What Can't Be Seen

Five young artists exploring queerness, disability, the standardization of bodies and the politics of visibility

Five young artists exploring queerness, disability, the standardization of bodies and the politics of visibility

I live close to a centre for developmentally disabled adults. Recently, I found myself standing at a street crossing beside a middle-aged woman. When the light turned red, the woman tapped my arm and said, with urgency: ‘Walk with me. Walk with me.’ She held out her hand. All the threats and scams I’ve witnessed in city life shot through my mind, but then the woman looked so frightened; I took her soft, crêpey hand and held it as we crossed the street. This intimacy felt uncomfortable and startlingly human. When we reached the curb, the woman let go and walked on. It was like having a one-night stand that left me wanting more than this brief experience of a life where touching a stranger is no big deal.

In his book Crip Theory (2006), Robert McRuer argues for ‘the desirability of a loss of composure, since it is only in such a state that heteronormativity might be questioned or resisted and that new (queer/disabled) identities and communities might be imagined’.1 But shifting the public imagination is no easy feat. Chicago-based artist Riva Lehrer – who makes portraits of disabled artists, writers and performers – has found that the mere presence of an impairment threatens to consume a work. When she was in art school, Lehrer, who was born with spina bifida, was discouraged from making self-portraits. She was bluntly told that her body was not an acceptable one for portraiture. It wasn’t until she was in her 30s and met a group of disabled activists that Lehrer dared to focus on disabled bodies. In her 2015 TED talk, ‘Valuable Bodies’, she discusses the difficulty she’s had in getting abled audiences to see expressions of love or happiness or grace in her work. ‘People think that pain is the essential nature of the disabled body, that disabled pain is permanent, that it is the truest thing about us and that we cannot be rescued. So there’s no exit from pain for the subject or for the viewer.’2 While Lehrer doesn’t strive to be a political artist, she’s found that ‘any depiction of a disabled person at this time is embedded in politics’.3 The tenderness of Lehrer’s gaze, her willingness to resonate with people who have been told their bodies are unacceptable, shouldn’t be a radical gesture. Yet – despite decades of activism and theorizing – it still is.

Wanting to avoid such frustrations as Lehrer has endured, younger artists Zach Blas, Andrea Crespo, Park McArthur, Patrick Staff and Christine Sun Kim have developed strategies to explore queerness and disability while subverting the transparency of identity politics and the preconceptions audiences might impose upon them. At times, their work thwarts identification and understanding; at others, it is aggressively blatant. This friction between legibility and impenetrability creates a charge that I find exciting.

