Written on Water

The highs and lows of the 53rd Venice Biennale, ‘Fare Mondi Making Worlds’

The highs and lows of the 53rd Venice Biennale, ‘Fare Mondi Making Worlds’

Jennifer Higgie

Not long after visiting the 53rd Venice Biennale, I travelled to Athens. The new, astonishing, Acropolis Museum, designed by Bernard Tschumi, had just opened, and I spent a few hours there, wandering among the 4,000 antiquities, which are exhibited over an area of 14,000 square metres. Attempting to understand the Parthenon’s breathtakingly complicated history through these fragments – a horse’s head here, an athlete’s or god’s limb or enigmatic figure there – and subsequently reading Mary Beard’s fascinating history of the site (The Parthenon, 2002), in which she discusses the impossibility of consensus about the meaning of these objects and their wider cultural and symbolic functions, something began to nag at me. And then I realized what it was: despite the age difference of the things I was looking at, my visit to the Acropolis museum reminded me of my visit to the Venice Biennale. In both locations, visitors are required to grapple with a staggering amount of objects and information, much of it fragmented, while simultaneously wrestling with the facts and fallacies of history and memory. It’s not surprising that it dawns on most visitors to both cities that they know, at best, very little about the original motivations for the existence of these buildings and objects or the lives of the people who made them – to do so would require years of dedicated study. None of which, I hasten to add, means to imply that visits to both cities aren’t worthwhile – of course they are. But it’s complicated.

Despite some positive changes, the 53rd Venice Biennale, directed this year by Daniel Birnbaum (who, it must be stressed, has nothing to do with the national pavilions), isn’t radically different from previous incarnations. The show’s title, ‘Fare Mondi Making Worlds’, is neat, diplomatic and vague. The Arsenale is thankfully less filled with work than in previous years (Birnbaum included 90 artists – of whom roughly 40 are women – in the shows he curated over two locations), is broadly international and cross-generational and the addition of a new sculpture garden is welcome. As in previous years, however, the size of the show is still overwhelming, and, without a really clear curatorial premise, confusing to navigate with any real sense of direction other than personal taste.

The Palazzo delle Esposizione (newly created in the venue formerly known as the Italian Pavilion) also includes some great work from artists from different countries and generations that is elegantly and, on the whole, cleverly installed; however, its overarching curatorial aim, ‘to emphasize the process of creation’, is, again, simply too general to engender much tension, discussion or argument – although Birnbaum certainly does, as he aims to, ‘highlight the fundamental importance of certain key artists for the creativity of successive generations’.

The main exhibition is now flanked by literally hundreds of works by artists from 77 countries and supported by 44 collateral events and exhibitions. This enormous range of work is, in turn, predictable, lacklustre, engaging, bombastic, bewildering or simply dull. Overall, the mood is melancholic and self-reflective: a surprising amount of work employs Venice as its subject and focus, and, to a lesser extent, is concerned with the politics, the problems of translation (from language-to-language, culture-to-culture) and the environment. Women artists are more absent than usual, Africa is, once again, virtually unrepresented, and the more corrupt and right-wing aspects of Italian politics are made glaringly evident in the scandalous Italian Pavilion (see Barbara Casavecchia’s report below). Off-piste national exhibitions (only 29 pavilions are in the Giardini) are, as usual, difficult and time-consuming to find and, unsurprisingly, once again, the two Golden Lion jury prizes went to men from powerful Western countries.

Generally speaking, it is increasingly evident that super-shows such as the Venice Biennale need some kind of radical overhaul. The sheer visual cacophony of seeing so much art in a short space of time (most visitors I spoke to were in Venice for about three days) can flatten difference, suck enthusiasm from the viewer and drown out work that is nuanced, quiet or difficult. Time, geography and history feel like they’re in freefall during the Biennale; anachronisms rub up against invention – at moments, it’s like witnessing an astronaut attempting to reach the moon in a horse and carriage. I have now been to six Biennales, and each time the majority of visitors I have spoken to express a mix of guilt about not seeing everything and not understanding or liking much of what they have seen – judgements tempered by exhaustion, cultural confusion and ignorance usually expressed along the lines of ‘I have no idea what is going on in Azerbaijan. How am I meant to react to its show?’ Which is, of course, supposedly one of the assumed aims of the Biennale: it’s meant to foster international understanding and, on some levels, it possibly does, but these things are hard to quantify.

