What a ‘Slow Look’ at Pierre Bonnard’s Harmonic, Memory-Drenched Paintings Reveals

Tate Modern is encouraging visitors to slow down at its major exhibition of the French Post-Impressionist painter

Tate Modern is encouraging visitors to slow down at its major exhibition of the French Post-Impressionist painter

A surprising double portrait greets visitors to ‘Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory’ at Tate Modern. Young Women in the Garden (1921–3/1945–6) depicts two women facing each other: one is Bonnard’s lover Renée Monchaty, the other is his wife, Marthe de Méligny. Dense with pigment, the figures are painted, reworked and then painted over again. In the many years Bonnard took to complete the work, it’s as if he was looking for something with his line. It’s a painting concerned more with process than framed result.

Young Women in the Garden is also a misfit: painted over 25 years, it doesn’t fall neatly into the exhibition’s chronological story. Instead, it’s tacked to the front, in the very first room. Cropped unusually, with de Mélgny only partially in view, the back of a chair looms large in the foreground. It looks as if it was composed from one of the intimate snapshots that appear later in the exhibition, yet it’s painted from memory, in years’ worth of staggered efforts. ‘I leave it … I come back … I do not let myself become absorbed by the object’, Bonnard quips. Although the painting is an acute case of the artist’s leisurely pace, it is one of several works in the exhibition that took years to complete.

Applying this logic to their own practice, Tate curators are encouraging visitors to the exhibition to attempt ‘slow looking’ – Arts Council-style-speak for spending extended periods of time with works of art. Tate have also scheduled a programme of related events including ‘slow looking’ tours around the 13-room exhibition, one led by Rebecca Chamberlain, a Goldsmiths lecturer in neuroscience and the perception of art, and another by Matthew Gale, Head of Displays, on 11 March and 11 February respectively. To complete the experience, Tate will celebrate international ‘Slow Art Day’ on 6 April.

Bonnard’s works are ‘so dense that you can return to them again and again and see new things’, says Gale. Anecdotally, this is true: it took me two visits (and scrolling through photographs on my phone) to notice a third figure, reflected in a window pane in The Dining Room, Vernon (c.1925). But of course, there’s more to Gale’s method than a ‘spot the difference’ approach to viewing art. Bonnard’s paintings offer pleasurable reward for patient looking. Studying Nude in an Interior (c.1935), for instance, is a harmonic experience: the orange wallpaper, a sliver of a standing purple nude, a fuchsia bathtub, the mint dresser. Round and around your eye can turn. A state of meditation, it seems, cannot be reached in 17 seconds – the average time, according to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, that a visitor spends with a single piece.

Tate’s show of around 100 paintings, photographs and unframed works on canvas marks the first major UK exhibition of Bonnard’s work in 20 years. The ‘slow looking’ framework helps visitors reconsider a painter working in 20th-century, war-torn France in the modern era. But why now? The exhibition’s text explains that critics from Bonnard’s own era knew him as a ‘painter of happiness’; ‘the colourful seduction of [his] work was seen as a message of hope’. In our own time too, we might be tempted to think of Bonnard as a painter of escapism: viewing his domestic scenes offers respite from the fraught political present. After all, Millennials, it was recently reported, are using art institutions to de-stress from the pressures of modern life.

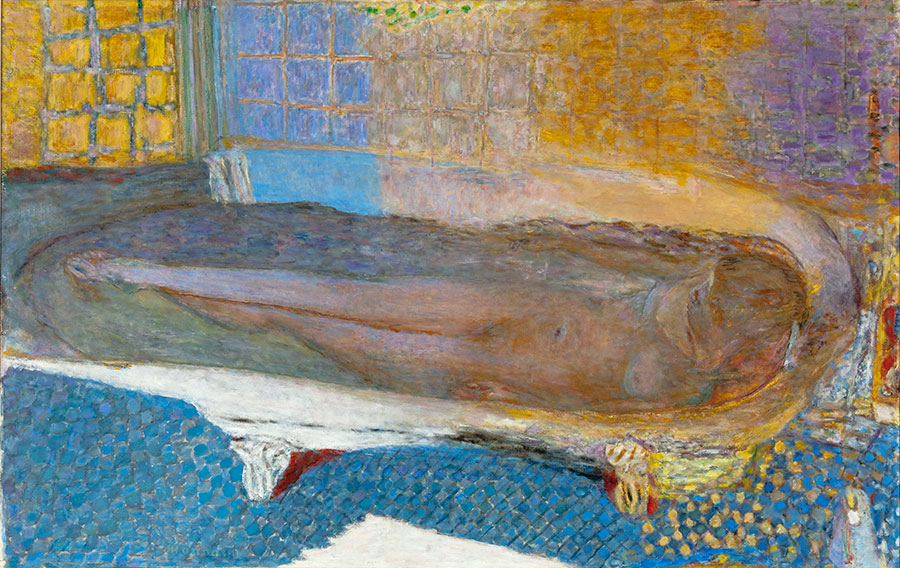

On a series of narrow canvases toward the end of the exhibition, Marthe de Méligny lies supine in a bath. In one, (Nude in the Bath, 1936), her upper body melts, Klimt-like, into orange chequered tiles; you can almost feel the steam. And yet the painting, the text reminds us, is one of illness. De Méligny suffered from poor health, and was prescribed hydrotherapy through repeated bathing to treat her various ailments. Nude in the Bath is not a painting to transport you to a state of tranquil repose; it’s a melancholy portrait of a woman struggling to get herself well. Looking at Bonnard’s paintings, then, is not to retreat from the present. Rather, like meditation, his works encourage awareness and acceptance of the everyday.

As a policy, ‘slow looking’ is at the confluence of old and new schools of thought of what a museum is for: solitary contemplation meets participatory action. Crucially, the exhibition takes historic paintings and puts them to use by reframing them as objects to soothe a stressed society. Of course, there are other – perhaps more urgent – ways museums can serve their communities: read Laura Raicovich, for example, on how arts institutions should step up and serve marginalized people.

But how much should we expect of an exhibition? In The Studio with Mimosa (1939–46), a final work in the show, as well as Bonnard’s life – he died in 1947 – plumes of yellow mimosa blossoms are set against lime green grass and a hot orange interior. Prompted by what he called the ‘first emotion’ of the natural scene, it thrills you into the present. While ‘Pierre Bonnard: The Colour of Memory’ might not be a cure-all for an anxious population, it does set aside a space for a screen-fried precariat to stop, breathe and admire the view.

Main image: Pierre Bonnard, Coffee, 1915, oil on canvas, 0.7 x 1.1 m. Courtesy: Tate, London