Universal Archive

Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain

Museu d'Art Contemporani de Barcelona, Spain

Of the blockbuster cultural initiatives that have been inspired and hosted by the Catalan capital in 2008, no two could be further apart than Woody Allen’s dismaying Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008) and the MACBA exhibition ‘Universal Archive: The Condition of the Document and the Modern Photographic Utopia’, a hugely ambitious genealogy of the documentary form of photography (co-produced and touring to the Museu Colecção Berardo-Arte Moderna e Contemporãnea, Lisbon). While Allen’s facile vision of Barcelona and the ‘flamboyant artist’ character of his male lead (played by Javier Bardem) demonstrated the ‘Olé!’ version of the city’s self-branding, ‘Universal Archive’ was difficult to digest by comparison. The exhibition, which comprised some 2,000 photographs, presented a tough and awkward depiction of the grittier sides of the city and uncompromisingly explored the often-unglamorous role of the artist–documentarian within it.

The exhibition’s wonderfully unwieldy scale and its dizzying categorization refused benign consumption. Both its strength and its weakness lay in the fact that it was really three projects under one roof, covering a time span from 1850 to the present day. Even three visits did not truly do the show justice, but its exhausting extent nevertheless perfectly complemented the archival strategies it presented, as if its densely-installed two floors – encompassing legions of framed prints and closely-packed vitrines and several digital slideshows – were inspired by a labyrinthine Borgesian tale. For many visitors, the stamina required to experience it could have been off-putting. There are only so many images of shift workers, tract housing, farmland or grain silos that one can absorb. Yet, attempting to embrace such immense amounts of data – whether Timothy H. O’Sullivan’s territorial surveys of the USA in the 1860s and ’70s, August Sander’s collective portrait of the German people in the late 1920s, or the Mass-Observation movement in Britain from 1937 until the early 1950s – provided the exhilarating, if relentless, basis for the whole project.

Spanning Lewis W. Hine’s bleak records of child labour in the early 1900s and Dorothea Lange’s now-iconic shots of destitute pea-pickers during the depression of the 1930s to the glorious and curious wonders published in LIFE magazine and the optimistic travel guides produced by Spanish publisher Ediciones Destino, the major axis of ‘Universal Archive’ traced documentary methodologies through sections titled ‘Politics of the Victim (1907–43)’, ‘Public Photographic Spaces (1928–55)’, ‘Comparative Photography (1923–65)’ and ‘Topographics, Landscape Culture and Urban Change (1851–1988)’. Many, if not all, of photography’s pioneering practitioners were represented, yet the exhibition was driven by an examination of strategies rather than a series of star creators. After all, many of the photographers included were editorial photographers, journalists, government surveyors, sociologists (Pierre Bourdieu), anthropologists (Margaret Mead), historians (Aby Warburg) or simply anonymous; for the most part, photography was presented as a tool and not a knowing instrument of art. The impact of more recent Conceptual photographic projects – including works by Martha Rosler, and Dan Graham’s photographic series ‘Homes for America’ (1967) – as the culmination of the exhibition’s central thesis seemed strangely lost. Or rather, as more recent reflexive archival practices by the likes of Peter Piller, The Center for Land Use Interpretation and The Atlas Group were not included, they seemed almost like forlorn historical phenomena.

Yet, the major contemporary section of the exhibition, ‘2007: Metropolitan Images of the New Barcelona’, comprised the results of a swathe of newly-commissioned photography ‘missions’ throughout greater Barcelona by the likes of MACBA favourites David Goldblatt and Allan Sekula. Goldblatt investigated the area around Llobregat – a mess of diverted waterways, roads and railways, and the site of the city airport – which is straining to assimilate the infrastructural demands of the present, including a new airport terminal and a long-awaited high-speed train line. Goldblatt’s series, ‘Global Connections’ (2007), reveals the zone’s interstitial pockets of activity, such as roadside sex workers and picnicking Turkish truckers.

