The Year in Sounds and Stories

Artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan on the pivotal sounds and stories from 2017, from historical fiction to Vince Staples’s representation of race

Artist Lawrence Abu Hamdan on the pivotal sounds and stories from 2017, from historical fiction to Vince Staples’s representation of race

One of the highlights of the year for me was catching rapper Vince Staples on his European tour to promote his second full length album Big Fish Theory (2017), at Berlin’s C-Club. In comparison to his previous album, the tracks of Big Fish Theory are more calibrated for the live act, excellently mastered to cut through any sound system and crowd size. Staples was alone on stage, lit from the back by powerful spots so no matter how vigorous his dancing, jumping, striding was, his face never touched the light. It was single performer, human shadow puppetry; he only appeared to us as a negative shape obstructing the colourful stage lights and smoke behind him.

For me the scenography of the gig developed out of the frustration of his relation to the crowd on his last European tour, as evidenced by his bars on ‘Lift Me Up’ (2015): ‘Was standin’ on this mezzanine in Paris, France. Finna spaz cause most my homies never finna get this chance. All these white folks chanting when I asked ‘em where my ni**as at?” Goin’ crazy, got me goin’ crazy, I can't get wit' that’. This time he wanted to share that frustration with the crowd itself, hammering home both lyrically and visually a message for all those ‘I don’t see race’ fools – for in the absence of light, we were forced to perceive blackness. If you have seen Kerry James Marshall’s self portrait Black Artist (studio view) (2002), then you can imagine the potency of this performance of one’s self image. Marshall’s portrait happened to be another standout work I encountered in 2017 at the MCA in Chicago exhibition of their collection curated by Omar Kholeif.

One week in August, as I walked back and forth to my studio in Berlin, I listened to Hilary Mantel’s 2017 BBC Reith lectures. I have never read her books but these lectures are themselves a work of literature, especially ‘Silence Grips the Town’. This piece of historical fiction tells of how an obsessive relationship with history killed the young Polish writer Stanisława Przybyszewska. These lectures are, then, a meta-historical fiction, having as much to do with their subjects as about the role of historical fiction as a political and aesthetic project. It was inspiring for me to hear astute observations about history as craft. For me, as a purveyor of artifice that touches and tries to speak to the real world, it is a lesson in the ways in which extremely imaginative and creative work can emerge from hard empirics, attention to minute details and – dare I say it – fact.

In February Maha Maamoun’s show ‘The Law of Existence’ was exhibited in the twin ground-floor galleries of Beirut’s Sursock museum. Going right, you were met by a dark room lit only by a suspended projection screen that was covered in a specific material that allowed it to glow and bleed light into the room. What’s more, this half-screen, half-floating object was an unusual shape calibrated in size for a rare aspect ratio specific to the mobile phones that had filmed – under limited, improvised sources of light – the raiding of files and drawers in the State Security buildings in Cairo during the 2011 revolution. This was the simple, incandescent installation of her work Night Visitor: The Night of Counting the Years (2011). In the next room was Dear Animal (2016), my favourite of Maamoun’s films to date. The work addresses the toxicity of political and public talk in relation to the latest chapter in the Egyptian revolution. Dear Animal uses the cinematic device of the animal as a political frontier at which issues of subjecthood and citizenship can be defined and discussed anew.

At the tail end of 2016, and with its reverberations lasting long into 2017, was a reading by the novelist Tom McCarthy in discussion with Eyal Weizman, which was the closing event of an excellent conference organized by Ines Weizman at the Bauhaus University in Weimar. The novelist embodied in his own voice the encyclopedic, hysteric and paranoid world of his protagonists and this was punctuated by inspiring interludes of discussion with Eyal in which they both articulated the converging and diverging ways in which they, respectively through their practices, measure and map cracks, gaps, holes, blurred pixels and the omissions in human memory.

