The Vexing Present and the Venice Biennale

Can Ralph Rugoff’s ‘May You Live in Interesting Times’ exhibition address histories of narrow nationalism, fascism, and empire head-on?

Can Ralph Rugoff’s ‘May You Live in Interesting Times’ exhibition address histories of narrow nationalism, fascism, and empire head-on?

Susan Sontag sneered at the word ‘interesting’, dismissing it as a bland consumerist credo. Promiscuously tendered, empty of meaning, ‘it is a peculiarly inconclusive way of experiencing reality,’ she wrote in ‘An Argument About Beauty’ (2007). And yet Ralph Rugoff’s title for this year’s Venice Biennale unabashedly embraces the term, side-stepping the burden of a high-flown, high-concept theme. ‘May You Live in Interesting Times’ sports all the Delphic ambiguity and cloying cheer of a fortune cookie. I mean, show me a time that isn’t interesting!

There is a point, or a tidy origin story, at least, to Rugoff’s portentous themelet. In the late 1930s, an illustrious British MP evoked an ancient Chinese curse – ‘may you live in interesting times’ – to describe the anxious world that confronted Britain (and Europe, and the world at large) as war clouds gathered. The curse, it turns out, was apocryphal, but the ‘uncertain artefact’ (Rugoff’s phrase) lingered. And so, in these depressing crisis-ridden times, amid Brexit, Donald Trump and calamitous climate change, said ‘counterfeit curse’ has been repurposed as the premise of a vast art show.

To be fair, we do seem to be swimming in an excess of ‘interesting’ at the moment. This year’s biennale, Rugoff avers, will ‘no doubt include artworks that reflect upon precarious aspects of existence today’. He goes on: ‘Perhaps art can be a kind of guide for how to live and think in “interesting times”.’ Emphasis on the perhaps. Rugoff admits that art is no substitute for politics: it ‘cannot stem the rise of nationalist movements and authoritarian governments in different parts of the world […] nor can it alleviate the tragic fate of displaced peoples across the globe.’

Of course, contemporary art’s nullity in the face of current events is obvious, not least in that tiny precinct of the art world that convenes in Venice every two years, siloed off from the rest of the universe, hemorrhaging white wine on yachts, slinking towards Bethlehem. (The 2017 biennale celebrated its themelessness with a blandly chirpy cri de coeur: ‘Viva Arte Viva!’ or ‘Hooray Art Hooray’. Whether this was a knowing confession of irrelevance or mere laziness, I do not know.)

Rugoff’s modishly vague theme bears more than a passing resemblance to ‘All the World’s Futures’, the 2015 Venice Biennale curated by the late Okwui Enwezor. ‘I cannot remember a time more precarious, more foreboding, than the current moment,’ Enwezor told Michelle Kuo on the eve of his opening. While I confess that sifting through these sorts of temperature-taking proclamations can feel like watching reruns of the Precarity Olympics, Enwezor’s biennale did provide some hopeful glimpses of how art might, on a very good day, respond.

