‘There Was Great Purity in American Art. I Wanted to Insult It’: Going Rogue With Peter Saul

As the artist has his major retrospective at Les Abattoirs, Toulouse, he speaks about his art historical influences and pet peeves

As the artist has his major retrospective at Les Abattoirs, Toulouse, he speaks about his art historical influences and pet peeves

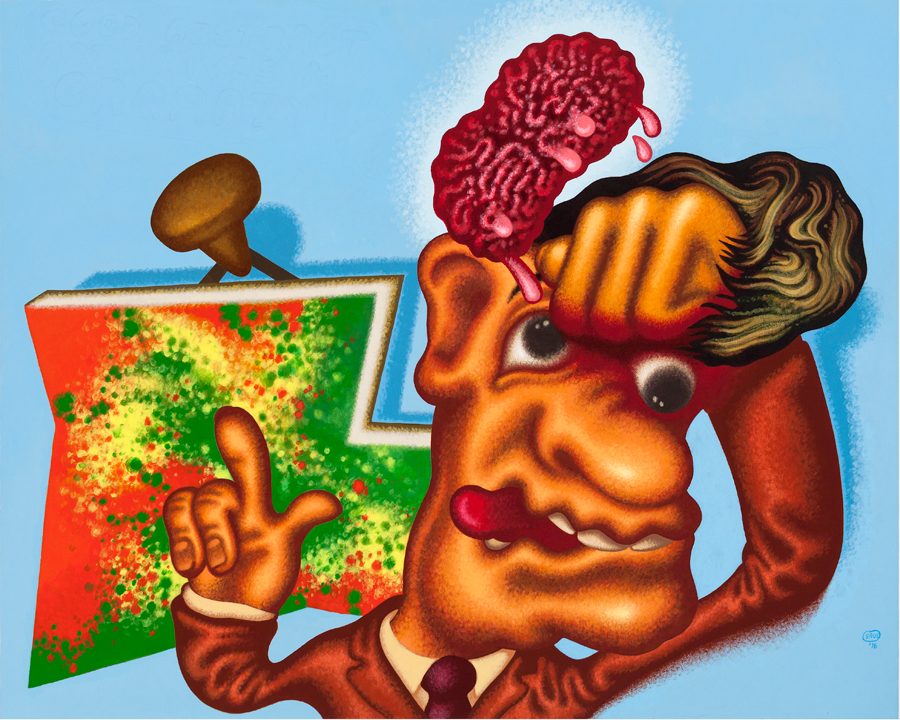

Among the ducks, dogs, boxers and presidents in Peter Saul’s paintings, there’s room for an art critic or two. One is punching himself in the face. Blood oozes, an eyeball pops. On his fists are tags saying ‘Self Expression’ and ‘Formalism’. He’s beating himself up with his own critical terms. In Art Appreciation (2016), a critic points to a painting, scratching his head. Meanwhile, his entire brain squeezes out through the top of his eyelid. Saul is a complex painter, but not a subtle one.

