What’s Behind the Voluptuous Horror of Kembra Pfahler?

The provocative New York performance artist talks about her influences – from surfing to Jack Smith

The provocative New York performance artist talks about her influences – from surfing to Jack Smith

Amy Sherlock When did you know you wanted to be an artist?

Kembra Pfahler I grew up in the 1960s in Hermosa Beach, California – a golden South Bay surfer city. My father, Freddy Pfahler, was a legendary surfer who was in Bruce Brown documentaries, including The Endless Summer (1966) and Slippery When Wet (1958). It was an idyllic time, when surfing was our American Renaissance and the lights of consciousness were being turned on. There was so much ritual, mythology and non-traditional religious custom in my life – like getting up at 5am with my father to watch the tide.

AS What did you mother do?

KP My mother, Judy Ball, is also an artistic person. She had me when she was just 18 years old. Every night, she would sit on my bed and take my hand and say: ‘I love you. You’re an artist. You’re going to grow up to be a very creative woman.’ Like many people, I experienced a lot of violence and chaos in my life as well as all that love but, underlyingly, I was a lucky kid growing up in that era right on the beach.

My earliest influence was probably the SS Dominator, which was shipwrecked in Palos Verdes in 1961. All of the surf kids were obsessed with it and, every day, we would pedal our bicycles down there. To the right of the shipwreck was Malibu. In our child consciousness, it was heaven – bigger waves, more interesting people, a scarier life.

AS So, you were on the beach every day?

KP Yes, we were always just in bikinis. We’d put on our clothes to go see films, but we didn’t wear shoes – kids from the beach never wore shoes. I remember the sticky floors on my bare feet, my face hot and sunburnt, going into Grauman’s Chinese Theatre in L.A. to see a film – it was my idea of heaven on earth.

When my parents divorced, my stepfather, Larry Ball, moved in with us. He was a poet from Detroit and his record collection included Parliament Funkadelic and Bootsy Collins, his books were mind-bendingly interesting and he had pillowcases filled with marijuana. It was part of the culture at the time for young kids to take the same drugs as their parents, for all of us to be in a state of obliteration, driving towards higher consciousness.

My childhood is a source of inspiration that still lifts my spirits. I meditate saying the names of those places – Dominator, Redondo, Hermosa, Pacific Palisades, Malibu – and I feel the warmth in my heart.

AS Why did you move to New York?

KP I kept getting thrown out of school. I was a teenage goth, I dyed my hair from a young age and I liked the dark women of horror. My aunt was a casting director for horror movies – she had worked with Kathryn Bigelow and Stephen King – and one of her best friends, an English lady called Rita, said to me: ‘Kembra, why don’t you come over to my house and draw.’ So, I did that for a couple of years and prepared my drawing portfolio for New York’s School of Visual Arts. I was accepted when I was in 11th grade: I didn’t even finish high school.

AS When did you start doing performance rather than drawing?

KP The performance came about because I was living in apartments that had literally nothing in them. I had my body to work with and that was it.

AS Who were your teachers?

KP Mary Heilmann, Lorraine O’Grady – in fact, I was in a performance this year with Lorraine, Laurie Anderson and Anohni at The Kitchen in New York called She Who Saw Beautiful Things. It was dedicated to the late Japanese trans performer Dr Julia, who played with Anohni and the Johnsons. And, in 2008, my work was shown alongside Mary Heilmann’s at the Whitney Biennial. I’ve been incredibly lucky to work with some of my favourite teachers and artists. I didn’t care for Joseph Kosuth, though. He once screamed at me: ‘Kembra, what are you?’ At first, I turned away, because his words really hurt me. Then I looked him in the eye and said: ‘I’m an availabilist. I make the best use of what’s available.’ Sometimes, anger can point you in a direction, and that’s what happened to me that day. I invented availabilism because he enraged me.

AS A lot of your work now is about gender politics. Did anyone specific shape your thinking around that?

