Warp Records at 30: The Best Response to Rave Nostalgia

Few other labels could claim to have cultivated such a coherent philosophy over the years: one which unites the pleasure of partying with its darker side

Few other labels could claim to have cultivated such a coherent philosophy over the years: one which unites the pleasure of partying with its darker side

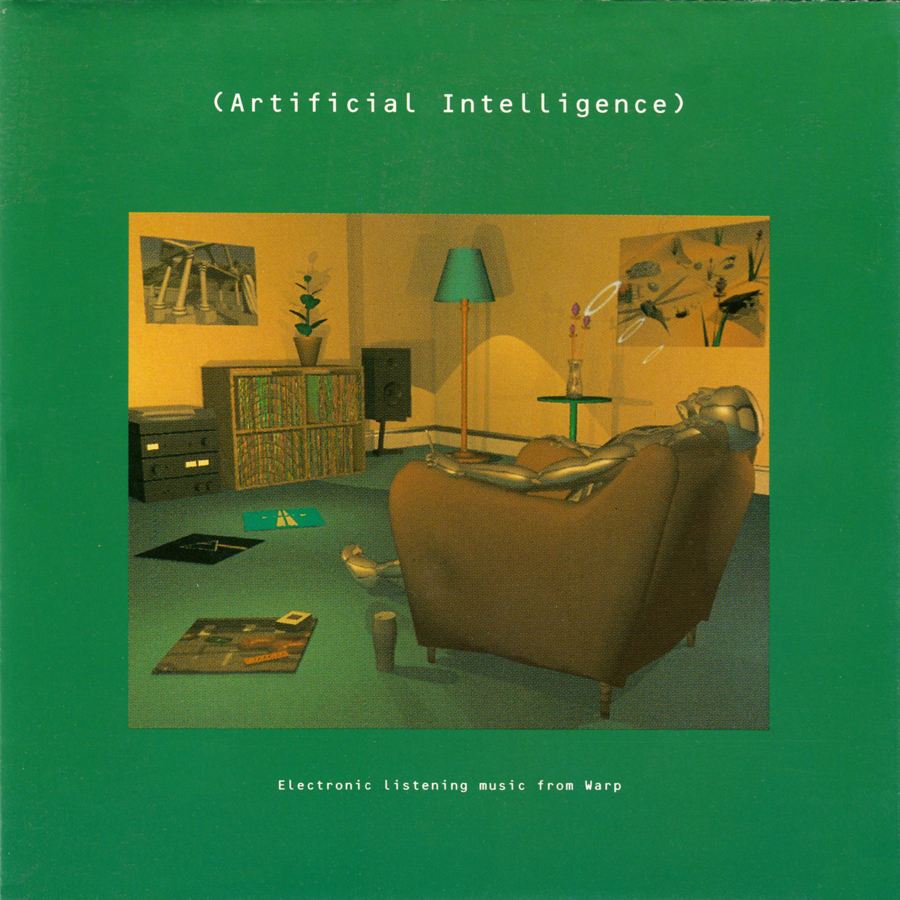

When Warp Records’ first Artificial Intelligence compilation was released in 1992, the label was little more than a bedroom outfit, its roster made up of virtually unknown artists. These were the twilight years of acid house, of ‘autonomous party zones’, warehouse raves and jam-packed solstice festivals. Artificial Intelligence, though, was a sedentary affair. Its fast tempo captured the ecstatic energy of dance tents but the beats were cut-up and disorienting, the samples obscured and mutated. This was music to listen to in solitude. The cover, an image of an android reclining on a living room chair, was accompanied by the sleeve note ‘Are you sitting comfortably?’ The album proceeds from video game bleeps to wide-panned Balearic pads on a journey from chaos to equilibrium, like a heart rate pulsing with amphetamines returning to normal after a big night out. The result is less about hedonistic excess than concentration – less about rave than its deconstruction.

Founded 30 years ago in Sheffield, Warp has grown into one of the world’s most respected independent record labels. When the UK’s underground party scene reached its zenith, the label didn’t just survive, it adapted to meet changing circumstances. Today rave culture is being canonized by artists and journalists alike in nostalgic terms as a kind of lost paradisal community. Jeremy Deller’s documentary Everybody In The Place (2019), Philly Adams and Kobi Prempeh’s co-curated exhibition ‘Sweet Harmony’ (2019) at the Saatchi Gallery, and Niall Griffiths’s novel Broken Ghost (2019) are just three recent celebrations of the divine, quasi-spiritual energy of those gatherings. Warp dissected that essence from the inside, long before it was being repackaged as history. At the very beginning of rave’s slow-motion collapse, they helped redeem the scene’s more intimate face, salvaging art from amid the ruins.

