Thinking Through Bollywood’s Class Consciousness

Shiv Kotecha on the long career of playback singer Asha Bhosle

Shiv Kotecha on the long career of playback singer Asha Bhosle

I learned to enjoy Bollywood movies with my maternal grandmother, Kusum, who, when I was eight, taught me how to pirate them onto videotape. She was a woman who enjoyed rituals and, for several years, we came to expect one another’s company on the weekends.

In the early 1990s, Bollywood rentals were scarce in California. We would drive from her home in Fullerton to the Patel Store in the Little India district of Artesia or to the Cash & Carry in Bellflower, if new releases couldn’t be found at the former. You might find a glass vitrine with a stack of VHS tapes at the back of a grocery store. A spiral notebook might be attached, listing who had rented what. We would pick five or six unfamiliar titles – with more or less familiar names – mostly at random.

Music has been part of Bombay filmmaking since its first sound film, Ardeshir Irani’s Alam Ara (1931), inheriting its structure from the social-realist narratives of Urdu Parsi Theatre and from regional traditions like ramlila, nautanki and tamasha, which spliced together loose adaptations of William Shakespeare’s plays with dozens of song-and-dance routines. Filmi gaana (or Bollywood songs) do not extend or advance the plot as much as they ask you to assess, through exaggerated literalisms, the crises of affection a shared language alone fails to express. Take, for instance:

I have shown coquetry, and you have moved jerkingly. Should I go on noodling my waist like this? Why? Have you felt alarmed? 1

Or:

If the moonlight is saying something to the moon, Who is the one saying something to you? 2

A curdling sentimentality motivates Bollywood’s maximalist form. The rules about continuity in Western film – those that, say, suture an action (a first encounter, a drunken dinner with friends, a rite that, before you are really full conscious, marries you off to your cousin) to a certain space and time (a train carriage, a mother-in-law’s boudoir, a Swiss Alp) – are disobeyed in favour of producing any number of visual or aural excesses. Especially during musical numbers, montage is freed from the imperative to provide shape or texture to a film’s constructed world to, instead, celebrate the novelty of appearance: hundreds of unbidden bodies populate scenic landscapes; lightning strikes, outfits change.

Bollywood songs are lip-synched by the actors. Music directors arrange the melody and instruct the lyricists and the unseen playback singers to emphasize what’s happening on screen. ‘Kill you,’ the actor Parveen Babi whispers in Namak Halal (1982), before lip-syncing to the disco track ‘Jawani Jaaneman’. Babi plays Nisha, a double agent disguised as a dancer who arrives in the film’s penultimate act and vows to murder the male protagonist: ‘Kill you! I want to kill you … I will kill you!’ she yells into a phone. Nisha’s self-possession springboards her onto a nightclub stage where she’s backed by a band and a blown-out Giorgio Moroder-style beat. As in the video for David Bowie’s ‘Heroes’ (1977), multiple exposures replicate the figure of Nisha in a circle hovering above the stage set. The camera sways to and from the dancer, convulsing between verses. She strums her air guitar, laughs to herself and lip-syncs:

Look – look at how a killer looks at you!

I’ve found my – ha, ha – one!

What’s this – ha, ha – something seems wrong?

My arch enemy’s my beloved?

The fowler fell in love with the bird.

The actual singer of ‘Jawani Jaaneman’ was Asha Bhosle. In her 60-year career, she recorded songs for generations of actors in Bombay cinema, as well as the many other film industries across the South Asian subcontinent. Born into a theatrical family in 1933, Bhosle is one of four siblings, all of whom pursued Bollywood careers. Along with her sister, Miss Lata Mangeshkar – whose dulcet playback style, lauded for its Brahmin politeness, was celebrated long before Bhosle rose to fame – she became a household name for myself and most non-resident South Asians I know. In 1949, aged 16, Bhosle eloped and married the music director Ganpatrao Bhosle who, according to an article by her daughter Varsha, published in Gentleman in 1993, kept her singing through the night:

The earliest memory I have of my mother […] is a fleeting montage of doorbells rung very late in the night, a sobbing woman hugging me back to sleep, the strains of strange, repetitive singing emanating from behind a closed door … I bang on the door wanting to go in but am roughly pulled away by a man when the music threatens to cease.

