Was This the Decade that Fashion Fell Out of Fashion?

From normcore’s resurrection of the hoodie to gorpcore’s luxe ‘into the woods’ aesthetic

From normcore’s resurrection of the hoodie to gorpcore’s luxe ‘into the woods’ aesthetic

Indulge me, if you will, and cast your minds back to simpler times. The year is 2010. A new photo-sharing app called Instagram launches. The year’s big sellers are jeans so skinny they have become jeggings. And the problematic Sex and the City 2 is released in cinemas, signalling the downfall of the Manhattan foursome who had defined a certain type of aspirational dressing at the turn of the millennium. Fast forward to 2019 and a reality-television star is president of America, the prosaic puffer jacket is topping bestseller lists and mock funerals are being staged at London Fashion Week to protest the industry’s role in the climate crisis. As I ruminate on the state of style at the threshold of a new decade, I can’t help but wonder: were the 2010s the decade that fashion fell out of fashion?

This anti-fashion sentiment is not just felt through Extinction Rebellion urging the public to boycott the sector on account of its vastly damaging environmental impact, but also in our style choices. Anti-fashion made headlines after the 2013 publication of a report by New York-based trend-forecasting group K-HOLE, which outlined the rise of normcore. In its original incarnation, normcore was not a style but a philosophy. ‘Individuality was once the path to personal freedom – a way to lead life on your own terms,’ the report read. ‘Normcore seeks the freedom that comes with non-exclusivity. It finds liberation in being nothing special and realizes that adaptability leads to belonging. Normcore is a path to a more peaceful life.’ As translated on the streets, this unbearable lightness of belonging was distilled to New Balance trainers, Crocs, Patagonia windbreakers, Birkenstocks, turtlenecks and hoodies. Moodboards featured comedian Jerry Seinfeld and Apple CEO Steve Jobs wearing what Alex Williams described, in a 2014 New York Times article, as ‘bland, suburban, anti-fashion attire’.

The resurrection of the hoodie had particular significance in the UK. The hoodie-wearing teenager had become a folk devil during the mid-2000s, banned from shopping centres and associated with antisocial behaviour. In 2006, Conservative politician David Cameron, then leader of the opposition, tried to address this prejudice in a move that was dubbed ‘hug a hoodie’ by the Labour government. Moral panic over the item came to a head in the wake of riots that broke out following the shooting of Mark Duggan by police in 2011, the reporting of which had a perniciously racialized tone. The repackaging of the hoodie as part of the normcore wardrobe – which saw it catapulted from anti-social teen to Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg – demonstrated how fast sartorial semiotics can evolve, or at least how context can neutralize perceived threat.

The link with Silicon Valley is undeniably a key part of the appeal. The tech industry has redefined what we think of workwear over the past decade, and the results have seeped into the high street and high fashion. Buoyed by other success stories of the decade, such as athleisure and streetwear, hoodies found their way onto the catwalk with Kanye West’s Yeezy debut in 2015 and Vetements’s first catwalk show the same year.

In 2016, with calamitous votes in the UK and US respectively resulting in Brexit and the election of President Donald Trump, politics came to the fore again in fashion. Normcore mutated into gorpcore, named for the American term for hiking-trail mix, with a focus on outdoor adventure. The Cut outlined this progression in 2017: ‘Where normcore idealized the Mall, indiscriminately incorporating bland stylistic totems across suburban categories [...] this new aesthetic worships the Woods, strictly defining itself by the idioms of hiking-camping-outdoor apparel. It telegraphs an enlightenment beyond urban, bourgeois concerns: I can survive perfectly fine outside of the city – and in style, thank you.’ If normcore is Jobs’s turtleneck or Zuckerberg’s hoodie, gorpcore is Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos in a puffer vest.

The Cut’s breakdown of gorpcore focused on the anti-fashion kudos of performance brands such as Arc’teryx, Columbia, Patagonia, Teva and The North Face. The Patagonia fleece took on renewed significance in light of the company’s laudable record on environmental policies and ongoing outspoken resistance to the Trump administration, including suing the President over plans to reduce Bears Ears National Monument and donating the US$10 million it saved from Trump’s corporate tax cuts to organizations fighting the climate crisis. They also encourage longevity with a robust repairs policy. Wearing Patagonia not only signals a love of the great outdoors and ecological awareness; it demonstrates a clear political allegiance.

