Michael Clark: The Artists’ Dancer

From enfant terrible of British ballet to a retrospective at the Barbican Gallery, how the choreographer and performer found a home in the contemporary art world

From enfant terrible of British ballet to a retrospective at the Barbican Gallery, how the choreographer and performer found a home in the contemporary art world

In May 1980, on the beach at Pett Level, East Sussex, David Bowie shot the outdoor scenes of the video for his new single ‘Ashes to Ashes’, to be released in August. The song famously reanimates Major Tom, the stranded astronaut from Bowie’s first hit, ‘Space Oddity’ (1969). The video is more obscurely retrospective: the singer’s complicated Pierrot costume refers to his role in choreographer Lindsay Kemp’s Pierrot in Turquoise (1967) and to a painting on the sleeve of Bowie’s second self-titled album from 1969. In the weeks before filming, Bowie had recruited an exotic, younger entourage from Blitz, the London nightclub that birthed the new romantics. Dressed in nunnish black, they flank the delicate clown on the shore and, as they process towards the camera, two of them execute an enigmatic gesture: raising one arm straight and then stooping to bring it palm-down onto the shingle – helping Bowie to bury his creative past.

Eighteen years later, in the first minutes of Sophie Fiennes’s documentary The Late Michael Clark (2000), we find the dancer and choreographer filmed in Super 8 on a Scottish beach. It is 1998, and Clark has been out of the public eye for four years, having abandoned an incomplete Royal Ballet project at the height of his fame – and his drug addiction. He has been living with his mother, Bessie, near Fraserburgh on the northeast coast, but is ready to work again. He has numerous answerphone messages, which play over the film’s opening scenes: the newspapers want to know about his lost years. More importantly, his reconvened dance company is about to perform, at the Roundhouse in London, a work called current/SEE. In the meantime, here is Clark on the beach with Bessie, walking towards the camera and enacting three perfect iterations of the ‘Ashes to Ashes’ gesture – followed, so very briefly, by a little precious Pierrot waddle.

It’s no surprise that Clark should have had a casual Bowie reference at his fingertips. Since The Late Michael Clark was filmed, several of the choreographer’s works have featured the music of Bowie and his peers, pre- or postpunk. To a simple, rock ’n’ roll . . . song. (2016), performed at the Barbican – where he is due to be the subject of a major exhibition, opening on 7 October 2020 – included the music of Erik Satie, Patti Smith and, in its third act, Bowie, who had died at the start of that year. ‘Aladdin Sane’ (1973) leads into songs from the album Blackstar (2016), released just two days before Bowie died. For an artist of Clark’s age, who traces his creative and sexual awakening to seeing the musician perform as Ziggy Stardust on television in 1972, you might reasonably conclude that his Bowie connoisseurship, his knowledge of a decades-old gestural repertoire, is purely a matter of nostalgia.

But what if Clark’s on-camera citation of ‘Ashes to Ashes’ is actually evidence of something else? A degree of care, noticing and precision that’s entirely of a piece with his balletic classicism, his career-long quotation of the canon of traditional movement. Since Clark was a young dancer in the late 1970s, critics have spoken about the clarity and exactitude with which (now solely as a choreographer) he invokes ballet. In the same breath, he’s been celebrated, condemned and condescended to for adding so many extra-balletic elements: from pop music, fashion and club hedonism to contemporary art and gay culture. As if all of these references were merely drawn from anarchic stuff he’d found lying about in plain sight. As if there were no taste involved – as much choice, affinity and commitment in quoting a move from an old Bowie video as in inventing a new dance vocabulary for Igor Stravinsky.