Also in 2017, Natasha Ginwala gave us her expertly curated Contour Biennial in Mechelen, Belgium. What impacted me the most was the bringing together of the 1961 short film by Rene Vautier J’ai huit ans and the video and multimedia installation The Stealing C*nt$ (2017) by Karrabing film collective. Although both works were made in different times, places and languages (both artistic and verbal), together they stood as an argument for the lasting role of the artist as auditor and producer of testimony to violent events. It shows that if we only ever left this labour to those working in human rights and advocacy then we would operate solely within the confines and limits for speaking what is sometimes unspeakable. These effects are measurable only by non-legal practices of listening and documenting. Artists not only source testimony but also experiment with the nature of testimony itself, its conditions and what constitutes it.

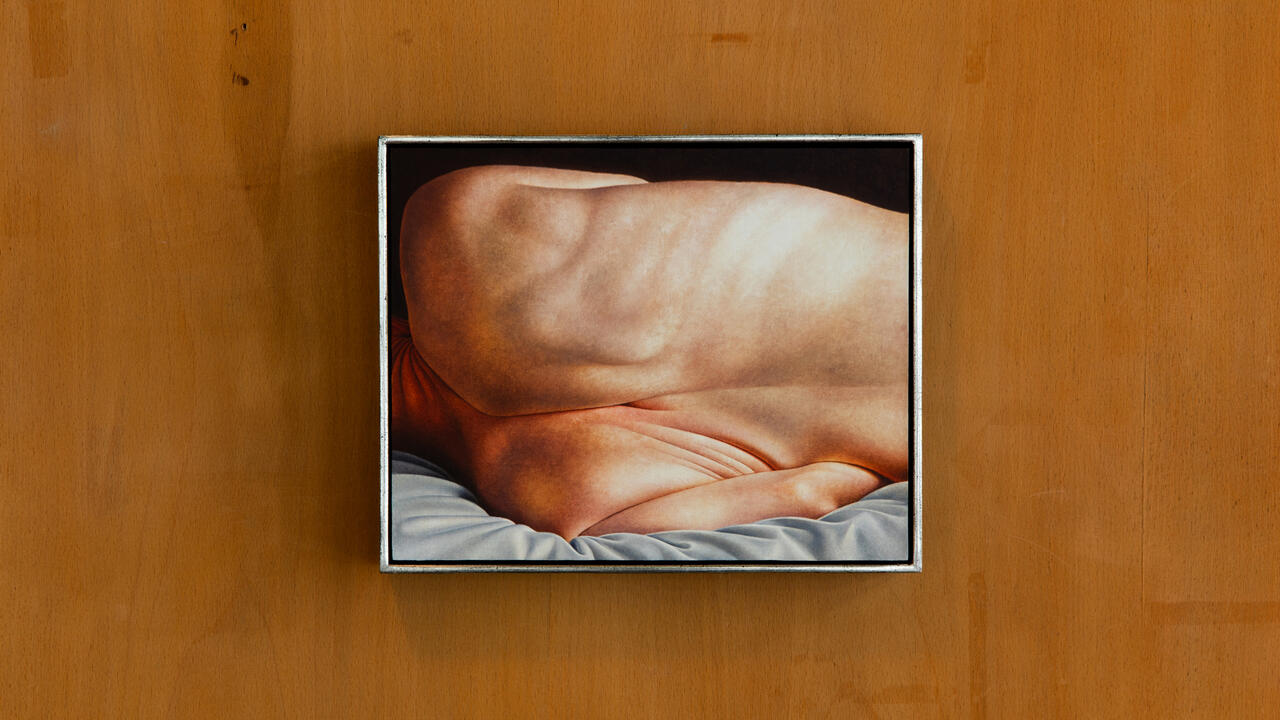

Other excellent art work encounters this year included George Awde’s Public Shadows (2017) installation as part of Ashkan Sepahvand’s curated exhibition 'Odarodle' at the Schwules Museum in Berlin, that ran from July to October, and Wolfgang Tillmans’s Truth Study Centre which was for me the strongest part of all the intermingled bodies – both machinic and human – that populate the world he created for his retrospective at the Tate Modern, London, in spring.

Wolfgang Tillmans, truth study center, 2017, installation view. Courtesy: the artist and Tate Modern, London