Adji Dieye Unveils the Role of Language in Post-Colonial Senegal

At Fotomuseum Winterthur, ‘Aphasia’ addresses the barriers that the dominance of the French language imposes on civic participation

At Fotomuseum Winterthur, ‘Aphasia’ addresses the barriers that the dominance of the French language imposes on civic participation

Language is often said to be the key to the world, but it is also a colonial project that sought to reflect the dominance of the colonisers’ culture and ideology in large parts of the globe. This aspect of language is the focus of ‘Aphasia’, Italian-Senegalese artist Adji Dieye’s solo exhibition at Fotomuseum Winterthur, which takes its name from a medical disorder that leaves a person unable to communicate effectively with others. Featuring an eponymous two-channel film shot in 2022 in Dakar, where the artist is partly based, the exhibition uses this condition as a metaphor to explore how linguistic hegemony influences a nation’s ability to build a post-colonial identity.

Entering a darkened room through a pair of heavy curtains, viewers are greeted by a projection of Dieye haltingly reading excerpts from the speeches of various Senegalese presidents, which have been delivered annually on 4 April, Senegal’s Independence Day, since the country became a republic in 1960. Written in French, Senegal’s official language, these speeches are ostensibly a way for the country’s elected leaders to address their citizens. Yet, despite almost all official life, education and politics of the country being conducted in French, the vast majority do not speak it fluently, effectively creating a barrier to civic participation. Over the course of the performance, Dieye’s speech shifts to a polyphony, as she assembles the voices of friends from Senegal and its diaspora into a chorus that struggles to verbalize these significant addresses.

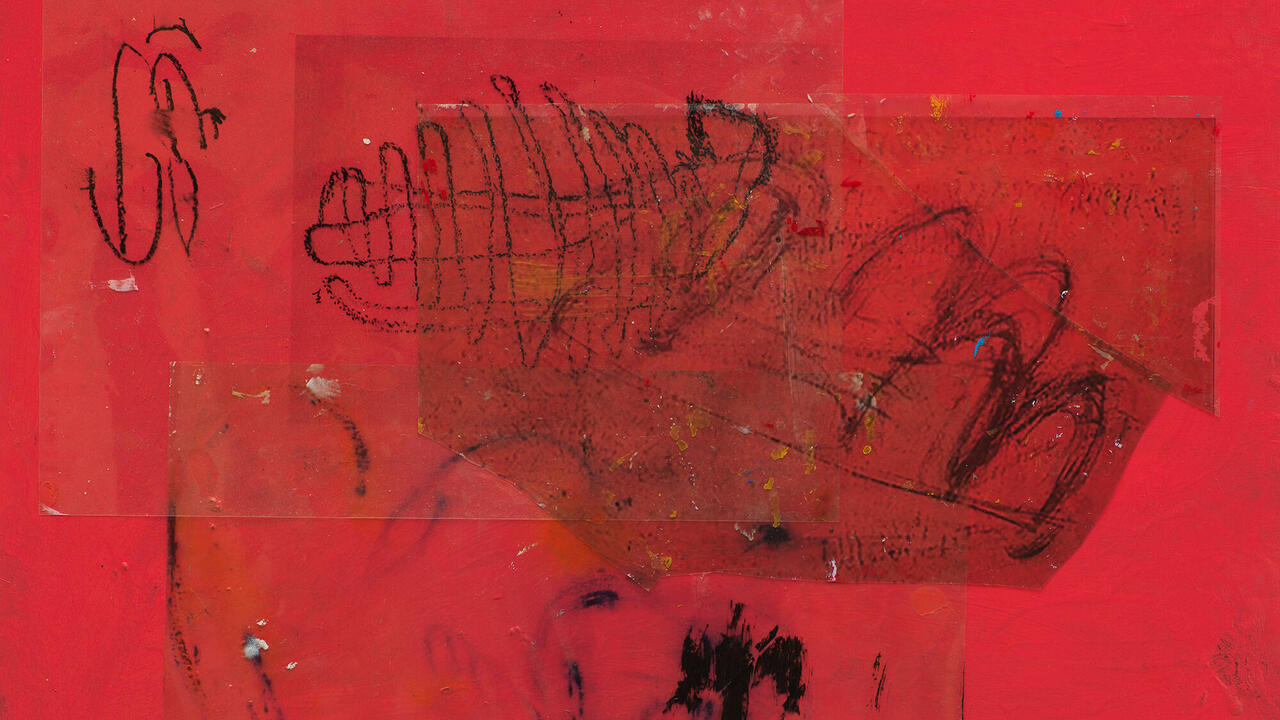

Collected from the country’s National Archive, the chosen passages convey the patriotic ideology of a newly born state but, in the face of unfulfilled promises, this hope is long gone. Even the locations in the video seem to reflect this shattered dream. Vacant apartment buildings, stone wastelands, deserted public spaces – all captured with a skilful eye. The only person in this metropolitan scene is the artist, in a loose-fitting red suit, her face obscured by the pages of the manuscript she holds in her hand. You hear the French passages but, if you don’t know the language – if you lack this key – this world remains closed to you. The scenes of Dakar’s faded architectural splendour only intensify the feeling of being left out of this promise of a better future.