It is possible I might not have noticed such details, nor have paid such rapt attention to Clark as he quotes Bowie on screen, if the dancer himself had not proved so elusive at the time of writing this piece. Of course, interviews in person with Clark and his associates have been impossible during the COVID-19 lockdown – but the truth is he is, at present, less available and perhaps less trusting of those who come to tell his righted-Icarus tale again. In the past, Clark has been unguarded about the highs and lows of his life and career; it would not be unusual, in an artist about whom the word ‘fragile’ has often been used, to shrink from the media round. So, for now, no phone calls, no emails, no face to face – he would not recall the one time, years ago, that we shook hands – but, instead, as much as I can gather from remembered performances, the visual archive, old interviews.

and photograph: © Alexander James

Clark was born in 1962 in rural Aberdeenshire. When he was four years old, he begged to be allowed to join his sister at lessons in Scottish dancing. From 1975 to 1979, he attended the Royal Ballet School in London, where he was quite the golden boy. It was the era of teenage glue-sniffing and the punkish Clark later liked to tell how glue had been discovered in his locker, but he could not be expelled because he was the lead dancer in the end-of-term production. In other words, he established early on, as myth and reality, the combination of classicism and anarchy that made his name during the following decade. Which also means, looking at his early career, that it’s too easy to forget the experimental space in between. The teenage Clark may have been admired by such venerable figures in British dance as Frederick Ashton and Ninette de Valois, but he also attended a summer school in New York with the Merce Cunningham Dance Company, met John Cage, worked with Karole Armitage and was well acquainted with the history of avant-garde practice in the US, particularly the Judson Dance Theater and postmodern choreographers such as Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown.

At the end of his training, the Royal Ballet offered Clark a place in the company, but he turned it down and joined instead the Ballet Rambert, which had concentrated on contemporary dance since the 1960s. A stint as choreographer-in-residence at the Riverside Studios arts centre followed in 1980, which allowed him to begin developing his own vocabulary, juxtaposing balletic grace with a range of physical wit and deliberate awkwardness – a hopping, dragging, limping style. Footage of Clark and his company in the early 1980s reveals that many of his signature movements were already in place. There is his notable épaulement, or rotation of the back and shoulders. The body frequently stays rigid and upright while one foot, in a rond de jambe, describes on the plane of the stage the circular limit of its reach. Combine the rigour of such movements with an array of everyday gestures and you have a dance that the writer Michael Bracewell described in Michael Clark (2011) as ‘at once violent, ethereal, detached and intent’.

Of course, it was not only his formal dazzle that made Clark famous in the 1980s: there was also the fact of his marrying a classically inflected version of contemporary dance to what seemed to some like outré material and aesthetics. Eventually, Clark would incorporate into the work his critics’ aghast reactions; in his 1985 production our caca phoney H. our caca phoney H., a cast member was tasked with shouting: ‘Michael, when are you going to cut out the gimmicks and just dance?’ He formed Michael Clark and Dancers in 1984 and, in the same year, began collaborating with The Fall, whose slurred vocals and repetitive drive allowed him sufficient space and ambiguity in which to work. (‘I think of my company as a band, with me as the front person,’ Clark told The Sunday Times in 1984.) His first production with The Fall, at the Riverside in 1986, was Hey! Luciani: The Life and Codex of Albino Luciani: a play by the band’s frontman, Mark E. Smith, about the death of Pope John Paul I in 1978. Later in the decade, Clark and the band would collaborate on I Am Curious, Orange (1988): improbably, a ballet about the ascent of William of Orange to the British throne in 1689. But one of the sharpest relics of Clark’s association with The Fall is a television performance from November 1984. On the BBC’s rather worthy music show ‘Whistle Test’ (1983–88), Clark and three other dancers spent five minutes as violent marionettes in assless costumes while the band (mostly in darkness) played their relentless track ‘Lay of the Land’.

