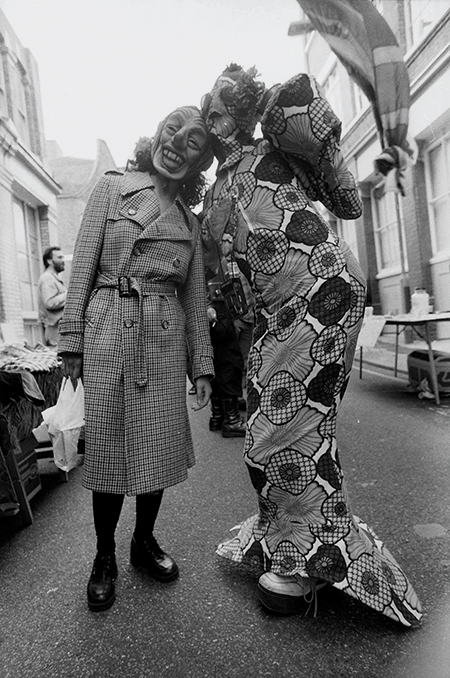

The 1990s saw an unapologetic, often troubling, emphasis on British national culture. Artists weren’t exempt from this, and perhaps one of the more curious characteristics of that decade was how much it embraced local vernaculars. Some retreated inwards to Britain for influence, away from Europe and the US, asserting a new insularity alongside British pop music and cinema. ‘A Fete Worse than Death’, organized by the mercurial Compston, was a street fair held in Shoreditch in 1993, an alternative take on the traditional British garden fête. Fairhurst and Hirst dressed as clowns and sold spin paintings for a quid each. (Leigh Bowery did their make-up.) Hume dressed as a Mexican bandit selling tequila and Turk set up a game of ‘bash the rat’. Looking back at ‘A Fete Worse than Death’, noting the neo-Victorian aesthetic Compston used for projects under his Factual Nonsense moniker, it’s tempting to read these as early signposts to today’s twee, commercialized nostalgia for a Britain that never was: ‘Keep Calm and Carry On’ posters; Jamie Oliver’s traditional British grub; bland high-street clothing chains like Jack Wills marketed as old-school gentleman’s outfitters; the cartoonish 2012 Olympic opening ceremony – all Mary Poppins, men in bowler hats and songs by The Who. In art it might persist through the lens of Deller and Alan Kane’s ‘Folk Archive’: photographs, videos, paintings, sculptures and objects championing contemporary folk art, running the whole gamut from barrel-rolling competitions to art from prisons. A thoughtful project, but a complex and thorny subject.

All of which brings us back to class; back to arguments over who gets to speak for whom, especially where art-market money is concerned. British art can be depressingly provincial, impossible to fully parse for those who didn’t grow up with certain TV shows or holidays in miserably wet seaside towns. Yet for 1990s British artists, speaking in the vernacular was arguably just demonstrating lessons adopted from us Pop art. Pop as in popular, accessible, shared by many; or subcultural, for those tuned in. But also Pop as in big business, capitalistic, exploitative. Pop has run through postwar British art with notable fluidity – Tillmans’s easy oscillation from commercial magazine work to more personal photographic subject matter, is exemplary in this regard – and the 1990s consolidated the fact that, for a generation of British artists born in the 1960s and ’70s, Pop was mother’s milk. Artists weren’t the only ones using derelict warehouses in 1988; it was the year acid house broke, a deeper culture-quake than ‘Freeze’.

The mutiplicity of pop is what appealed to me when I first discovered it in my late teens. It’s why I could never – no matter how compelling other criticisms might have been – wholly buy the argument that the pop references in 1990s British art were cynical and populist. Pop was not a discrete category to be ‘dealt with’ or ‘appropriated’, handled with bleach-white gloves of criticality, any more than humour was. If 1990s art in the uk has left a legacy, it is not just in cautionary tales of celebrity and economics. It lies in lessons about self-organized community and collective activity, however fractious, and in the importance of irreverence towards art’s institutions and pieties.

Not so long ago, I was introduced to a young staffer from a prominent literary review. I told him I worked in contemporary art. ‘That’s not serious culture,’ he sneered. ‘That’s just diamond skulls and Saatchi and those “Sensation” artists, isn’t it?’ ‘No,’ I replied, ‘it’s not.’