From the 1940s through the late 1960s, Bhosle landed only a handful of jobs. After her husband’s death in 1960, Bhosle met and fell in love with R.D. Burman, a younger, whizz-kid producer with whom she revolutionized the Bollywood sound. If her rival singers’ task was to guarantee, through their voice, mastery of tone – the deployment of voice as craft – Bhosle used her brassy contralto to short-circuit how the performance of femininity (and ethnicity) could be heard. She added variations to her word pronunciations, cadence and pace that did not flatten her Marathi-inflected vernacular, but let it percolate through her high peaks, in her half-words. She paved the way for vocalists like Ila Arun, Hema Sardesai and Usha Uthup, whose husky, androgynous registers roiled the industry’s desire to purge itself of subjects who were from a lower caste or non-gender conforming. Bollywood wanted to project cosmopolitanism, so Bhosle improvised, absorbing her cues from British psychedelia, American jazz, Arabic and Bengali folk music, calypso and cabaret. Despite her physical absence, when Asha-ji (as she is also known) sings, the on-screen male protagonists’ lusty aims are briefly upended: they pause, as if to consider who could do what to whom.

This August, I went back to California to visit my parents. Nearby wildfires created thick, ash-filled columns of smoke between their home and the next. We watched Ram Gopal Varma’s paean to Bollywood, Rangeela (1995). The plot centres on Milli, a young dancer hungry for star power, caught between two suiters: Munna, her socialist best friend and secret admirer, and Raj, an actor and film financier. Above the clatter of Mumbai street traffic, Rangeela’s title cards roll alongside a slideshow of black and white photographs of celebrated actors, all of whom have at one time been voiced by Bhosle. In the film’s opening shot, Urmila Matondkar, who plays Milli, is watching a roadside peep show (conceivably her film; i.e. Rangeela, the film watched by us). Varma lets a few moments of silence pass before allowing Bhosle’s comeback song, ‘Rangeela Re’, rise up above the ambient noise. Milli slowly stands up, sliding her hands down her body, then doffing her cap. I want to read it as a scene of lesbian longing, but Matondkar’s Chaplinesque gestures deflate the tension, replacing sex with farce.

While Milli – fair, middle-class – begins to climb the ranks as a film star, her lover-friend, Munna, a Mumbaiya tapori (vagabond), entreats her to live, like him, by pilfering from the streets. The rich overproduce, he argues, so there’s plenty to get by on. The tapori was a familiar character type in 1990s Bombay cinema: typically a lower-class male and small-stakes gangster, he would act, for the viewer, as a social barometer of his neighbourhood. Like the girls trafficked in to perform an ‘item number’, or sexy dance song, tapori exist exclusively at the periphery of the Bollywood filmic narrative, skirting its stodgy, conservative mores by only ever being found in the flickering shadows of the cinema hall. The tapori speaks bambayya, an urban dialect ‘formalized’ by this character type to signify the working class and, in this particular case, to revel in a language unheard by the state. The first time we see Munna, he is standing outside a box office, selling black-market tickets to a sold-out screening. A mesh tank top hugs his sweaty torso and the ends of a patchwork silk shirt are tied in a knot above his midriff. Frisked by a near-sighted policeman, Munna pretends to surrender. He takes a drag off his spliff, sneaks the pirated tickets into the cop’s hat and calls out directly to anybody listening:

Hey brothers, look! The perpetrators of the Bombay riots weren’t convicted. Millions were embezzled in the stock market. But did they arrest anybody? And me, a simple man who comes to see a film, is harassed! It’s your rule anyway – what will happen to this country, yaar [buddy]!

He disappears into the movieplex arm in arm with another tapori, where they sit transfixed by Bollywood’s commercial, candied frame, inside of which India’s cant political realities can be impolitely softened, one beatific Asha Bhosle track after another. It’s not unusual for actors who live and work on the South Asian subcontinent to also be nationalists, so it wasn’t surprising to see both Bhosle and the actor Aamir Khan (who played Munna) at Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s second-term inauguration in 2019, championing a Hindu-supremacist administration that supports mass incarceration, lynching, institutional murder and acts of terror. Bombay cinema travels the path of least resistance, which has let Bhosle become part and parcel of Indian public life; her voice continues to be heard inside shops and blaring from car radios across India and its diaspora, over the same channels that spew Modi’s cultish oratory. Beguiled by one, and repelled by the other, I feel disrupted; perhaps this is the impossible structure of feeling that Bollywood always intended.