Time, geography and history feel like they're in freefall during the Biennale.

As Birnbaum wisely points out in his catalogue essay: ‘If one maintains that a cultural event with participants from many cultures is to be more than a stage where one culture is put on display to another, then it may be important to insist on the complexity of individuals, not to mention the communities they form’. However, without a consensus about how pavilions are commissioned (which would, I hasten to add, given the logistics, be almost impossible to change), not only can repressive governments control and censor their own representation (ironically this year, the case with Italy), but the mediocre often win out over the exemplary (conservative juries will, of course, choose conservative artists to represent them). While national pavilions continue to be pitted against each other in the prize-giving (and it’s naive to suggest otherwise), age-old hierarchies of value based on culturally specific notions of taste will be reinforced – however worthy the recipients, it’s a system that perpetuates antiquated notions of nationalism and, in some respects, colonialism. (Initiated in 1938, the Grand Prizes were abandoned in 1968; they were reinstated in 1974 as ‘Golden Lions’.) Thus, at the heart of this unwieldy and often – despite the chaos and exhaustion – joyful beast that is the Biennale lurks a curious contradiction: it’s a show about celebrating creativity that seems resistant to change and, despite its apparent celebration of difference, is often mired in the worst kind of politics. For the institutions of contemporary art to continue to embrace such a model makes less and less sense. Birnbaum wrote in his catalogue essay: ‘Perhaps art can be one way out of a world ruled by leveling impulses and dull sameness. Can each artwork be a principle of hope and an intriguing plan for escape?’ This is a fine sentiment, but one impossible to put into place without the support of the new structures needed to house it.

Dan Fox

It’s easy to knock the Venice Biennale; to forget the effort put into making it happen and overlook what it means to have somewhere to come and see what artists are doing across the world; to sound spoiled and forget that, were art like most other industries, the Biennale would be held in a grim convention centre and not a beautiful, sinking city under the Adriatic sun. Venice, surely, must mean something to the multitudes of artists, critics, curators, dealers, students, collectors and tourists who go there every two years?

Venice is a cultural festival like any other but the art edition of the Biennale just happens to be where you go to see Joan Jonas rather than Neil Young. But La Biennale is a grand old matriarch that considers itself a cut above the festival rabble. Its official international exhibition is invariably given some faux-profound, catch-all theme; Harald Szeeman’s 2001 ‘Plateau of Humankind’, for instance, or this year, Daniel Birnbaum’s ‘Fare Mondi Making Worlds’, as if to suggest that this is it: art’s definitive statement on the human condition. It’s where artists are sent by state organizations to represent their countries in a park full of architectural fantasias, or in exquisitely shabby baroque palazzi, rented at an extortionate rate from brokers turning a profit on international cultural prestige. It is where wealthy collectors such as François Pinault come to establish art-filled monuments to themselves; transforming huge Venetian properties into exhibition spaces that look like expensive loft conversions – exposed brick, brushed steel and spectacle. The problem with Venice – both Biennale and heritage city – is that it means too much.

The sheer number of official and unofficial exhibitions makes reports on Venice sound like the Saturday football results.

But there I go, knocking Venice and neglecting the duty of critical reportage. I should tell you how much I liked Lygia Pape’s Livro da Criacao (Book of Creation, 1959–60) in ‘Fare Mondi’; paper sculptures depicting civilization’s technological evolution, and the juxtaposition of these with Philippe Parreno’s time-lapse film of blooming flowers, El sueño de una casa (The Dream of a House, 2001). Or Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s film De Novo (2009) about an artist who makes five attempts to show at the Biennale. Or Pae White’s bearded birdsong callers, who wandered amongst her installation of chandeliers made from birdseed, Weaving, Unsung (2009). I could write about how Birnbaum’s show was, on the whole, lacking in surprises, but that his creation of a sculpture garden and Biennale archive were positive developments. I might question why Tobias Rehberger was awarded a Golden Lion for his Biennale cafeteria; to me his design looked purely cosmetic, and instantly dated.

