The Monumental World of William Kentridge

An enthralling retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, gathers 40 years worth of works in a diverse range of mediums

An enthralling retrospective at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, gathers 40 years worth of works in a diverse range of mediums

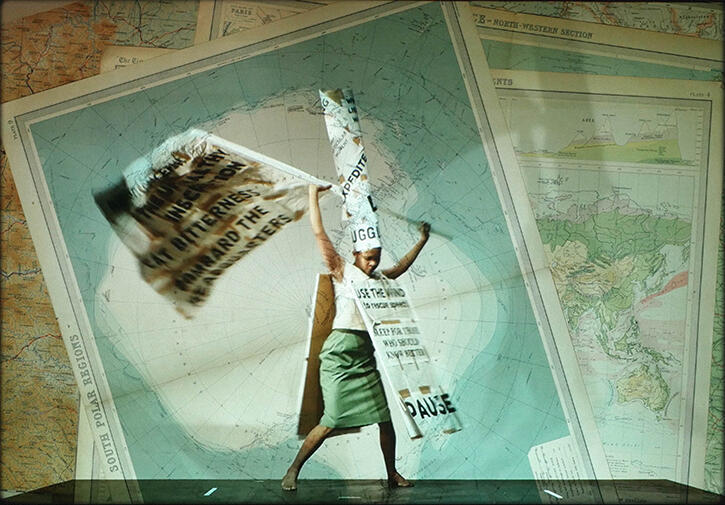

It is simultaneously simple and impossible to keep up with William Kentridge. Like the alter egos who wander through his works, he is always the same yet always moving. His characteristic gesture appears in the animated pages of De Como Não Fui Ministro d’Estado (How I Did Not Become a Monster, 2012): dressed in his regulation white shirt and dark trousers, antiquated pince-nez trailing its black cord, he paces, muses and turns, over and again, the lines of his body shifting restlessly in the trademark shimmer of his animation style. The same movement recurs constantly throughout this monumental, enthralling show, spinning out an oeuvre that is both persistently, almost doggedly, constant to itself and wildly fecund in thought and image.

To walk through the 40 years of work gathered at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) is to witness how inextricable the doggedness and fecundity are. Each powers the other in Kentridge’s characteristic technique of taking a line not for a walk but a think. The relationship is illuminated almost nowhere more clearly than in one of the smallest pieces on display: Tummelplatz (Rhino) (2016). A stereoscopic image – requiring the viewer to lean into its viewing glasses – it captures Kentridge, light in hand, drawing an instantaneous, three-dimensional rhino through the air of his studio. A literal photograph, the rhino’s wire form exists only in the moment of the movement – a gesture that gives to airy nothing a local habitation and a name.

Drawn, sculpted, animated, snipped out of film and photographic archives, the rhino form recurs so often that you feel the RA have missed a trick by not inviting child visitors to count them all. Like the other returning motifs – the tripod, the megaphone, the coffeepot, the overladen porter – creating its outline must be as instinctive a physical act for the artist as walking.

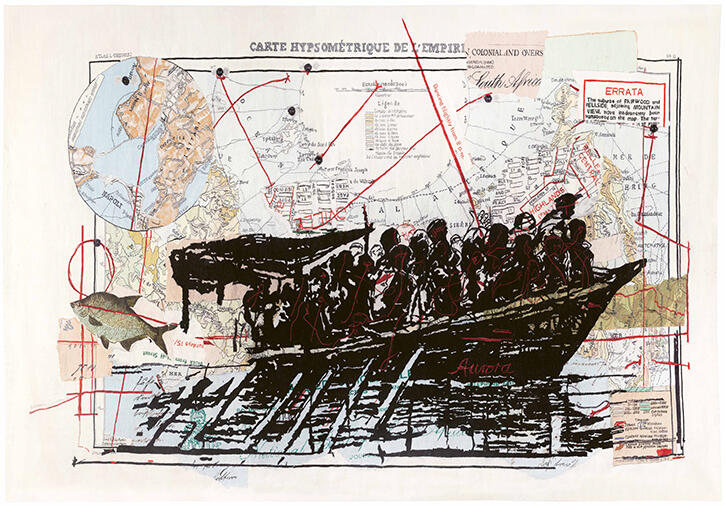

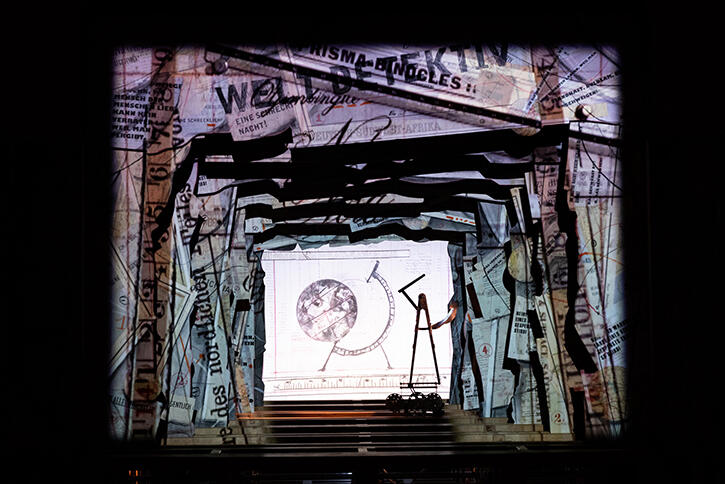

The key, though, is the way that Kentridge’s motifs accrete meaning as they replicate – a process that, despite the major shows and commissions he has had over the last decade or so, has never been so visible as it is here. Along with curator Adrian Locke, the artist has transformed the RA galleries into a kind of Kentridge World, complete with wall drawings and props, throughout which echoes the soundtrack by long-term collaborator, composer Philip Miller. Moving from his Max Beckmann-like drawings of the 1980s through his series ‘Drawings for Projection’ (1989–2003) and onward, the familiar outlines grow into a kind of ideogrammatic script. Eventually, they appear as a language with its own flexible syntax and grammar, tailormade for the expression of Kentridge’s concerns. In animations and flipbooks, they shift one into the other, metamorphosing with fluent significance in an unbroken weave.

The rhino is symptomatic of how that language works. A symbol of Kentridge’s native continent, it’s also a document of the European art history that inflects his work and the European colonialism that scars his South African homeland. Albrecht Dürer’s encyclopaedic pencil hangs over Kentridge’s drawing practice. The exploitation returns in the white hunters seen killing a real rhinoceros – unarmoured, harmless, grazing – at close range in archive film projected onto the mechanical theatre of Black Box / Chambre Noire (2005). But then there is humour, too: the clowning theatre of the absurd, funnelled in through Eugène Ionesco’s Rhinoceros (1959) and Kentridge’s time spent training at Paris’s Ecole Jacques Lecoq. In a classic Kentridge stroke of serio-comic absurdism, Black Box later sees the trophy resurrected as a cavorting silhouette that dances, prances and somersaults over a megaphone bearing the legend ‘TRAUERARBEIT’ (the work of mourning).

The net result is a triumphant retrospective that will have viewers’ heads spinning with delight and puzzlement. In case anyone still had their doubts, it is impossible to leave thinking that Kentridge is anything less than one of the greatest artists of his generation.

‘William Kentridge’ is on view at Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 11 December.

Main image: William Kentridge, The Conservationists' Ball (detail), 1985, exhibition view, 2022, charcoal, coloured pastel and gouache on paper (triptych), 198.5 × 97.5 cm (left), 198.5 × 138.5 cm (centre), 198.5 × 97.5 cm (right). Courtesy: © William Kentridge and Rupert Museum, Stellenbosch