Like a Thousand Knives Being Sharpened: a Tribute to Glenn Branca 1948–2018

To experience the music of the composer, who passed away last week at the age of 69, was to hear something tense, physical, almost pugilistic

To experience the music of the composer, who passed away last week at the age of 69, was to hear something tense, physical, almost pugilistic

When John Cage was asked about Glenn Branca’s music in 1982 he remarked: ‘If it was good intentions he was demonstrating, with vehemence and power, it would be one of these strange religious organizations we hear about. Or if it was something political it would resemble fascism. In neither case would I be want to be part of it.’ Branca, who passed away last week at the age of 69, would later include the full 18-minute recording of Cage’s broadside against him on his 2007 album Indeterminant Activity of Resultant Masses; so I suspect, although I don’t know, that he might have been quietly pleased by the disapproval of this modernist titan. Not for any political reasons, but because Branca emerged from a time when – save for one or two older figures you might admit to your pantheon because nobody else would have them – it was your artistic duty to reject all that your forebears wrote, painted, choreographed and composed. Now we line up to honour them at benefit galas and congratulate ourselves for ‘rediscovering’ them, as if they were old letters forgotten in the attic rather than human beings busy living and making. In an interview with Vice magazine in 2016, Branca complained ‘I don’t like being called a legend. This whole idea of me being some kind of leftover from the past is extremely irritating to me, because that is not what I am. I’m very much here, and I’m very much working.’ Yet the composer was ever the contrarian. Talking to The New York Times in 2016, he said: ‘I don’t change. This is something critics always talk about, but has no relation to the way I work. I don’t move on. I do new things, but I don’t leave the old ones behind. I’m simply adding to my repertoire of ideas.’