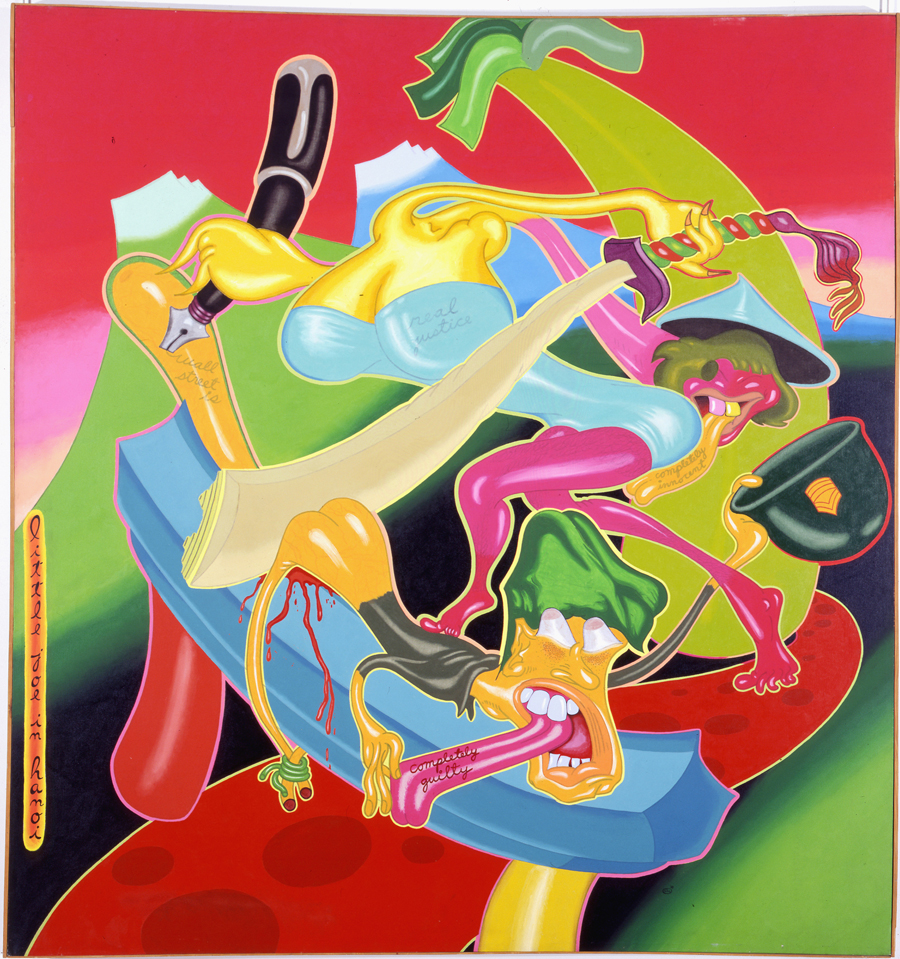

If Saul enacts such violence upon his critics, how are we to approach and appreciate his art? He’s made a craft of misbehaving, a point of skirting the status quo. Beginning his career in 1950s San Francisco, he migrated to Europe in the 1960s. Gradually, he placed himself in opposition to the era’s critical darling, abstract expressionism. Backed by Clement Greenberg, abstract expressionsim relinquished representation in favour of promoting the formal purity of the art medium. Greenberg saw the movement as the antidote to a stagnant culture, fed from the mindless repetition of the same subjects. For him, the abstract was a kind of secular sublime.

But for Saul it’s silliness. The abstract expressionists were the first people he wanted to ‘insult’. He found that being insulting was a productive avenue for picture-making. And making pictures is what matters most to Saul. During our conversation, he comes up with ideas for two new paintings, and is visibly excited to get back to the studio. Controversy comes easily to him, and yet he’s a painter of strange purity himself, believing in the craft of the thing even as he violently dismantles its critical apparatus.

He’s anti-establishment without being anti-intellectual, and a provocative meme-speaker without being a troll. Subject/object, self/other, free speech/safe space: somehow they’re all there in the paintings, together. In times when such concepts are undergoing turbulent redefinition, it’s possible that Peter Saul’s natural art of misdemeanour cuts a fine and easy path to some otherwise unutterable ‘answer’.

Adam Heardman met with Peter Saul at the opening of ‘Pop, Funk, Bad Painting and More’ at Les Abattoirs, Toulouse.

Adam Heardman: I’d like to start by asking about the beginning of your career in Holland and France. How did that influence the way you painted America?

Peter Saul: Well, my thinking then, in 1958 or ’59, would be that I was insulting American art by putting in ‘subjects’. There was a great feeling of purity in American art, and I thought that was very silly. I wanted to insult it. I think I’m afraid of being overlooked. If I’m part of some sort of intellectual majority, I fear I won’t be paid any attention to. So I feel that if I’m an outsider I actually do myself some good.

AH: Is there anyone or any thing that you feel you can’t paint?

PS: I promised various people not to paint certain things. I’m 85, and I’ve insulted so many people. There’s no reason to dig around and find things that people find really offensive. I’m going to deal with women as a subject next, and that will be a problem, right there.