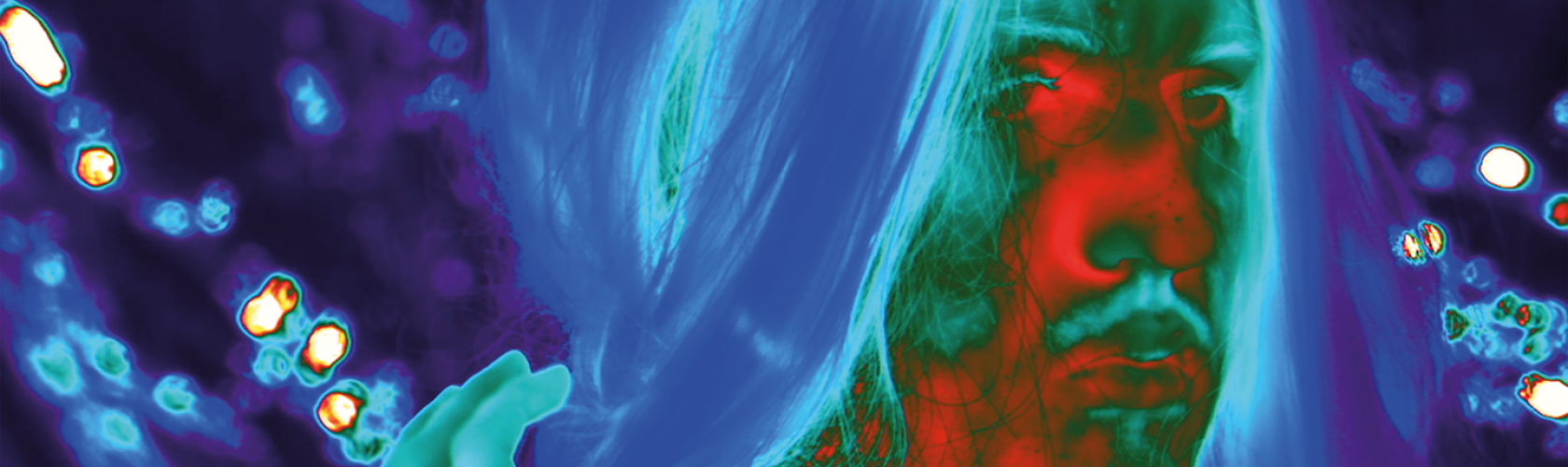

Zach Blas’s work with biometrics critiques the violence of a normative gaze. Global standards of identification programmed into capture technologies, such as fingerprint or retinal scanners, according to Blas, ‘insidiously return us to the ableist, classist, homophobic, racist, sexist and transphobic scientific endeavours of the 19th century’.4 Facial recognition programmes cannot perceive dark skin, while blink detection software reads an Asian woman as closing her eyes when she isn’t. Wheelchairs, skin diseases and visual impairments can also cause biometric failures. Inspired by philosopher Édouard Glissant, Blas champions opacity as a means of resistance against dominant and state-controlled forms of representation and visibility. According to Glissant, the imperialist gaze obscures or ignores otherness, making the world conform to Western Enlightenment ideals. Thus, for Glissant, opacity is not obscurity; it is resistance to erasure. In Poetics of Relation (1997), the philosopher argues for ‘the right to opacity that is not enclosure within an impenetrable autarchy but subsistence within an irreducible singularity. Opacities can co-exist and converge, weaving fabrics.’ Insisting on our own fundamental opacity does not close us off from others, or mire the self in solipsism: rather, it is an acceptance of the unique core of difference and particularity each of us carries within. There is no standard self to be known.