This article first appeared in frieze issue 215 with the headline ‘Out of Earshot’

Read frieze editor Andrew Durbin in conversation with Shiv Kotecha about this essay here.

1 P.K. Mishra (lyricist) and A.R. Rahman (music director), Hindustani, 1996, directed by S. Shankar. Translated from Hindi by the author.

2 Mehboob Kotwal (lyricist) and A.R. Rahman (music director), ‘Tanha Tanha’, Rangeela, 1995, directed by Ram Gopal Varma. Translated from Hindi by the author.

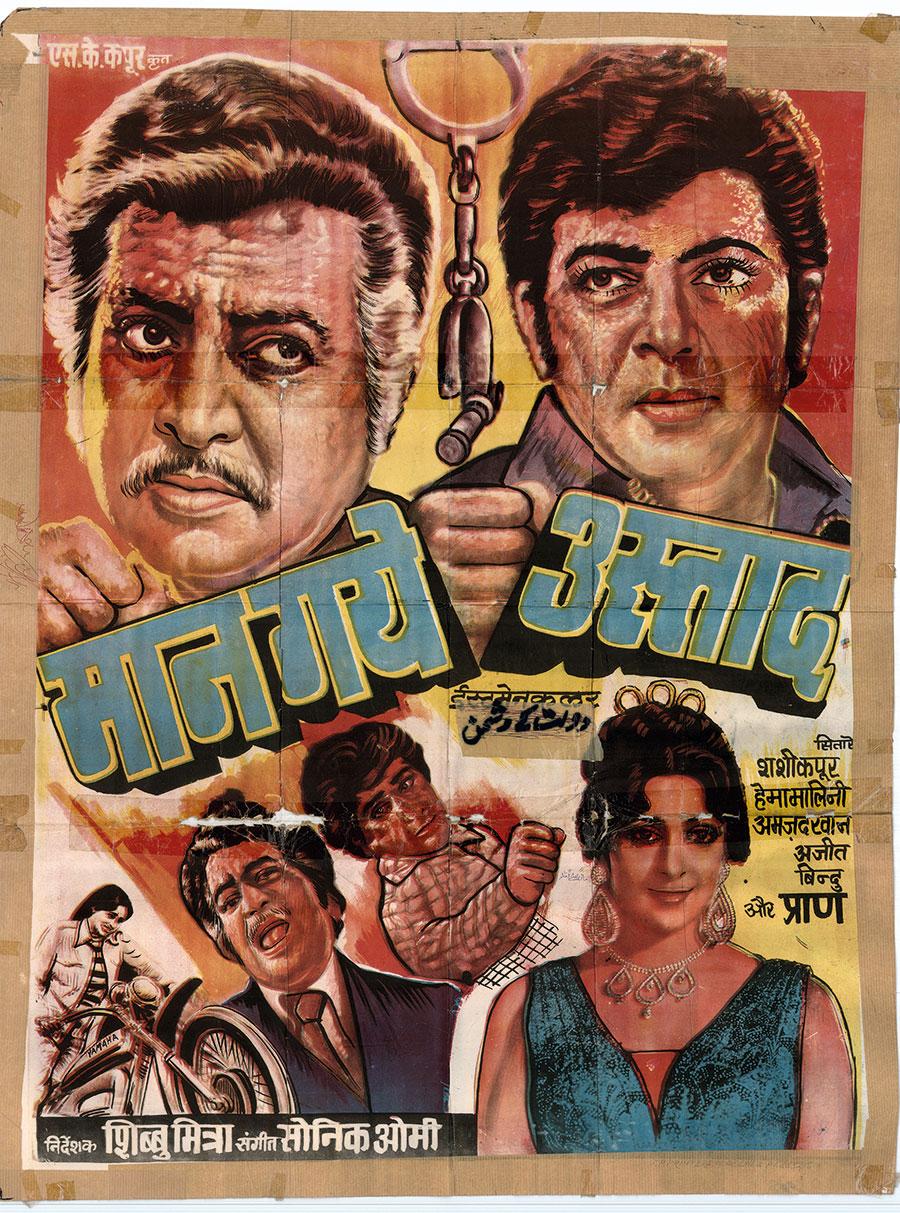

Main image: Rajkumar Kohli, Badle Ki Aag, 1982, film poster detail. Courtesy: Desimovies.biz