AH: Have you any idea how you might approach the subject?

PS: Sure! One of the first paintings is: a guy approaches a woman at her desk, unzips his pants, flops out his weiner. At the same moment she takes a 2B pencil and thrusts it through his head and says, ‘ I told you no. One more time!’, something like that. I haven’t designed the picture yet. Probably he’s got short legs and a long zipper, you know what I mean? The other thing I did was Van Gogh cutting off his ear. I can do that two more times. The next time he cuts off much more ear. Side of the head. Finito. And, let’s see, the third time it’s probably even worse. Everything goes. Just a pair of lips left.

AH: I guess the fact I just laughed answers my next question. Is violence funny?

PS: Unfortunately. I laugh at almost everything. I probably shouldn’t, but I do. That’s life. I discovered from teaching that most people don’t agree with me on this kind of thing. They don’t laugh at things that are inappropriate to laugh at. They don’t use their imaginations to think of things that are unpleasant. Most of the time, people who seem to be very sophisticated are not able to function in the imagination.

AH: You’ve described your paintings as psychological. What do you mean?

PS: It’s the choice in the first place to put someone in the electric chair. Just to see what it’ll look like. That’s psychological on my part. It makes me into a person who is perhaps troubled. I don’t mind.

AH: You put Jesus Christ in the chair once and had his dad electrocute him.

PS: Oh yeah, I did do him!

AH: Is it important who’s in the chair?

PS: It’s not worth doing if the person in the electric chair is too ordinary. If it’s a bank robber who accidentally pulled the trigger? Forget it. If it’s a totally innocent person, screaming for help? OK.

AH: But, of course, you’ve done an American President more than once.

PS: Oh yes, I’ll do that. I do the ones that people find something wrong with.

AH: How was it different doing the current guy to doing Reagan?

PS: Oh, probably not much. Except he’s much more difficult, the current guy.

AH: More difficult to paint?

PS: Yeah. He’s been done by everybody else. I’d like to be first. With Nixon I was way first. Guston’s picture comes, like, eight years later.

AH: You titled the Trump painting, Abstract Expressionist Portrait of Donald Trump [2018]. You were done with abstract expressionism a long time ago, I thought?

PS: Oh, but it’s always a good movement to make fun of! Or to use in the picture. I don’t mind the art movements. Even though I don’t respect modern art history as an intellectual thing, it doesn’t mean it’s not useful for individual pictures. Cubism is good, especially with female nudes. They’re not square, so if they were to become square, it’s humorous. Surrealism is always good. Means you can do anything you want. Surrealism just means ‘do anything!’ And abstract expressionism means that stuff is flung out, and it looks like it just came down.

AH: If cubism’s humorous with the female body, why is abstract expressionism humorous with Trump?

PS: Same reason, I guess. It just is! I get an idea for a picture and I feel lucky. I’m not a serious artist. Though I would like my pictures to be taken as seriously as a serious artist’s pictures.

AH: Do you find that people respond in a serious way? If you insult them, they must.

PS: I don’t know what happens. I let it slip by and try to focus on the next picture. Another motivation of these pictures, which I should mention more often, is that I would like them to be as way over the top in figurative art as Donald Judd’s glass boxes are...is it Donald Judd?

AH: Yeah, it’s Judd.

PS: So you know what I mean. As far as those boxes are from [Auguste] Rodin. With Rodin, you’ve got a proper human body, it’s in bronze. The Thinker [1902]. Donald Judd takes the base that’s beneath and makes that the sculpture. Ok, that’s way over-the-top? Well, I want my figurative things to be as over-the-top as these boxes, but still have their figuration. I’m going into areas I don’t know whether or not I’m serious about.

AH: But it’s important to keep doing that?

PS: If I lose that, I’m totally dependent on ‘the thinkers’. I don’t want anything to do with that. You have to be very careful today, and I’m not really very careful, so I make this mistake fairly often. But I’m one of the few adults in the United States who is capable of making this mistake.

Peter Saul, ‘Pop, Funk, Bad Painting and More’, is on view at Les Abattoirs, Toulouse, until 26 January 2020.