Tributes to John Ashbery (1927-2017)

Reflections, a favourite verse, and a new poem dedicated to one of the English language’s most renowned poets of the past century

Reflections, a favourite verse, and a new poem dedicated to one of the English language’s most renowned poets of the past century

Pablo Larios

Pablo Larios is associate editor of frieze. He is based in Berlin, Germany.

In his Paris Review interview published in 1983, the poet John Ashbery recalled, admiringly, the closing of an Ingmar Bergman movie: ‘She's telling the story in the dressing room of a theater where she is about to go on and perform in a ballet. At the end of it she says, “But I am happy.” Then it says, “The End”.’

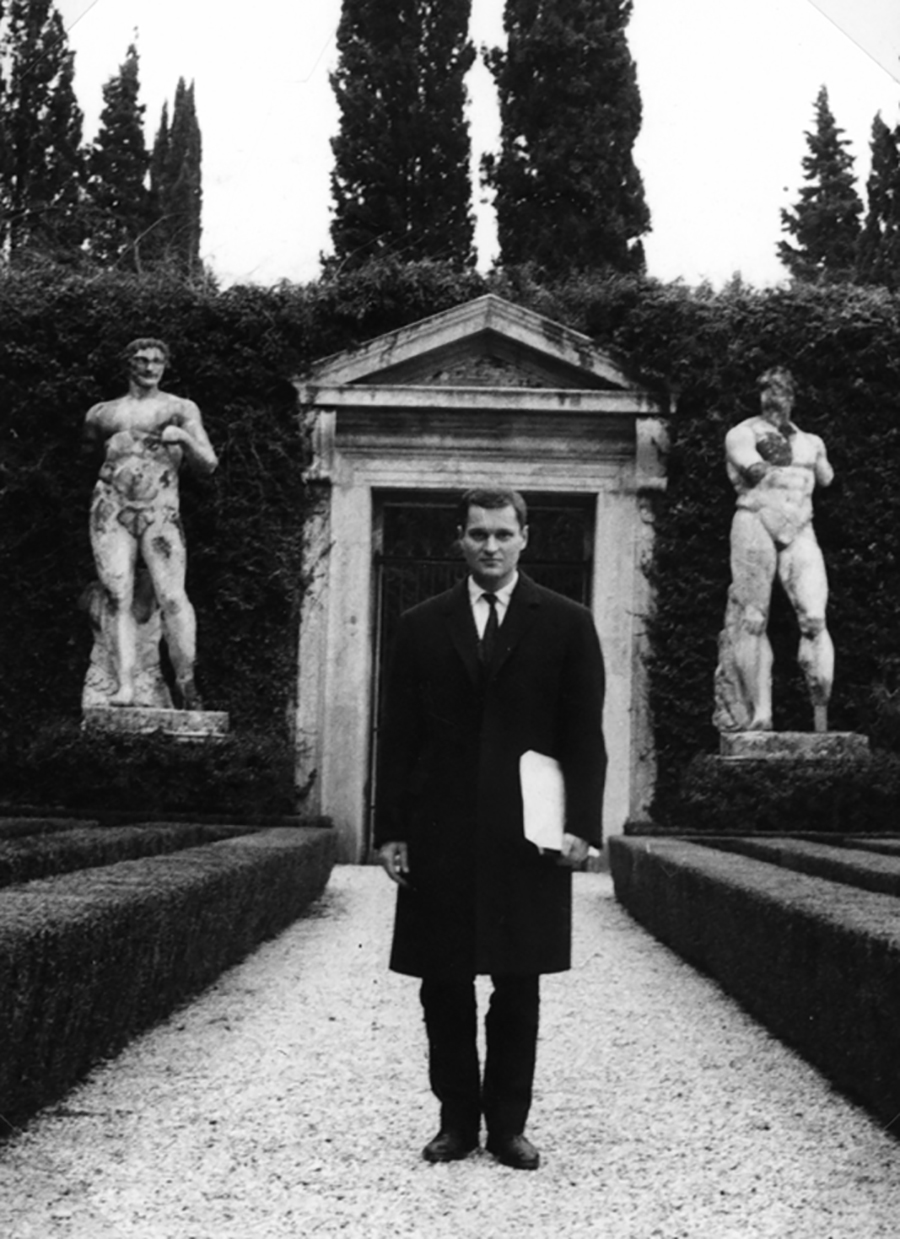

Ashbery’s death on 3 September 2017 sent shivers to the many people who have known, studied with or cherish the work of one of the English language’s most renowned poets of the past century. Ashbery, who was 90, was known for a hallucinatory verse that flickered with lush ambiguity yet managed to be intimately and widely loved. Ashbery’s ties to art were deep and capacious, from the painting (c.1524) by Parmigianino that inspired his poetry collection ‘Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror’ (1975), to the fact that he worked regularly as an art critic for many years, first in Paris and later New York. Ashbery’s close friend Frank O’Hara, in his 1954 poem ‘To John Ashbery’, wrote ‘I can’t believe there’s not / another world where we will sit / and read new poems to each other / high on a mountain in the wind’.