Maybe I should describe how rewarding it was to discover, hidden down labyrinthine alleyways, the hypnotic, pataphysical films by João Maria Gusmão and Pedro Paiva at the Portuguese Pavilion; or the small show of late work by James Lee Byars in an off-site Palazzo. Or how Tirdad Zolghadr’s United Arab Emirates pavilion, with its architectural models of cultural theme parks in UAE, was upfront about the politics of national representation in Venice. I could argue that Shaun Gladwell’s collision of Mad Max with Renaissance pieta at the Australian Pavilion was excruciatingly corny, or perhaps draw you a picture of my jaw dropping in Claude Lévêque’s macho, vainglorious French Pavilion (think May ’68-themed sex club, with wind machines).

I could ask whether the opinions Liam Gillick’s ‘talking cat’ had about the collapse of neo-liberalism were drowned out by all the fuss over British artist Gillick exhibiting a ‘talking cat’ in the German Pavilion. I might opine that in the British Pavilion, Steve McQueen’s new film, Giardini (2009), was technically exquisite but hobbled by coy narratives and allusions to Andrei Tarkovsky’s 1979 film Stalker.

I could observe how this, and many other works at the Biennale, were ‘about’ showing work in Venice, or Venice itself, and how this surfeit of self-reflexivity seemed less about the will to render power structures transparent, and more about tedious nods and winks. Or we could just enjoy how Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset, in a witty camp détournement, transformed the Danish and Nordic Pavilions into wealthy art collectors’ bachelor pads.

There is a disconnect between expectation and sheer number of official and unofficial exhibitions which makes reports on Venice sound like the Saturday football results; litanies of who performed well, and who didn’t. Maybe it’s time to follow the lead of Roman Ondák’s Loop. Ondák brought the bushes and trees surrounding the Czech Republic and Slovak Republic pavilion into the exhibition room itself, erasing the threshold between garden and art space. Perhaps the next Venice Biennale should be postponed; leave it to run wild for a few years, let new plants to take seed, overgrowing crumbling old structures.

Barbara Casavecchia

The new Italian Culture Minister's biography is titled Me, Berlusconi, Women and Poetry.

The Padiglione Italia – which at this year’s Venice Biennale hosts an archaic ‘Omaggio a Pietro Cascella’ (Homage to Pietro Cascella) as a tribute to the late sculptor, and the muddled group show ‘Collaudi (Omaggio a F.T. Marinetti)’ (Tests: Homage to F.T. Marinetti) – has only been in existence for two Biennales. After decades of angry complaints and petitions about the fact that the permanent ‘Italian Pavilion’ building in the Giardini has traditionally been the site of an international group show, in 2007 the Culture Minister Francesco Rutelli opened an 800-metre-square, all-Italian pavilion at the Tese delle Vergini in the Arsenale, and nominated Ida Gianelli, then director of the Castello di Rivoli, as its first curator. Gianelli chose Arte Povera artist Giuseppe Penone and glamorous art star Francesco Vezzoli, whose video Democrazy (2007) focused on television propaganda strategies. How appropriate.

Elections came, bringing with them a new minister, Sandro Bondi, whose biography was published in 2008 under the title Io, Berlusconi, le Donne, la Poesia (Me, Berlusconi, Women and Poetry). Don’t laugh, grazie. Whilst communist mayor of Fivizzano in Tuscany, Bondi had become friends with the sculptor (and fellow former communist) Cascella, who lived in the area. In the early 1990s, shortly before Silvio Berlusconi entered Italian politics and became Prime Minister, Cascella was sculpting his marble mausoleum, and introduced Bondi to him. Bondi soon became the Cavaliere’s secretary, collaborator and faithful advisor, and later party coordinator, while publicly proclaiming his devotion on television debates and in poems, such as the disarming ‘A Silvio’ (To Silvio – a hit among Italian bloggers). Last autumn he nominated Mario Resca, ex-chairman of McDonald’s Italy, as the ‘supermanager’ of all museums and archaeological sites, causing uproar among the intelligentsia.

