Why UK Art Schools Are On Strike

The 14-day action is a response to the widespread casualization of labour, overwork and pay decreases

The 14-day action is a response to the widespread casualization of labour, overwork and pay decreases

University workers across the UK are taking part in the biggest strike action ever to hit the sector, with University and College Union (UCU) members at 74 universities striking for 14 days over the course of a month. A number of art schools throughout the country are participating, including: Courtauld Institute of Art, Glasgow School of Art, Goldsmiths, Liverpool Institute of Performing Arts, Royal College of Art, University of the Arts London (UAL), and University College London’s The Bartlett and Slade School of Fine Art.

The strike is a response to worsening working conditions in universities, including the widespread casualization of labour, unsafe workloads and, according to a 2019 study by the Universities and Colleges Employers Association, a pay decrease of 17 percent in real terms since 2009. A 2016 UCU report revealed that nearly a third of academics are working more than 50 hours per week, which is having a noticeable impact on their wellbeing. Over the past year, I have watched as several of my part-time and full-time contracted colleagues have graciously covered for absent co-workers, fallen ill as a result of overwork and, in turn, needed cover themselves, creating a vicious cycle of stress and illness.

Universities also have inexcusable equality gaps in pay and professional progression. In 2019, analysis by Times Higher Education showed that women academics typically earn 15 percent less than their male counterparts, while there is an overall pay gap of 9 percent between white and BME staff, and of 14 percent between white academic staff and black academic staff. The issues intersect and, as Dr Annie Goh, who lectures in Fine Art at Central Saint Martins, told me: ‘Casualization makes existing inequalities worse, so women and non-white colleagues are disproportionately affected. I see this in my everyday interactions at work.’

For the first time, this strike by university workers is bringing the problem of casualization to the negotiating table. According to a 2016 UCU report, around 50 percent of academic staff at UK universities are on insecure contracts – a figure that is much higher in some colleges: at the Royal College of Art, for example, 90 percent of staff are precarious workers – while a 2019 survey, also conducted by UCU, showed that 61 percent of academic staff on casualized contracts struggle to make ends meet. As an associate lecturer at Central Saint Martins, I am one of more than 2,300 casual workers at UAL. I am paid by the hour and my teaching schedule is irregular: some weeks I am paid to deliver an hour of teaching that required four hours of unpaid preparation; another week, I might work 20 hours or none at all. This inconsistency bleeds into my freelance schedule, making my cash flow erratic and affecting my ability to plan long-term. How did the situation in our art schools get so bad?

A colleague, who has taught at UAL since the 1990s, described the current pressures as ‘a perfect storm’, which has been brewing since the 2008 financial crisis. Cost-cutting measures implemented during the recession resulted in lower pay and admin being ‘pushed into the laps of academics’, raising faculty stress levels, while the art school was concurrently ‘academicized’. As my colleague pointed out, this happened during a decade in which successive, right-wing governments downgraded the status of arts and humanities education, making it even harder to access public funding for art schools.

The precarious and exploitative nature of work in universities mirrors the realities in other industries, and we are not the only sector with strikes on the horizon. Students are acutely aware of this and classroom discussions regularly turn from the burden of student debt to anxieties around post-university prospects.

Deciding to strike isn’t easy. The loss of an already-precarious income comes with another kind of loss: of the valuable contact time between teachers and students. And yet, students have been remarkably understanding and supportive of this strike. It is officially backed by the National Union of Students and, as Dr Emily LaBarge, lecturer in Writing at the Royal College of Art told me: ‘We have found a huge surge in solidarity from the Student Union post-General Election: there is a sense that people, particularly “creatives”, are trying to find ways to confront the situation we find ourselves in – to seek out alternative approaches to working, learning, politics and protest.’

Outside Central Saint Martins last Friday, a member of staff who was not striking told me he thought there was ‘a problem with the optics of the picket line. It’s too 1970s.’ While I hope that new forms of industrial action continue to evolve in response to the current slew of issues, at a time when our right to express our views in public is increasingly under threat – in October last year, the Metropolitan police banned Extinction Rebellion from protesting in London (the prohibition was later ruled unlawful by High Court judges) – showing up in person seems crucial. As LaBarge points out, strikes serve to ‘educate people on their employment rights’. They also bring together members of an atomized workforce, enabling them to share stories and find the energy to continue to do the work they love.

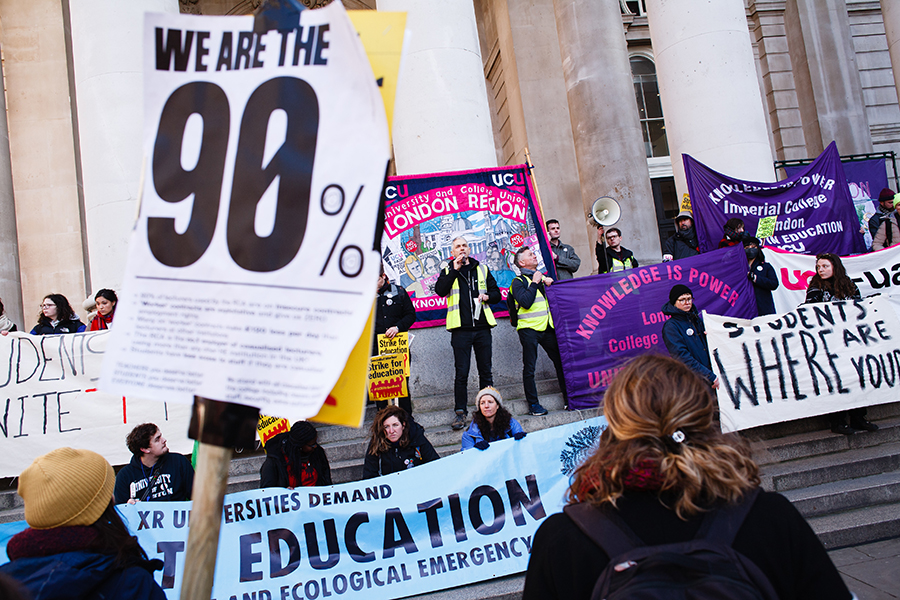

Main image: Members and supporters of University and College Union (UCU) chant slogans during the strike, 20 February 2020. Courtesy: SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images; photograph: David Cliff