When Sonya Rapoport Said ‘OK’ to Computers

At Berkely in the 1970s, the Spotlight-featured artist saw the growing significance of information technology

At Berkely in the 1970s, the Spotlight-featured artist saw the growing significance of information technology

In 1970, the artist Sonya Rapoport unlocked an antique architect’s desk she had purchased a decade earlier at a University of California warehouse sale. Inside, she discovered a series of geological survey maps, dating back to 1905. Filled with visual data, these sheets captured Rapoport’s imagination and she began to draw on top of them using a unique lexicon of feminist symbols – a uterus from an anatomical model, a bridge from a billiard set and an X-chromosome stencil – which she called her ‘Nu-Shu’ language: a reference to ancient phonetic script used in China’s Hunan province exclusively by women. ‘I wanted to incorporate the notions of birth and gender among the maps’ canal and drainage configurations and earth and water profiles’, she wrote in a 2006 essay in MIT Press' art, science and technology journal Leonardo , fantasizing that ‘the dams would burst open to the primordial channels latent in the superimposed imagery’.

One of the first women in America to ever receive an MA in painting (from the University of California, Berkeley in 1949), the Boston-born Rapoport spent her first decades as a painter competing in the male-dominated field of Abstract Expressionism. Following a solo exhibition at San Francisco’s Legion of Honor Museum in 1963, however, she focused her interest on experiences culled from her personal, domestic sphere. The chance discovery of the survey charts in 1970 coincided with her growing attraction to the visual language of science she encountered in the journals kept by her husband, a professor of chemistry.

This was a milestone in a singular journey from high modernist painting to conceptual and new media explorations: but then Rapoport’s life and work consistently defied stereotypes and expectations. Her subtly incisive paintings and drawings, performances and installations challenged and sometimes parodied the rigid conventions of science from a feminist perspective. But she was attracted to specialist knowledge, collaborating with scientists, anthropologists and humanities experts and eventually becoming a pioneer of art using computer technologies.

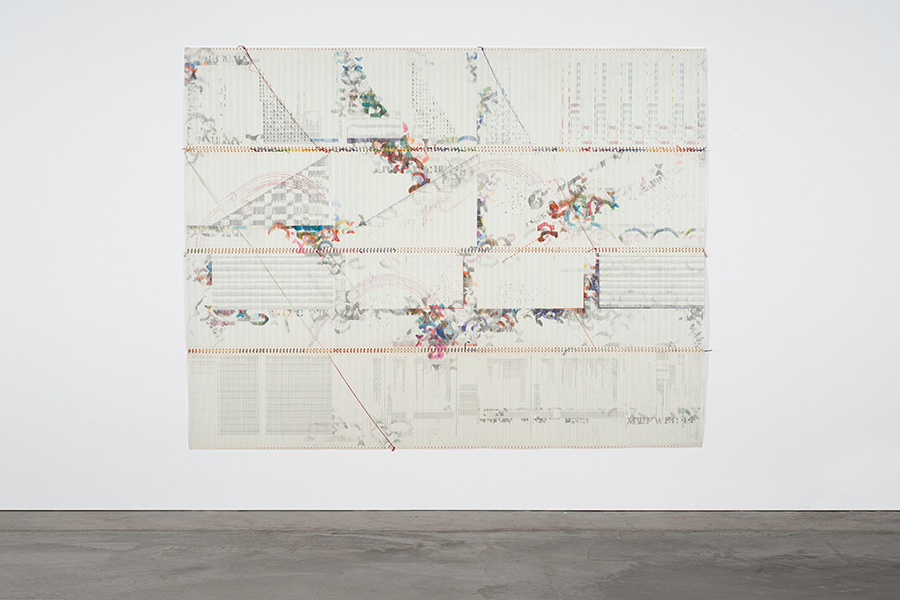

The 1970s was an especially prolific period for the artist. Six years after the discovery of the geological charts, Rapoport began experimenting with continuous-feed computer printouts, which she gleaned from the Berkeley Maths Department’s recycling bins. Rapoport was drawn to the printouts' ‘information age‘ aesthetic, a fusion of esoteric text, sprocket holes and grid lines which she would often further manipulate with graphite, colored pencil and ink stamps. For her large scale ‘Yarn Drawings’ – such as Charles Simonds (Yarn Drawing No. 16) (1976) and Untitled #10 (1976) – Rapoport stitched the printout pages together with colorful wool thread: given the gendered associations of yarn and craft more broadly, a sign of her feminist intent.

Rapoport’s interest in computers was connected to their ability to quantify qualitative information. She began to respond to the content printed on the cast-off computer paper: Jimmy Carter (1977) is a continuous feed computer printout with data on Carter’s 1976 election from Hamilton County, Ohio, which Rapoport overlaid with stencil shapes, pencil, Prismacolor, ink and solvent creating an intriguing all-over design. Using a similar approach, Rapoport created Hovenweep, the first of her ‘Anasazi’ series (1977-1986) of drawings executed on archeological research printouts, programmed by anthropologist Dorothy Washburn, who would become one of Rapoport’s primary collaborators. Washburn’s work classified the graphic rhythms of Native American pottery designs to track patterns of migration. To retrieve the printouts of Washburn’s analysis, Rapoport recounted in the 2006 Leonardo essay, she ‘happily punched data cards for computation in the CDC 6400, a room-sized computer.’ Rapoport’s graphite veneer of vivid colors and abstract shapes on this huge computer printout creates the sense of a monumental codex.

Rapoport’s work during this period ultimately led to her reinvention as a digital artist. In her later interactive installations she used computer programs to gather, process, and represent data. The Computer Says I Feel . . . (1984), exhibited this year in a solo exhibition at the San José Museum of Art, contrasted computer predictions of individuals’ emotional, physical and intellectual 'biorhythms' with their own testimonies. Rapoport's 12-phase interactive installation series Objects on my Dresser (1979-83; 2015) wedded methods of scientific visualization to personal word- and image-associations. Becoming an integral part of the community of artists experimenting with emerging computer technologies during the early 1980’s, Rapoport assumed an active leadership role in the aforementioned MIT Press journal, Leonardo. Recognition of her innovative contributions gained momentum during the last decade of her life; in an age when critical understandings of the implications of information technology are as urgent as ever, they provide prescient insight into our computer-mediated society.

Main image: Sonya Rapoport, No Rush (detail), 1973, acrylic, acrylic spray and graphite on can, 1.14 × 1.82 m. Courtesy: Casemore Kirkeby, San Francisco