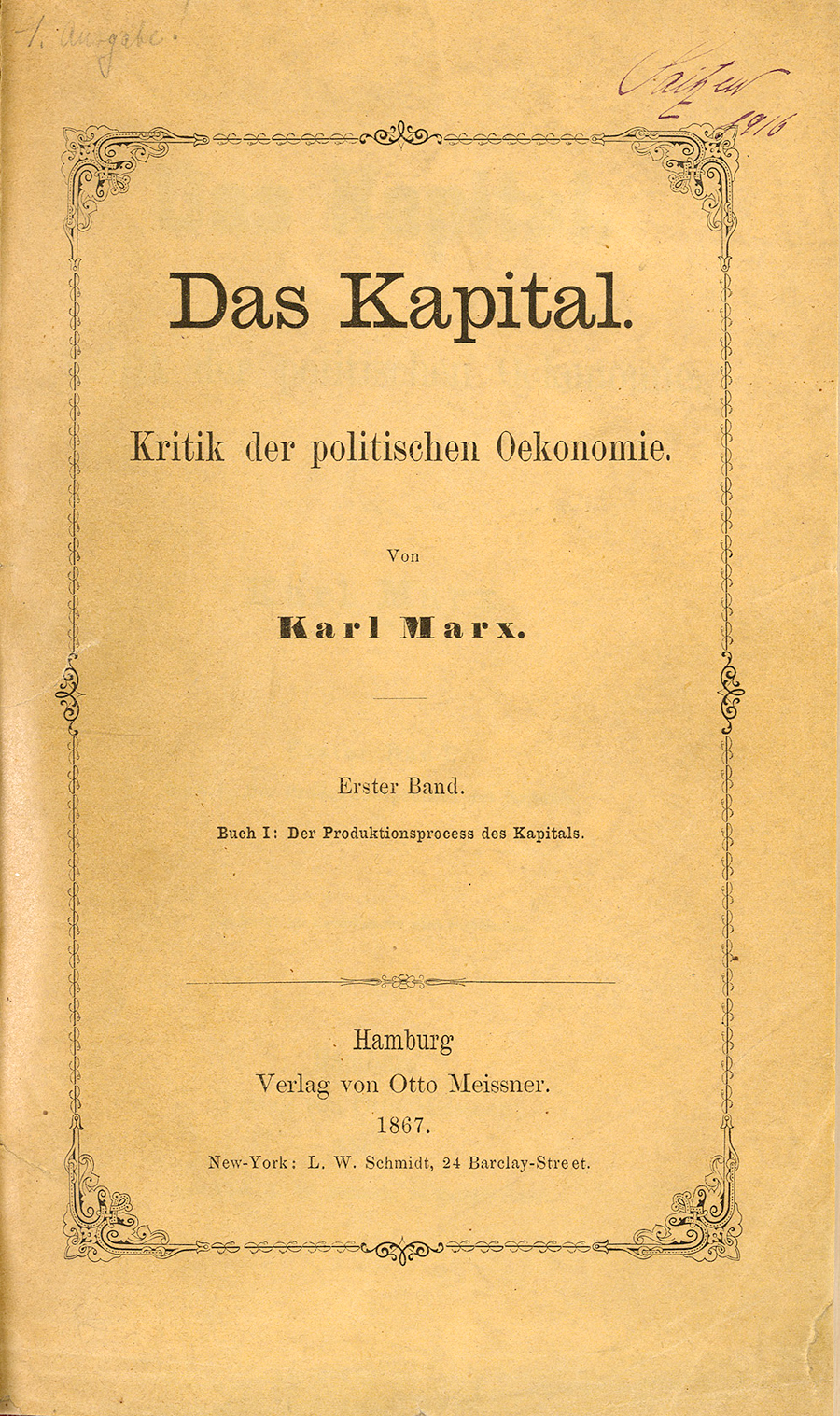

Enter Karl Marx. Throughout the length of Enwezor’s exhibition, for seven gruelling hours a day, all three volumes of Das Kapital (Capital, 1867) were read aloud in the central atrium of the Giardini, providing the Biennale with its spiritual home. The gesture struck some, including myself, as earnest and overdetermined, self-parodying almost, impervious to irony. Critics declared the show strident, morose, even.

But what if Enwezor was ahead of his time? In an era of soaring economic asymmetry, it’s not entirely surprising that people are suddenly embracing the writings of Mark Fisher, the gone-too-soon cultural theorist and critic whose book Capitalist Realism (2009) anatomized a sclerotic collective psyche that literally cannot imagine an alternative to capitalism. Young (and not so young) people are embracing socialism in numbers not seen for decades. Marxism is the muse for literary writers including Anne Boyer, Heike Gessler and Sally Rooney, to name but a few. Art? Think Hannah Black, Neil Beloufa, Bouchra Khalili or Cameron Rowland.

Enwezor’s Marx-minded exhibition included a number of works that remain stuck in my mind, such as Im Heung Soon’s improbably riveting Factory Complex (2014), a film that vividly depicts the exploitation of female workers in South Korea. Jeremy Deller invited performers to sing historical songs of resistance by factory workers to stirring effect. Perhaps the most successful collapse of the biennale’s theme occurred around the edges of the main exhibition, when the activist group Gulf Labor staged a dramatic takeover of the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in order to protest the miserable conditions of workers at that museum’s endlessly delayed Abu Dhabi outpost. (No, the Africans wilting in the sun as they sold selfie sticks to tourists were not part of someone’s art project.)

Rugoff’s aspiration to be vaguely relevant to these interesting times might be seen as a riskily modest enterprise, given a biennale context imbricated in histories of narrow nationalism, fascism, soft power and empire. Enwezor’s proposal was to address those histories head-on. It may be a fantastical sell, the notion that art can offer political lessons or win hearts and minds. Maybe one piece out of 100 will, in Rugoff’s words, help us think through the vital question of how to live in such times. Ninety-nine may die trying. Hedgers will keep elegantly hedging. But maybe that one is quite enough.

Main image: Venice, 2019. Courtesy: Airin Party