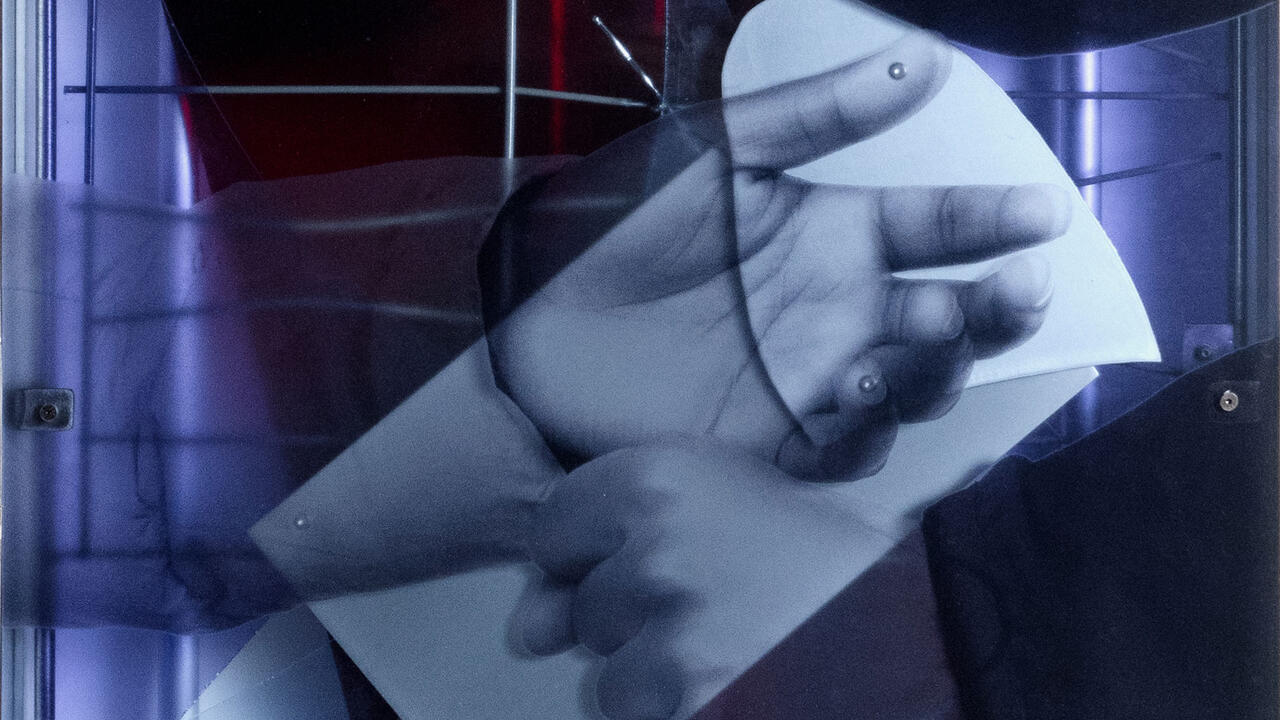

On the other side of the room, divided by translucent fabric, a second projection shows images of a woman wrapped in a patterned scarf as she sits in a bedroom, a man singing confidently in a hallway and a group chanting in front of a mosque. Each character communicates in Wolof, the most widely spoken of Senegal’s many languages. Yet, despite the headphones viewers use to listen to the audio, the French passages from the first projection bleed into the intimate space of the second, underlining how much the public sphere intrudes into the private. As in the first video, viewers are denied the guidance of subtitles but, by failing to understand what is being said, different elements of the video come to the fore, from the gently swaying gestures of the woman in the bedroom to the curious children drawn to the man’s singing.

The woman is Dieye’s aunt, reciting the artist’s genealogy across four generations. As she speaks, the contrast to the sterile scenes from the urban space is striking. ‘Aphasia’ presents two kinds of archives – written and oral, thus static and living – displaying two very different forms of knowledge. But which is the more credible narrative of history? Dieye brings both versions to life, leaving it up to the visitor which one they choose to believe.

Adji Dieye’s ‘Aphasia’ is on view at Fotomuseum Winterthur until 29 May.

Main image: Adji Dieye, Aphasia, 2022, film still. Courtesy: the artist