In tribute, we present a new poem by Charles Bernstein written in dedication to John Ashbery, a favourite verse by poet Andrew Durbin, and reflections by poets Oli Hazzard and Lyn Hejinian, writer Olivia Laing and musician and writer David Grubbs.

Lyn Hejinian

Lyn Hejinian is a poet, translator and publisher. She lives in Berkeley, California, and teaches at the University of California, Berkeley.

Immediately upon learning of John Ashbery’s death, I went to my bookshelf and, more or less at random, pulled out Some Trees (1956). I turned to ‘The Picture of Little J.A. in a Prospect of Flowers’. Given the title, this might seem a sentimental choice, but not if one reads the poem. It is sassy and defiant. But, of course, it also foresees something: his death (in his knowledge of the world Ashbery would have known he would eventually die) but also the delay (but not failure) of a full and comprehending reception of his capacious, magnificent work.

At the end of the poem he writes:

Virtue is really stubbornness

And only in the light of lost words

Can we imagine our rewards.

The prospect for any poet in the modern Western world is bleak. They are deemed anachronistic, trivial, ‘elite’ (though also as ridiculous as clowns), and, by all measures, irrelevant. In his long and indefatigably creative life, John Ashbery exercised virtue–stubbornness, yes, but also magnificence and affective plenitude. He was one of the greatest poets of human history; his own history (the future of his work) is yet to come.

Charles Bernstein

Charles Bernstein is a poet and essayist. His most recent book is Pitch of Poetry (University of Chicago Press, 2016). From the University of Pennsylvania he co-runs PennSound: an archive of poetry and audio recordings, the John Ashbery collection of which can be found here.

‘If Sappho were a UFO’

And I were a genie

We’d dance on the surface of Pluto

And dine at Ipanema beach in Rio.

Nothing much else

Glues me to this shredded fabric

Of the marvelous, on sale all these years

With no buyers and just three

Authorized sellers. I’d made it almost to

Mars then went home, too much

Mud in those parts, and I missed

The smell of home ground

Even if it turned out to be imported.

3 September 2017

for John Ashbery

Andrew Durbin

Andrew Durbin is the author of Mature Themes (2014) and the novel MacArthur Park (2017), both published by Nightboat Books. He recently edited the chapbook collection Say Bye to Reason and Hi to Everything (2016), published by Capricious. He co-edits the press Wonder and lives in New York, USA.

‘To Redouté’ from The Tennis Court Oath (1962) by John Ashbery

To true roses uplifted on the bilious tide of evening

And morning-glories dotting the crescent day

The oval shape responds:

My first is a haunting face

In the hanging-down hair.

My second is water:

I am a sieve.

My only new thing:

The penalty of light forever

Over the heads of those who were there

And back into the night, the cough of the finishing petal.

Once approved the magenta must continue

But the bark island sees

Into the light:

It grieves for what it gives:

Tears that streak the dusty firmament.

Oli Hazzard

Oli Hazzard is the author of Between Two Windows (Carcanet, 2012) and Within Habit (Test Centre, 2014).

I have this week been reading amazing tributes to John Ashbery and to his work, and at the same time finishing my book about him. Before submitting the final draft on Thursday, I was mainly engaged in the lugubrious task of changing the tense in which I referred to him. Combing through my manuscript, and thinking about very beautiful and idiosyncratic and true-seeming descriptions by Rae Armantrout and Ben Lerner and so many others of the experience of reading his poems, I noticed for the first time that, despite lots of analysis of how his poetry works, I had made virtually no attempt to describe what reading Ashbery feels like. This wasn’t a conscious choice, I don't think. But on reflection it seems like a signal to myself – as it has been for many other people I know – of the universal scale of his work to me. I still respond to it with stupefaction. This dumbstruckness struck when I got together with some friends in Edinburgh a few nights ago to read his work. When the subject of favourite pieces first came up, I found myself thinking: uhhhhhh. How – and especially now – would you even begin describing this poetry and what it has meant to you, knowing that the moment you concentrate on one aspect of it another equally crucial property is pushed out of view, however momentarily? This very basic question of perspective and time feels like one I should have dealt with when I started reading his work ten years ago, but feels as urgently unanswerable today as then. The only way to talk satisfactorily about Ashbery’s work is to acknowledge that it has ‘the beauty of a single word’. This is, of course, what he wanted: to create a work so transparent no critic could talk about it, for nature, not art, to usurp the canvas. Despite knowing this, I have always found myself wanting to say something more about it anyway, because this feeling of being overwhelmed and stupefied and swept away seems somehow synonymous with love.

