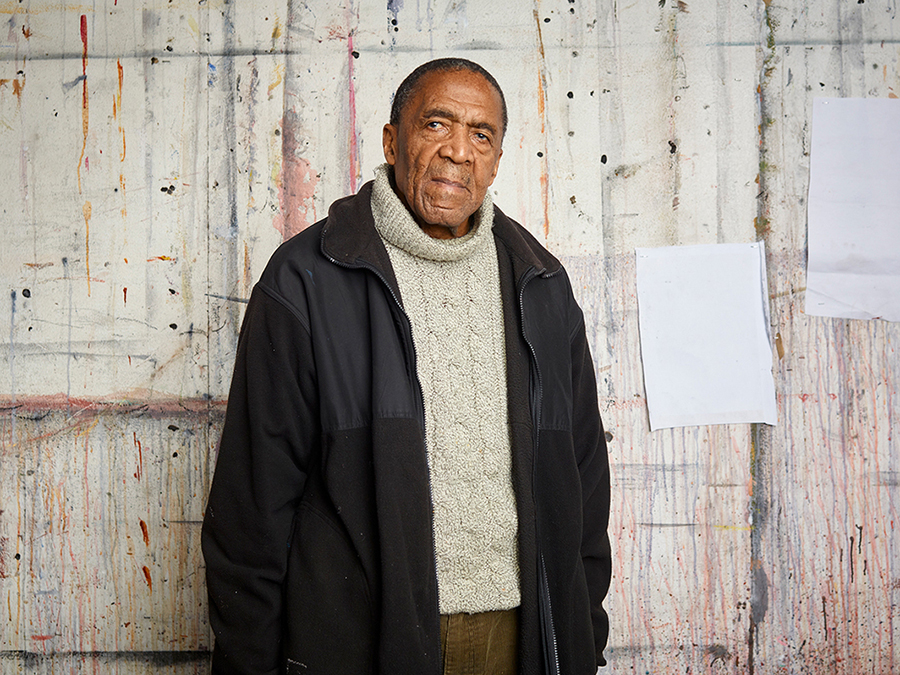

The Virtuosity and Generosity of David Koloane (1938-2019)

The artist, curator, educator and writer, who died on 30 June, was committed to supporting South Africa’s younger artists

The artist, curator, educator and writer, who died on 30 June, was committed to supporting South Africa’s younger artists

A few weeks before his death on 30 June at age 81, David Koloane – an irrefutable figure in South Africa’s tetchy yet vibrant art community – was in Cape Town for the opening of his much-delayed career survey, ‘A Resilient Visionary’. As is protocol at the state-run Iziko South African National Gallery, the opening included an elaborate oratorio. In his keynote address, historian Premesh Lalu praised Koloane, a Johannesburg-born artist, curator, educator and writer, for his ‘virtuosity and generosity’, further adding that his art and activism had made ‘life liveable in the midst of senselessness and violence’.

It was artist Lionel Davis, however, who offered the best insight about Koloane, a soft-spoken doer in a society prone to fumbling and complaint. Davis recalled in 1986 being invited by Koloane and Bill Ainslie, an influential abstract expressionist and frequent collaborator, to attend an artist’s workshop in Johannesburg. Upon arrival, Davis was issued lengths of canvas and a bucket. The freedom to do as he pleased, at scale, confounded Davis, but also liberated his practice. ‘David, I thank you for being who you are.’

News of Koloane’s death was not unexpected – he had been battling cancer in recent years – but was nonetheless met with widespread grief. South Africa’s president Cyril Ramaphosa expressed his condolences. The respect Koloane commanded, especially from artists, flowed naturally from the value he placed on fellowship and association. It was lesson he acquired early on.

When Koloane was 16, artist Louis Maqhubela moved into a house across the street in Alexandra, a township in northern Johannesburg. The two toured galleries together, these early encounters contributing to Koloane’s generous yet also critical eye. In works by white artists of the 1950s and 60s, he recognised a strange and recurring interest in blackness as surface and ornament, while in works by black artists negotiating the white-dominated art market, he often saw compromise and expediency.

Mentored by Ainslie between 1974 and 1977, Koloane began experimenting with various forms of abstract painting – including abstract expressionism, collage and assemblage – as a way to resist the parochial white art market. In his hands, abstraction came to represent a viable and authentic avant-garde practice, one that allowed Koloane agency in visualising his multifaceted experience of Johannesburg.

White dealers resisted his daring. Shortly after Koloane began to explore collage in 1977-78, a prominent Johannesburg gallerist rebuffed his work as ‘un-African’. Even in later years, when he employed expressive figuration to render cityscapes and stray dogs, the latter a potent symbol of violence and insecurity for black city dwellers, South African collectors continued to shun his work.

Alongside his commitment to making serious art, Koloane was a pioneering educator and curator. In 1977, along with Zulu Bidi and Hugh Nolutshungu, he opened The Gallery, Johannesburg’s first black-owned art gallery. He co-curated a number of important exhibitions, including at the Culture and Resistance Symposium-Festival of South African Arts (1982) in Gaberone, Botswana, and ‘Art from South Africa’ (1990), the first major international exhibition of contemporary South African art after Nelson Mandela’s release, held at the Museum of Modern Art, Oxford.

Koloane’s highpoint as a curator, though, was organizing the South African section of ‘Seven Stories about Modern Art in Africa’ (1995) at the Whitechapel Art Gallery. The exhibition drew attention to the 1977 murder in detention of activist Steve Biko and was conceived as a meditation on ‘the pervasive role played by politics’ in South African life and its ‘affects on both victims and perpetrators alike’.

In 1979 Koloane began his long association with the Federated Union of Black Artists (FUBA) Arts Centre, where three years later he met the English sculptor Anthony Caro. That meeting planted the seed for the influential Thupelo workshop series (1985-91), attended by Davis, Kagiso ‘Pat’ Mautloa, Sam Nhlengethwa and many other now-prominent artists. For all its successes in liberating artists from the trap of formalism and cliché, the workshop series also highlighted a real constraint: studio space.

In 1991, with the help of London art collector and philanthropist Robert Loder, Koloane established the Fordsburg Artists’ Studios (now known as the Bag Factory Artists’ Studios) in Johannesburg. ‘Much in the way that subject matter was an issue during the struggle, so too was physical space,’ said Koloane in 2013. ‘By claiming that studio space, we were also claiming the right to be artists. We had the freedom to do what we wanted.’

Main image: David Koloane, New Life (detail), 2016, acrylic on canvas. Courtesy: Goodman Gallery, Cape Town/Johannesburg; photograph: Sean O'Toole