One thing that distinguishes Warp from its competitors is its refusal to succumb to nostalgia. The label is not stuck in an idealised past. It has grown and innovated, contributing greatly to the complexity and self-renewal of electronic music as a whole. Over three decades Warp has expanded across genres from jazz to folk and hip-hop, challenging the weight of their heritage without losing sight of it. Take the career of Richard D. James, aka Aphex Twin. His trajectory from ‘drill and bass’ into ambient soundscapes and most recently the non-western modes of 2014’s Syro exemplifies the extent of the label’s creative ambitions. Some critics have labelled such an approach IDM – Intelligent Dance Music – but this is a bit of a misnomer. James’s work is not the stuff of academic sound designers or snobbish audiophiles. Instead, his experimentalism is grounded in hardware-hacking, improvisation and an unashamedly punk attitude.

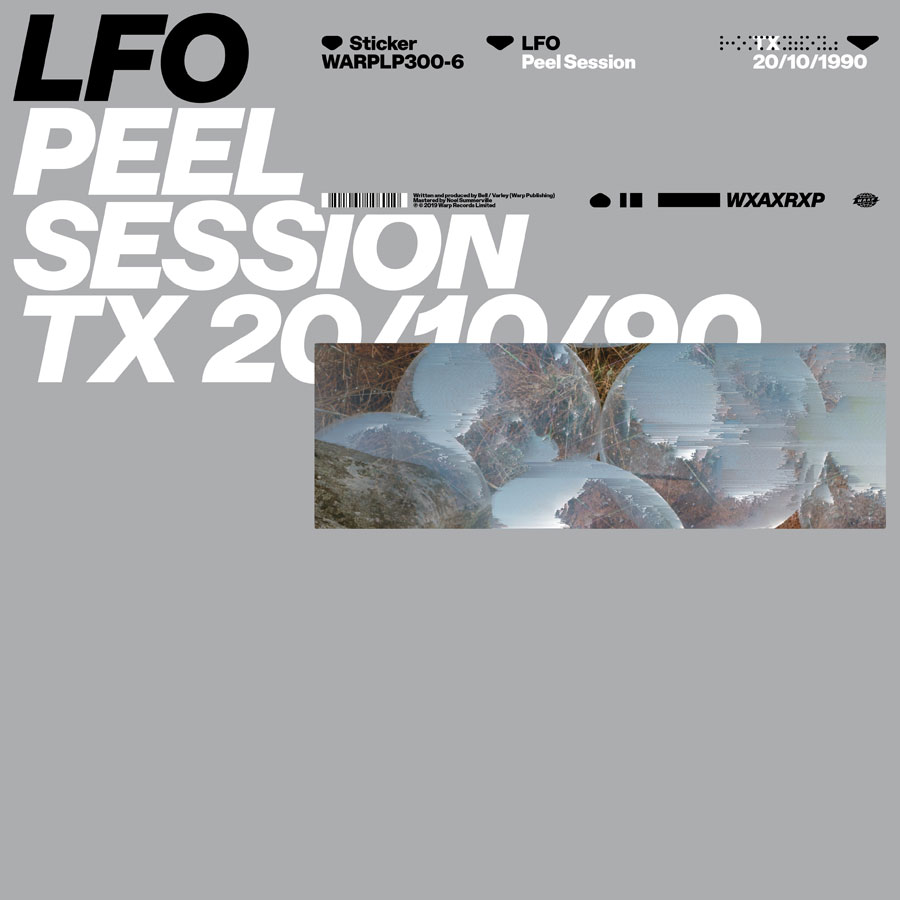

To mark their 30th anniversary Warp is releasing a box set of live performances with a heavy focus on the early years: Wxaxrxp Sessions (2019). John Peel mixes by LFO (1990), Seefeel (1994) and Plaid (1999) serve as fitting tributes to the anarchic creativity that fuelled the original Artificial Intelligence compilations. Fans of the Scottish duo Boards of Canada, meanwhile, will find an unreleased track, ‘XYZ’ (1998), which takes the opening bass tone from ‘Roygbiv’ (1996) and transforms it into a complex glitch pattern, reminiscent of their label-mate Squarepusher. Listening back, what’s particularly striking is the richness of the production values. Most of us have become used to static dynamics designed to make tracks listenable and loud on tinny phone and laptop speakers. These sessions, by contrast, use volume as an expressive tool. Texture comes and goes in waves, enveloping, as opposed to assaulting, the silence around it.