Things had just settled down when Bondi announced that the Padiglione Italia had doubled its exhibition spaces and its curators: Luca Beatrice and Beatrice Buscaroli were the newly appointed curators, quickly nicknamed ‘B&B’. Writing in the Italian broadsheet Il Corriere della Sera, journalist Paolo Conti introduced us to their CVs: ‘Beatrice writes for [the weekly paper] Il Domenicale published by Marcello Dell’Utri [Senator and senior advisor to Berlusconi] and for Libero [a right-wing newspaper], and teaches at the Brera Academy of Art. Buscaroli writes for Il Giornale [owned by Berlusconi’s brother Paolo] and Il Domenicale, and teaches history of art at the University of Ravenna–Bologna. […] In short, the political Centre-Right recaptures a crucial area of Italian culture.’ The fanfare ‘the cultural hegemony of the Left is over’ was played on, thus putting a political spin on the event, and confirming how – to paraphrase curator Francesco Bonami’s statement in the catalogue essay to his exhibition ‘Italics’ (Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 2008) – that in Italy affiliations count more than individuals and contents. Much ado about little.

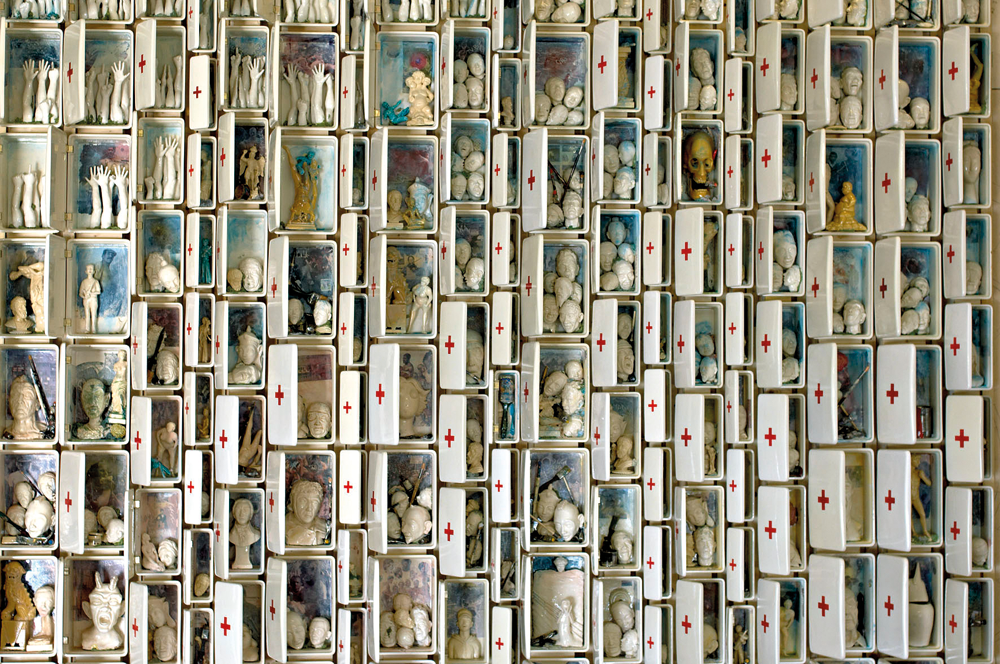

In a country afflicted by gerontocracy and decadence, ‘Collaudi’, with its 21 participants, looks like a feeble attempt to kill some of the father figures from the 1960s and ’70s, only to establish a new parental landmark, starting with Transavanguardia and the resurrection of painting in 1979, here represented by Sandro Chia. Notably, the pavilion displays only tiny quantities of the compulsory optimism of the Berlusconi era. More than passatista (passé), it could be labelled as fairly pessimista (pessimist), thanks to works such as Bertozzi & Casoni’s ceramic, trompe-l’oeil fallen Christmas tree (Rebus, 2009) and 600 first aid kits (Composizione non finita-infinita, Composition Unfinished-Infinite, 2009), the surreal paintings of Marco Cingolani (Election Day, 2009), or a video like Untitled (The Party is Over) (2009) by Elisa Sighicelli, with its imploding fireworks (Sighicelli and performance artist/sculptor Sissi are the only two women in the show).

A modest proposal for the next celebratory round of the Padiglione Italia: a homage to Fabio Mauri, who died in May. In 1971 he staged a great action/performance titled Che cosa è il fascismo? (What is Fascism?) in Rome; in 1980 he organized and directed the memorable Gran Serata Futurista (An Evening of Futurism) in L’Aquila. OK, so maybe it would be a return to 1970s again, but it might at least be something worth returning to.