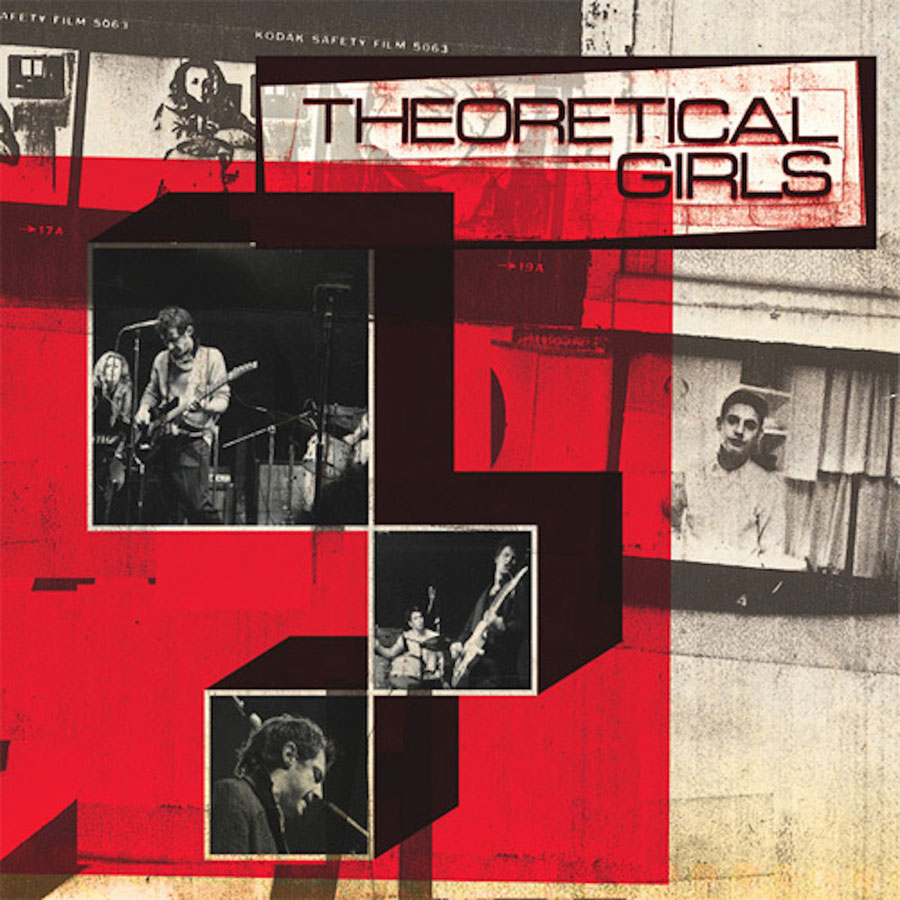

Which makes an ironic kind of sense, given one of his early music projects was called The Static. With another band Theoretical Girls, formed with musician Jeffery Lohn in the downtown New York of 1977, he aimed to ‘change the concept of rock.’ Theoretical Girls could never achieve their ambition singlehandedly, but they and other bands loosely grouped under the No Wave banner – including DNA, James Chance & The Contortions, Mars and Teenage Jesus & The Jerks – certainly helped detune rock out of blues-based rock’n’roll and into a rawboned, textured and self-aware key. Along with composers including Elliott Sharp and Rhys Chatham (who arguably had a big influence on Branca), and working with musicians including Barbara Ess, Christine Hahn, Ned Sublette, Lee Ranaldo, David Rosenbloom, Jeffrey Glenn, Thurston Moore, Stephan Wischerth and more, Branca soon began writing works for electric guitars, using minimalist processes and unconventional tuning systems.

Branca’s first solo recording, the EP Lesson No. 1 for Electric Guitar released in 1980, begins with an alternating four-note sequence and phasing techniques that could be straight out of a Steve Reich piece, but soon picks up momentum, becoming a juggernaut of ringing guitars and piercing harmonic overtones, motor-driven by tom-toms, cymbals and one Harry Spitz on ‘sledgehammer.’ In Lesson No. 1 can be heard the template for bands including Sonic Youth (whose members Moore and Ranaldo played on the original recording) and Swans. With the title of his next release, The Ascension (1981), Branca nodded to Olivier Messiaen and John Coltrane, exploring more deeply the sonic effects of alternative tunings, overtones, feedback, and loudly cranked guitars playing in unison. David Bowie regarded The Ascension highly. In an article for Vanity Fair in 2003, Bowie wrote: ‘What at first sounds like dissonance is soon assimilated as a play on the possibilities of overtones from massed guitars. Not Minimalism, exactly – unlike La Monte Young and his work within the harmonic system, Branca uses the overtones produced by the vibrations of a guitar string. Amplified and reproduced by many guitars simultaneously, you have an effect akin to the drone of Tibetan Buddhist monks but much, much, much louder […] Over the years, Branca got even louder and more complex than this, but here on the title track his manifesto is already complete.’

Branca’s influences, which stretched from The Kinks to mid-20th century European modern composition, helped develop an approach to music that his minimalist forebears in the US had suggested at, bringing ideas from popular music into contact with modern composition. Writing in The Village Voice in 1994, musicologist Kyle Gann observed: ‘Branca keeps his worlds almost schizophrenically separate. To rock critics he'll talk Aerosmith, the Ramones, the [New York] Dolls, Henry Cow and Orchestra Luna ... With me he uses a different set of references, equally obscure: Kryzsztof Penderecki, Dane Rudhyar, Hans Keyser.’

Whether in his symphonies for massed electric guitars, in which volume was an important compositional element, or in works scored for more conventional orchestras, Branca’s music sounded like a thousand knives being sharpened, each overtone like sunlight glinting off a steel blade. In some senses, he was a maximalist making use of minimalist processes and the result was a kind of Grand Guignol minimalism. To experience his music live – as I did in 2007 when I helped organize a concert at the Roundhouse, London, of his Symphony No.13 (Hallucination City) For 100 Guitars, for Frieze Music – was to hear something relentlessly tense, physical, almost pugilistic. Even where his music became more stately, widescreen in perspective – such as with his 1983 Symphony No. 3 (Gloria) or the optimistic and bright-sounding Symphony No. 9 (Free Form) (1993) – there was always a sense of the ominous to Branca’s work, a lugubrious weight.

For me, artist Robert Longo’s drawing for the cover of The Ascension perhaps best describes Branca’s music. It depicts two men in suits against a white background. One of them is Branca, lifting another unconscious man off the ground. It’s hard to tell whether Branca is rescuing the other figure, or has just committed some act of violence on him and is trying to work out what to do with the body. When I see this ambivalent image I can’t help but think of Branca in the early 1980s, bludgeoning and dragging the principles of musical minimalism underground into a loud, dark club, making classical and post-punk share a stage, whether they wanted to or not.

Main image: Glenn Branca performing at the Paradiso in Amsterdam, Netherlands on 2nd February 1988. Photograph: Frans Schellekens/Redferns