The rapidly increasing success of outdoor brands mirrors the population shift towards the countryside, as rising living costs drive people out of urban centres. In the long shadow of the financial crisis, activities such as hiking and wild swimming are also on the rise. Once appropriate equipment has been purchased, these activities are broadly free, reportedly good for mental health and Instagram-friendly.

As sales of endurance wear grow, fashion brands circle overhead. Comme des Garcons (F/W 2018), Supreme (S/S 2018) and Junya Watanabe (F/W 2017) have all collaborated with The North Face. At New York Fashion Week in 2017, A$AP Rocky was spotted in a Balenciaga puffer jacket and Calvin Klein fleece. Meanwhile Drake’s video for ‘Hotline Bling’ (2015) caused a spike in sales for luxury ski-wear brand Moncler. Moncler’s well-documented fashion strategy has extended to flamboyant puffer gowns designed by Pierpaolo Piccioli, creative director at Valentino. Concurrently, Japanese brands such as Snow Peak and Mountain Research sell increasingly luxe versions of gorpcore for those who appreciate the aesthetic without, necessarily, the action. As a Mountain Research representative told The New York Times earlier this year: ‘We don’t do any fishing ourselves, but we love the fishing men with their crazy pockets.’

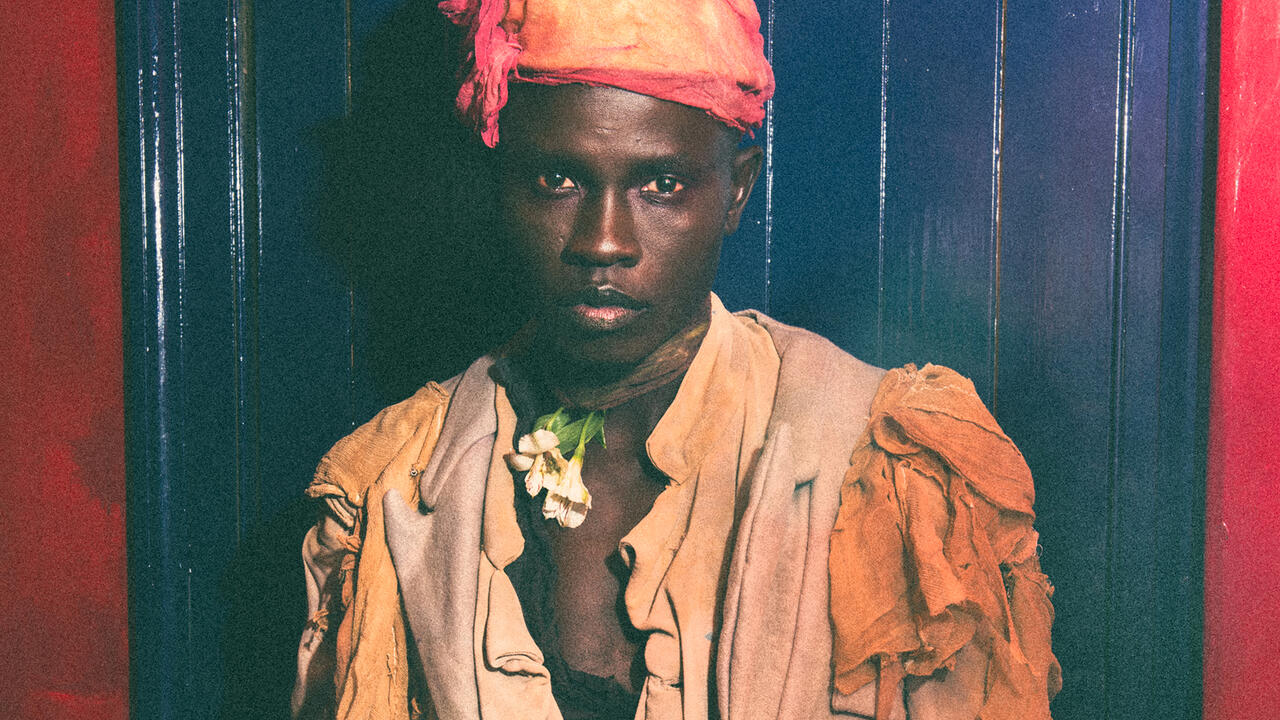

In 2018, a cataclysmic UN climate report gave the world just over a decade to limit emissions and get climate change under control. The same year, Extinction Rebellion was formed as a ‘non-violent civil disobedience movement’ to force governments into action to avoid catastrophe. The fashion industry responded with warcore: dressing for impending societal breakdown in extreme military styles tailored for civilian use. The look has been linked to the influence of Virgil Abloh at Off-White and Louis Vuitton, and includes hints of ultraviolence in the form of balaclavas, flak jackets and face masks, occasionally accessorized with a riot shield. This is still status dressing but with a particularly apocalyptic angle, like sartorial disaster capitalism on ketamine.

Faced with the possibility of climate catastrophe, protective clothing that helps shield against extremes of weather has gained new currency. But people are also demanding ethical and environmental change within the sector. This decade saw the formation of the global non-profit Fashion Revolution, which campaigns for such reform. It was founded in 2013, in response to the Rana Plaza factory disaster in Bangladesh, which claimed more than 1,000 lives. Extinction Rebellion are urging us to boycott the fashion industry and focus on the ethical and environmental impact of the things we consume. Secondhand style is encouraged as a more sustainable option, and researchers are suggesting that, within a decade, this market will outstrip fast fashion, reaching a value of US$64 billion. Even mass-market companies like H&M are rethinking traditional retail models by offering customers the option to hire clothes.