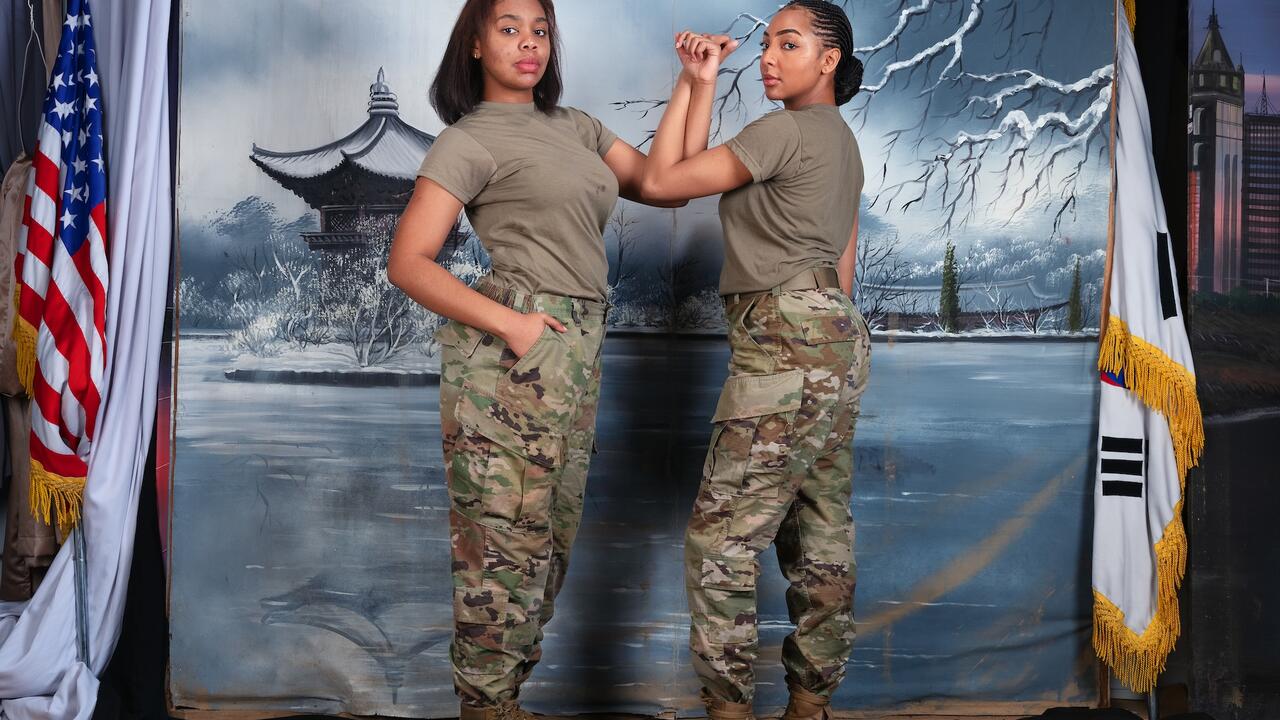

For surveillance culture, opacity is the ultimate F-you. In his ‘Facial Weaponization Suite’ (2011–14), Blas uses the standard templates of biometrics against themselves, scanning the faces of a group of people to create a series of composite masks that look formless and inhuman. One of these masks, Fag Face (2012), comprises aggregate data from many queer men’s faces, resulting in a pink blob that is unreadable to facial recognition software. The mask is both comic and frightening; it looks like the victim of some terrible nuclear experiment in a 1950s sci-fi movie. The artist’s series of ‘Face Cages’ (2013–16), however, has a terrifying beauty. Blas scanned the faces of four queer artists and made metal masks for each of them out of the resultant diagrams. Even though the diagrams are supposedly perfect, the masks don’t really fit and are so painful that to wear the standardized gaze becomes an endurance performance.

While the body is not visibly rendered in New York-based artist Park McArthur’s work, its traces are everywhere in her installations: displaced onto environments, clothing and objects involved in her daily care. (McArthur preferred that this article be published without visual representation of the works mentioned.) In a 2014 series of ‘commodes’, the artist’s worn pyjama bottoms, the uniform of the sick, hang from stainless-steel stands. The work speaks of absence and intimacy, of disconcerting exposure. In During the month of August ESSEX STREET will be closed (2013), clothes (some of them McArthur’s own) were hung outside the eponymous New York gallery from chains and hosed with water once daily. The horrible vulnerability of the clothes reaches beyond McArthur’s life, pointing to histories of abuse of the disabled. McArthur changed the address signage of the gallery to 1918 1st Avenue, an abandoned nurse’s residence and training school located near to where Frieze Art Fair is held, ironically suggesting the art world’s myopia in relation to vulnerable bodies, regardless of their proximity.

For Ramps (2010–14), 20 ramps were placed on the gallery floor, most of them borrowed from museums and galleries McArthur had visited. A sign was displayed at each lending institution, declaring ‘RAMP ACCESS LOCATED AT ESSEX STREET’. The artist’s caustic humour suggests an underbelly of rage. It is impossible to reduce the ramps to abstract symbols of accessibility: each bears the marks of hundreds of specific negotiations. They are chipped and dirty and, if you were to touch them, they would probably give you splinters. They speak of ongoing obstacles in assuring accessibility, how McArthur’s personal challenges mirror larger social issues.

Christine Sun Kim, who was born deaf, became interested in working with sound due to her encounters with ‘sound etiquette’: all the ways she had to learn to not make noises that would disturb the hearing. Don’t bang your fork against a plate. Don’t make belly laughs in a cinema. In other words, she was encouraged to become quieter, less noticeable – to fade into the background. Kim’s 2015 TED talk, ‘The Enchanting Music of Sign Language’, has been viewed online more than a million times. Chipper, with blue ombre hair, Kim positions herself as an ambassador to the hearing, projecting that, yes, understanding is possible. People love this message, perhaps because she doesn’t seem angry. Photos from her performances reveal audiences beaming with huge, enthused smiles. Kim offers an upbeat, thought-provoking experience. She places herself so comfortably in the centre of her work that it’s easy to forget it isn’t about her as an autobiographical subject. It’s about sound, language and perception – abstract material that never feels bloodless in Kim’s hands. No matter how intimate her engagement with her viewers, Kim maintains her fundamental opacity: she never seems consumed by their gaze.

In her performance Face Opera ii (2013), the artist and a group of deaf people, arranged as a choir, act out emotional content without the use of their hands, forming a moving sculpture that sways and startles. There is a comic, creepy loopiness to the performance, an addictive lack of self-consciousness. I can’t stop looking at her ‘Upside Down Noon’ drawings (2014), which combine musical notation with gestures from sign language – synaesthetic slippages that are consistently graceful, witty and smart.