The collection would be an artefact for dedicated crate-diggers only if not for the representation of newer artists. The songs from the eponymous 2019 NTS radio session ‘Wxaxrxp’ demonstrate just how fearless the label has been in their signings over the years. Mount Kimbie divided Warp fans when they joined the label in 2012, sounding a little too ‘mainstream’ for some. The live performance of ‘You Look Certain (I'm Not So Sure)’ (2017), though, with its cleverly programmed guitar delay, subtle overdrive and clipped vocals, should convince even the most sceptical of critics that this is no mere ‘landfill indie’. The same might be said of Bibio. His renditions of ‘Haikuesque’ (2009) and a stripped-down ‘Petals’ (2015), remind the listener just how sensitive the label has become to melody in recent years. If post-rave is usually thought of in terms of strange rhythms and fast bpms, these songs reveal another, quieter, development within Warp, as a laboratory for ambitious pop.

The label’s ongoing commitment to the avant-garde is marked in two particular sets. A KCRW session from 2018 by Oneohtrix Point Never sees the artist play around with recent tracks ‘Love In The Time Of Lexapro’ (2018) and ‘Toys 2’ (2018), reducing them to their jazziest elements. The standout performance, though, is ‘Chrome Country’ (2013), which combines the vocal reverb and snappy snares of Nosaj Thing with the repetitive, piano-driven minimalism of Phillip Glass (led by one of the label’s latest signings, Kelly Moran). The New York-based multi-instrumentalist’s own session on Wxaxrxp Sessions is the only set yet to be broadcast and it happens to be one of the strongest. ‘Helix’ (2018) and ‘Love Birds’ (2019), are zen-like meditations, both of which utilize prepared piano, based around mesmerising repetitive cycles which slowly evolve in the mould of John Cage or Schoenberg. Gone are the comforting synths which feature across the rest of the boxset: this is classical music, with only the subtlest of nods to the eerie techno with which the label is most often associated.

Such commitment to quality across genres has made Warp a resilient force in the UK music scene. Bridging dubstep to atonal music – sometimes even fusing the two – is no small task. If they’ve succeeded, one suspects it’s due to the synergy between curators and musicians, a shared worldview and artistic dialogue that has enabled all parties to push themselves. This sense of community also serves as a rebuke to stereotypes that modern electronic music is isolated and fragmented. Think of the scene in Irvine Welsh’s novel Trainspotting (1993) where a grey-skinned Renton snarls at a girl listening to music through headphones. ‘Even though it’s supposed tae be a “personal stereo”, ah kin hear it quite clearly [...] ma eyes burrow intae the back ay her heid.’ This is a neat description of atomization in general. Warp, though, has defied that kind of logic from the beginning. Community, they seem to be suggesting, doesn’t just mean sweaty bodies in a crowd, it can thrive even in the decentred ways that we consume music today.

This is why it’s hard to really think of Warp as just a record label. Their work has always represented a broader cultural intervention. The iconic cover of Artificial Intelligence was a statement of intent, a visual manifesto designed to link-up armchairs and living rooms around the world. Aphex Twin’s …I Care Because You Do (1995), which shows a painting of the producer’s grinning face, was originally conceived to poke fun at the once-popular trend among techno DJs to hide their identities. Over the years it has come to encompass the label’s deviant side and its admirable capacity to laugh at itself. The latest boxset, with photographs by Ukrainian art collective Synchrodogs, plays instead on environmental concerns. Their Dada prints evoke a sci-fi, techno-pastoral fantasy of rocks and moss, disintegrating spray-painted trees and airy balloon-like structures. If Warp’s past is inseparable from post-industrial England, this new artwork represents their expansion to encompass experiments around an ever-more-connected and ecologically precarious world.

Warp was born against a backdrop of acid house but it has always offered something more self-reflexive and outward looking. Few other labels could claim to have cultivated such a coherent philosophy over the years: one which unites the pleasure of partying with its darker side, breaking down the false binary between nature and technology. Brian Eno’s Extinction Rebellion mix for Warp/NTS (2019) – which featured samples of Greta Thunberg – provided a rare glimpse of the politics latent in such ideas. While it didn’t make the boxset, this set was a good illustration of just how deeply embedded such assumptions are in the Warp culture, and how much more there is to this label than the mythologizing of old raves.

Main image: Weirdcore, Aphex Twin (detail), 2018. Courtesy: Warp Records