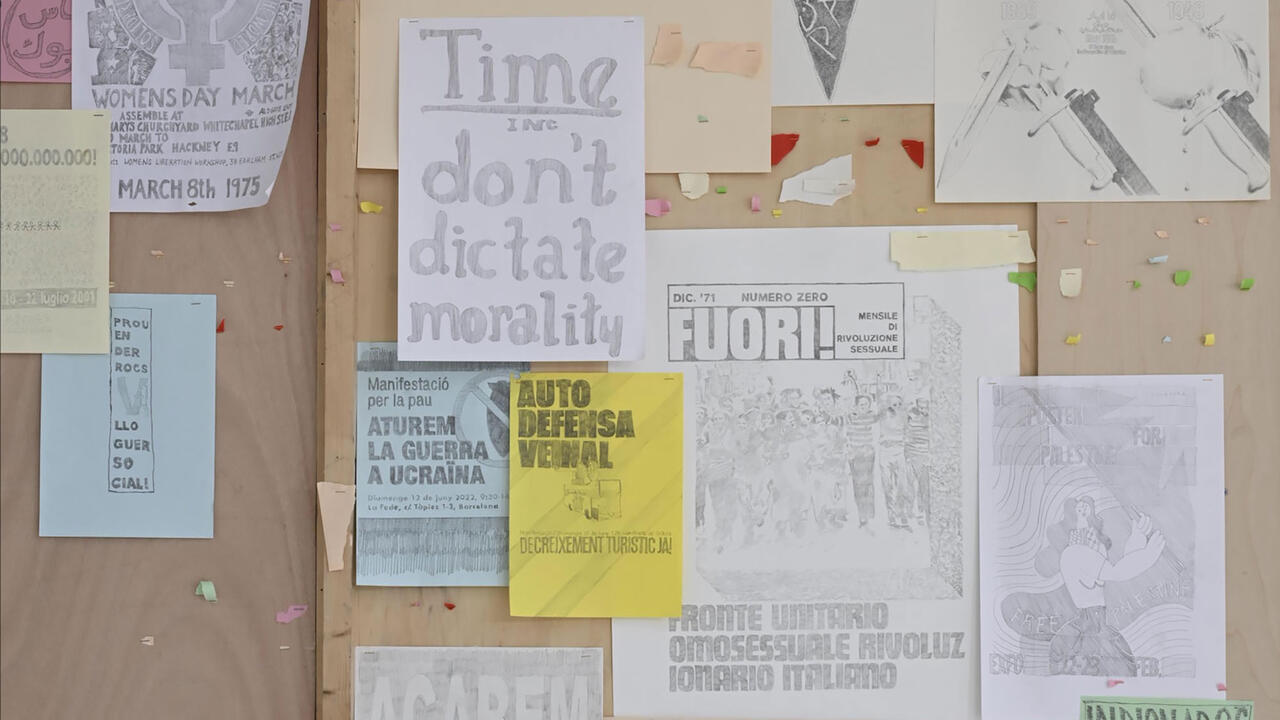

Each of the 16 projects in ‘2007: Metropolitan Images …’ depicts the city and its users with an honest intimacy. In ‘Reclaimed Landscapes: The Heritage of Poblenou’, Lothar Baumgarten shot the semi-derelict, modernist factory buildings of the Poblenou district, part of an industrial heritage largely neglected in the speculative rush to construct the new 22@ zone for ‘creative industries’. For the series ‘Urban Elites: The Weight of Continuity’, Patrick Faigenbaum photographed a powerlist of businessmen and politicians in their workplaces (including several MACBA board members). Gilles Saussier’s account, ‘New diffused centralities: The Oriental Link’, focused on the Chinese wholesalers of Badalona and Santa Coloma de Gramenet; Ahlam Shibli documented the lives of the many South American immigrants who work as carers for elderly Catalans (‘Dependence’); Hans-Peter Feldmann worked in the Raval area around the museum (‘Human Landscapes: From the Myth of the Barrio Chino to the Myth of the Rawal’) and William Klein in the tawdry tourist honey pot of La Rambla (‘The Banalisation of the City Centre: La Rambla’). These tender and essential perspectives on the city’s ‘now’ emerge from its many transformations and assimilations, which are exposed elsewhere in the show, including the Universal Exhibitions of 1888 and 1929, and the ‘Barcelona, posa’t guapa’ (‘Barcelona, make yourself beautiful’) period leading up to the Olympics being held in 1992.

Queues to see ‘Universal Archive’ were unprecedented: MACBA’s difficult show triumphantly connected with a diverse and enthusiastic public – a broad constituency united through long-established and vigorous public discourse concerning urban planning, privilege and marginalization, or the loss of traditional industries. Singling out one image from this multitudinous exhibition is almost heretical, yet a Paris Match photograph captioned ‘André Malraux selects photographs for La Musée imaginaire, 1947’ fittingly graces the exhibition leaflet. With hundreds of pictures arranged on the floor in front of him, in what now resembles a Google Image Search result, Malraux is both a cipher for the curator – and kudos goes to MACBA’s Jorge Ribalta and team – and a stand-in for all our needs to find order in a world of ever-accumulating evidence and images. The one thing in Allen’s film that perhaps did also ring true for this landmark exhibition was its poster strap line: ‘Life is the ultimate work of art.’