The internet continues to shape our style. Instagram, which in fewer than ten years has accrued at least one billion active users, has become a platform for call-out culture, ensuring fashion criticism today can help to hold the industry to account. In 2010, smart fashion was one of the biggest stories. As the decade closes, however, this has morphed into virtual fashion – proving that, along with deep fakes, reality online is relative. It’s all part of our conscious uncoupling with the concept of truth.

It’s no secret that fashion runs in cycles, or that the way we dress can be political. But this decade we have witnessed a particularly toxic Ouroboros. Politics became fashion (slogan T-shirts, commodity feminism, Women’s March Pussy Hats on the catwalk), while sectors of the industry embraced anti-fashion, churning out derivatives of workaday pieces such as the fluro vest, the originals of which became political. Black is no longer ‘the new black’; rather, it’s the colour of protest – from the Time’s Up movement against sexual harassment to pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong (where it’s been rumoured that imports of black clothing have been banned). White became a colour of solidarity for supporters of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton during the 2016 US election, while the streets of Paris convulsed with the acidic yellow of the gilets jaunes movement for economic justice.

In a decade dealing with the aftermath of the financial crisis, ostentatious conspicuous consumption fell from favour. The aesthetics of luxury shifted. Yoga wear became aspirational. The DHL T-shirt by Vetements, a design collective headed by Demna Gvasalia (now creative director at Balenciaga), sold out at a price point of GB£185, despite being almost indistinguishable from the DHL company’s own T-shirt. The irony of anti-fashion has replaced more obvious markers of wealth. Basics like the fleece jacket indicate social, political and environmental awareness. Above all, the simple puffer vest most succinctly tells the story of the 2010s. The down-filled garment acts as armour for DeRay Mckesson’s Patagonia-clad activism for Black Lives Matter, but has simultaneously become a uniform for the one percent with Brunello Cucinelli designs selling for upwards of US$1,000. Nothing more perfectly symbolizes the escalating inequality and political divisions that have ultimately defined this disastrous decade.

‘The Hoodie’, an exhibition which considers the garment as a socio-political carrier, is on display at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam, until 12 April 2020.

Main image: Extinction Rebellion, 2019, London Fashion Week. Courtesy: Extinction Rebellion; photograph: Ben Darlington