KP My first husband, Samoa Moriki. When I first saw him, he was dancing on the bar at the Pyramid Club in the East Village. We were married and worked together for 21 years. He was from Hiroshima and adored Japanese theatre: Butoh, Noh and playwrights like Yukio Mishima. But he especially loved extreme outside performances, in which people would dive from the sky into pools of water: physically courageous, beautiful acts. Samoa appeared at one of the first Wigstock drag festivals with Lady Bunny and collaborated with the great performance artist Tanya Ransom, who sadly died of AIDS. Ransom was queer but had a child with a woman called Paula Swede. At the time, many of us were gender fluid and simply didn’t talk about it: the language was only just being born. Later, important people like Ron Athey, Bruce LaBruce and Vaginal Creme Davis would articulate it.

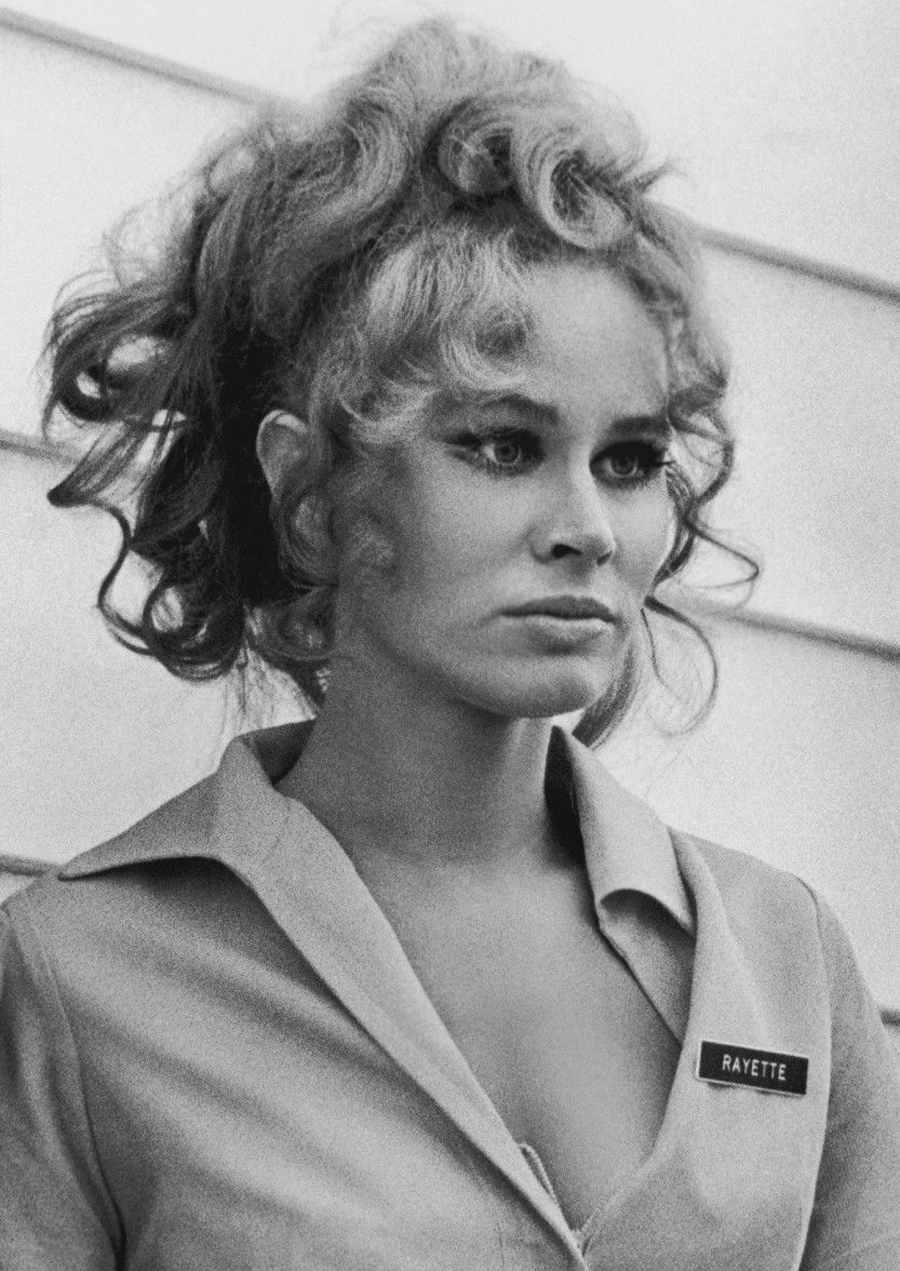

AS In 1990, you formed a band with Samoa called The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black. What’s the story behind the name?