Ashbery was a major minor poet. I use these stupid terms because he used them, and found them useful because precision can be reductive, and vagueness allows for and even encourages disagreement and elaboration. (Vague/wave is maybe the central pun of his punishingly pun-riddled oeuvre.) He is major in the sense that he made what had once seemed a primary way for poets to engage with the world – the explicit elegiac address of, say, W.B. Yeats, Robert Lowell and Geoffrey Hill – appear too simple, too little like the actual experience of living in history. Ashbery lived in history, but where are his poems about Vietnam, AIDS, Iraq? Nowhere and everywhere: history is braided into the living fabric of all of his poems. He is minor in the sense that he achieved this massive shift not just through his staggering ambition and ability but through humility, play, sympathy, disinterest, goofiness, vagueness, digression, tenderness, ventriloquism, shyness and boredom. His is a fully human poetry, in which, as it is with us, the marginal is thrust constantly and unexpectedly into the centre of things. It is a measure of his achievement that I can find Ashbery most sympathetic and understanding when I am my smallest self, and most energizing and enabling when I want to change.

I read back through the above and am surprised and embarrassed by its earnestness, its narrowness, how I’ve pushed out of frame the fact that he’s the funniest poet I’ve ever read, and that the few times I met him he was friendly and patient and kind. But one of the things he has taught me to accept is just that, knowing that other people – to whom he has brought me immeasurably closer – will say the things that I don’t. I’m going to finish by quoting Walter Pater on Botticelli. It seems to me entirely apt, and a guarantee of the future life of his poetry, that the most accurate description of it was written decades before he was born:

... what Dante scorns as unworthy alike of heaven and hell, Botticelli accepts, that middle world in which men take no side in great conflicts, and decide no great causes, and make great refusals. He thus sets for himself the limits within which art, undisturbed by any moral ambition, does its most sincere and surest work. His interest is neither in the untempered goodness of Angelico’s saints, nor the untempered evil of Orcagna’s Inferno; but with men and women, in their mixed and uncertain condition, always attractive, clothed sometimes by passion with a character of loveliness and energy, but saddened perpetually by the shadow upon them of the great things from which they shrink. His morality is all sympathy; and it is this sympathy, conveying into his work somewhat more than is usual of the true complexion of humanity, which makes him, visionary as he is, so forcible a realist.

Olivia Laing

Olivia Laing lives in Cambridge, UK. Her book The Lonely City: Adventures in the Art of Being Alone (2016) is published by Canongate.

Late, up in my room, night rain, three people tweet about Ashbery. That’s how I heard about Bowie, that’s how I heard about my friend Alastair Reid, that’s how it is these days. Once I thought I was sitting opposite Ashbery on the 1 train, his big square head. I got all the way to Cathedral Parkway before I realised it was Edmund White. In Chelsea, years ago, there was a show called ‘Ashbery Collects’, his front room remade, his rugs and pictures and Daffy Duck cartoons. Something sad there, misplaced. He washed language and put it back on the shelves all wrong. It looked so much better that way. The language will be arriving later, I misread this morning. Language = luggage, baggage, the ongoing upsettingness of water in the air. Ashbery has died, comma, Ashbery has died. I’m sorry about the pillars of grass, who are now illegal and will be deported. There is nothing to do for our liberation, except wait in the horror of it. And I am lost without you, the sweet black smuts moving upwards.

David Grubbs

David Grubbs is a musician, professor of music and founding member of Gastr del Sol. His latest record Creep Mission is out with Drag City later this month.

In addition to loving Ashbery's work, I was deeply moved when he granted permission to use the following excerpt from ‘The System’ (1972) as the epigraph to Records Ruin the Landscape (2014):

The rejected chapters have taken over. For a long time it was as though only the most patient scholar or the recording angel himself would ever interest himself in them. Now it seems as though that angel had begun to dominate the whole story: he who was supposed only to copy it all down has joined forces with the misshapen, misfit pieces that were never meant to go into it but at best to stay on the sidelines so as to point up how everything else belonged together, and the resulting mountain of data threatens us ...

‘Three Poems’ is my favourite work by Ashbery. It's one of the great reading experiences of my life and I can never recommend it highly enough.

When Ashbery’s husband David Kermani conveyed Ashbery’s approval of the request for permission, he noted that ‘hearing Cage's Music of Changes at the legendary New Year's Day concert in 1952, which he attended with Frank O'Hara, broke JA's long spell of writer's block and made him realize that there was a whole new way to go about writing poetry.' (Shiver.)

Main image: John Ashbery, 1975. Courtesy: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.; The Peter Hujar Archive; Matthew Marks Gallery, New York; Photograph: © Peter Hujar