As Blas contests standardized bodies, artist Andrea Crespo, in the roundtable discussion‘GenderFluidityandPost-Identity’, rails against standardized identities, including ‘LGBT/Queer® and its genderist doctrines’.5 In the same debate, Crespo goes on to describe the alternative possibilities they imagine, beyond the scope of queer or identity politics: ‘To reiterate, the futurities we are interested in aren’t queer. We are more interested in teratological and machinic futurities that are beyond the scope of the popular queer imaginary but nevertheless imminent. An autistic or machinic aesthetic rather than a queer aesthetic.’ Crespo has found community in online micro subcultures, such as the social media platform DeviantArt, where the erotics of neurological divergence are embraced. The fluidity of online avatars provides a means of connecting for those for whom connecting is otherwise not possible – those suffering from mental illness or who, like Crespo, are on the autism spectrum. Much of Crespo’s art centres around a pair of manga-inspired conjoined twins, Cynthia and Celinde, who are sometimes drawn holding each other in a sensual hug. When considering who they are, the pair say: ‘We may be changelings, but we’re no stand-ins.’ The twins, who sometimes have three legs and long undulating toes, resist classification. They are simultaneously cute and grotesque, self-absorbed and seductive, pointing to radical desires that have yet to be defined. Crespo’s refusal of preconceived queer categories proposes that even a progressive gaze can reduce persons to the violating transparency Glissant warns against. Their art is a tribute to the mystery of identity, reminding us that the self is even more otherworldly than we fear it is.

Patrick Staff uses installation, dance and performance to explore how subjectivity is constructed and deconstructed, and to question, according to Gil Leung in a 2014 interview with the artist, ‘which bodies [...] are abled and disabled, legitimate and illegitimate’.6 In ‘Scaffold See Scaffold’ (2013–14), Staff investigated chronic illness and labour, amongst other topics. Their process involved research in the Trinity Laban dance school archives and a series of discussions and workshops with a wide range of people, including practitioners and activists, artists, older queers and a young performance group. Staff made a series of three billboards showing the transcription of an interview he conducted with a disabled collaborator, which were displayed on the exterior of The Showroom gallery’s building in London. The anonymous interviewee admits to not being knowledge-able about disability theory, and Staff assures her that’s fine. A recurring topic is how her disability has shifted her self-definition. She also covers survival difficulties, bureaucracy, strategies for conserving energy. It has taken her years to shift from hiding her illness to being open about it. Imagining her confusion and shame blown up big enough to fill the side of a building, I feel a pang of exposure that is unbearable. But the more I ponder the interview and billboards, the more the interviewee eludes me. She is tentative and ambivalent, at times contradictory. The interview is incomplete, comprised of time-stamped excerpts. Portions are labelled as redacted. As if to further emphasize the incompleteness of the text, Staff has inserted various graphic disruptions. Column-wide wavy lines suggest section breaks, but the rationale behind their placement is obscure. Most of the third column of each page is slashed by a series of short parallel lines that descend at an angle. The artist is setting up a tension between exposure and concealment. We witness this woman’s vulnerability, but we never own it. Like Glissant, Staff is suggesting that we can exist in solidarity with one another only by accepting our impenetrable differences.

Staff is currently working on another piece exploring illness and exposure, a commission for the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, due to open this spring. It is based on artist Catherine Lord’s memoir, The Summer of Her Baldness (2004). The titular protagonist, Her Baldness, is an alter-ego who emerged when Lord underwent chemotherapy for breast cancer. Her Baldness sent out messages to a closed list of email contacts, thereby keeping Lord connected to her friends, and allowing her to both reveal herself and to maintain her opacity.

For the cover art to her 2011 book, Cruel Optimism, theorist Lauren Berlant chose Lehrer’s Riva and Zora in Middle Age (2005). It is a painting of the artist and her dog, who is blind in one eye and wearing a vivid white cone around its neck. Lehrer is lying on the ground behind the dog, her hands covering her face. What Berlant writes of Lehrer’s painting could be said of all the work discussed here: ‘mortality and vulnerability hover as the velvet uncanny of the situation’. These artists pull the rug out from under simple aesthetic appreciation – from compassion even. In this destabilized state, new possibilities of relation can occur.

1 Robert McRuer, Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability, 2006, New York University Press

2 Riva Lehrer, ‘Valuable Bodies’, 2015, tinyurl.com/gvd6yu6

3 Kathie Bergquist, ‘Meet a Ms. Fit: artist Riva Lehrer’, Ms. Fit, 2013, tinyurl.com/gvpzz7k

4 Zach Blas, ‘Informatic Opacity’, Journal of Aesthetics and Protest, 2014, issue 9

5 Andrea Crespo from a roundtable conversation with Telfar Clemens, Harry Dodge, Amos Mac and A.L. Steiner, Kaleidoscope, 2015, issue 25

6 ‘A Structural IdeaofFluidity’,PatrickStaffinterviewwith Gil Leung, Mousse 45, October 2014