KP I loved all of Karen Black’s films: she was somehow beautiful yet ugly, and her consciousness was so expanded. One day, Mike Kuchar, the underground filmmaker, said to me: ‘Oh, Kembra: your work looks voluptuously horrific.’ And that’s how the name started. Karen Black actually came to the band’s first L.A. performance, in 1991, and introduced us saying: ‘I’m not sure if this is meant to be an insult or an homage: does voluptuous mean I’m curvy or fat?’ Then she took my hand and said: ‘You’re an artist and this is a creative project.’ She never sued me; she just let me be an artist.

AS Recently, you’ve been working on a project called Future Feminism.

KP Anohni, Johanna Constantine, CocoRosie and myself launched Future Feminism in 2014. It stemmed from a desire to speak with one another about our practices without a sense of hierarchy. We do not make decisions based on a majority: we continue our discussions until we reach a consensus. It takes much longer and changes your perception of time. It’s been one of the greatest yet most difficult experiments of my life.

Tragically, Ashley Mead, an incredible artist and one of our interns on the 2014 ‘Future Feminism’ exhibition, was murdered by her boyfriend shortly after the show. She was only in her early 20s and had a daughter.

AS Oh my God: that’s horrendous.

KP Our 2017 exhibition in Aarhus was focused on sharing Ashley’s story: we wanted to create a narrative about her life that wasn’t entirely tragic. Ashley was one of the young people in the group who kept us all together, reminded us of our priorities. She was a great influence on me – even though I was 53 at the time – because she taught me about patience, sacrifice and open-mindedness; she taught me about sharing, love and joy. She was the foundation for Future Feminism.

Johanna made a sculpture in which Ashley’s beautiful body – which had been brutally dismembered – was, symbolically, put back together. The local people helped us build a boat where we held a moonlit ceremony for Ashley. We wanted to celebrate her life rather than focus on the tragedy.

AS Your work has always been very collaborative.

KP I do feel the need for community and I believe the greatest changes are wrought through open-mindedness and grassroots activism – the principles of which are still the most vital to me. Important as it is to collaborate and meet others, though, I still spend a great deal of time isolating myself, instinctively protecting this painful humanity. But I learned the value of contrarianism from Lydia Lunch. So, when I crave retreat, I remind myself to go out.

AS Can you say a bit more about why Lydia Lunch has been so significant?

KP Risk, sacrifice, generosity, articulation, humour. Food rather than deprivation. She taught us all how to eat when she spoke about the need to feed. Lydia is a curvaceous lady, not an anorexic Californian like me. I never really learnt how to take care of myself: Lydia talking about food helped a lot.

AS You were in Shadows in the City (1991) with legendary performance artist Jack Smith. How was that experience?

KP That was his last film. He was a beautiful individual, kind and gentle. I felt that, when he looked at me, he raised my consciousness. It was like having the lights turned on. He took my face in his hands and said: ‘Creature, creature, creature …’

AS Do you feel we’re living in a more permissive age now?

KP There’s a very thin veil of freedom and truth over what is currently known as democracy. I would love to invent a different vocabulary for what exists now, but I can’t articulate it today.

Kembra Pfahler’s solo exhibition ‘Rebel Without a Cock’ is on show at Emalin, London, UK until 20 July 2019.

Main image: The Voluptuous Horror of Karen Black, Capital Improvements, 2016, performance documentation. Courtesy: the artist and Emalin, London