The costumes for that performance were designed by Stevie Stewart and David Holah, of fashion label BodyMap, and the headgear by Leigh Bowery. If there is one aspect of Clark’s work in this period that conventional dance critics could not countenance, it was Bowery’s presence in the company (including onstage) for much of the decade. The pair had met in 1983, when the Australian designer, socialite and performer was the extravagant force behind Taboo club in London’s Leicester Square: a camper, druggier, more visually unhinged successor to Blitz. We get a vivid sense of Bowery’s contribution to Clark’s work in Charles Atlas’s fictionalized documentary Hail the New Puritan (1986), where Clark and his dancers are decorated (face and costume alike) with the polka dots then obsessing Bowery, who is an antic presence throughout the film. The final scene, in which Clark holds court among garish club personalities, is an apt summation of his position at that time, with ‘gimmicky’ subcultural signs threatening, deliberately, to obscure dance per se. (Clark in 1992: ‘I came through punk, where you used clothes as a weapon.’) It’s extraordinary to be reminded now how far these art-fashion monsters had penetrated the mainstream by the mid-1980s. Just as you might come across Bowery dressed as a ‘demented snowflake’ on the primetime BBC fashion programme The Clothes Show (1986–2000), so Clark was likely to turn up in the most pop of pop-cultural contexts – dancing alone in the dark in the video for Scritti Politti’s luscious 1984 single ‘Wood Beez’.

Such ubiquity is hard to imagine today for an artist with Clark’s ambitions and it’s clear that, to some degree, the contemporary art world has taken the place of pop music and broadcast media as the milieu in which his eclecticism can thrive. In 2001, Sarah Lucas contributed to the design of Before and After: The Fall; elements included underwear, fluorescent tubes and an enormous masturbating arm as the backdrop. Come, Been and Gone, created to celebrate the 25th anniversary of Clark’s company, was performed at the Venice Biennale in 2009. In 2010, the company had a residency at Tate Modern and, the following year, made th for the Turbine Hall, which featured music by Bowie, Kraftwerk and Pulp. The planned exhibition at Barbican – an institution with which Clark has had a long and productive relationship, notably including his ‘Stravinsky Project’ (2007), a trilogy of works based on ballets scored by the Russian composer – seems to affirm his mature and settled relationship with visual art and its ecosystem.

In truth, the relationship has always been there. From his time at the Riverside – where he and the artist Cerith Wyn Evans once bumped into Samuel Beckett in the cafe – Clark has treated art and artists with the same democratic connoisseurship as he has rock music or street style. You could consider his long-term artistic relationships as keenly felt counterparts to his balletic classicism. With certain departed figures (Bowery, Smith) excepted, many of these artists are still collaborators. Atlas and Wyn Evans were making visuals for Clark from 1981 onwards; Wyn Evans was later a member of Big Bottom, the bass-laden band that musician Susan Stenger put together to accompany current/SEE and later works. Stewart, of BodyMap, is still involved in designing for Clark’s choreography. Institutional settings aside, such relationships constitute the abiding sense in which you can still say that Clark is a maker of imagery and not only movement.

The Barbican show is due to present Hail the New Puritan as ‘an immersive film installation’, alongside works by Duncan Campbell, Peter Doig, Lucas, Silke Otto-Knapp, Wolfgang Tillmans and Wyn Evans. Here is an example of Clark’s art of attention that I hope makes it into the exhibition. He had been dancing to the music of T. Rex since at least the mid-1980s, but this particular moment was part of Michael Clark’s Modern Masterpiece (1991), which first toured in Japan and was then performed over nine consecutive nights, under the abbreviated title Mmm…, in a warehouse near King’s Cross, London, in June 1992. I was not there, so this is the version I know: Clark is on a garish Italian television show around that time, wearing a yellow dress over flared black trousers, and dancing to ‘Cosmic Dancer’ (1971). There is a moment when he pauses, almost facing the camera, for the line: ‘Is it wrong to understand the fear that dwells inside a man?’ On the record, there’s a little moan or sigh from Marc Bolan just after that line – Clark’s body flinches exactly on that ‘Oh!’ before he dances away again.

'Michael Clark: Cosmic Dancer' is at Barbican Art Gallery, London, from 7 October 2020 – 3 January 2021.

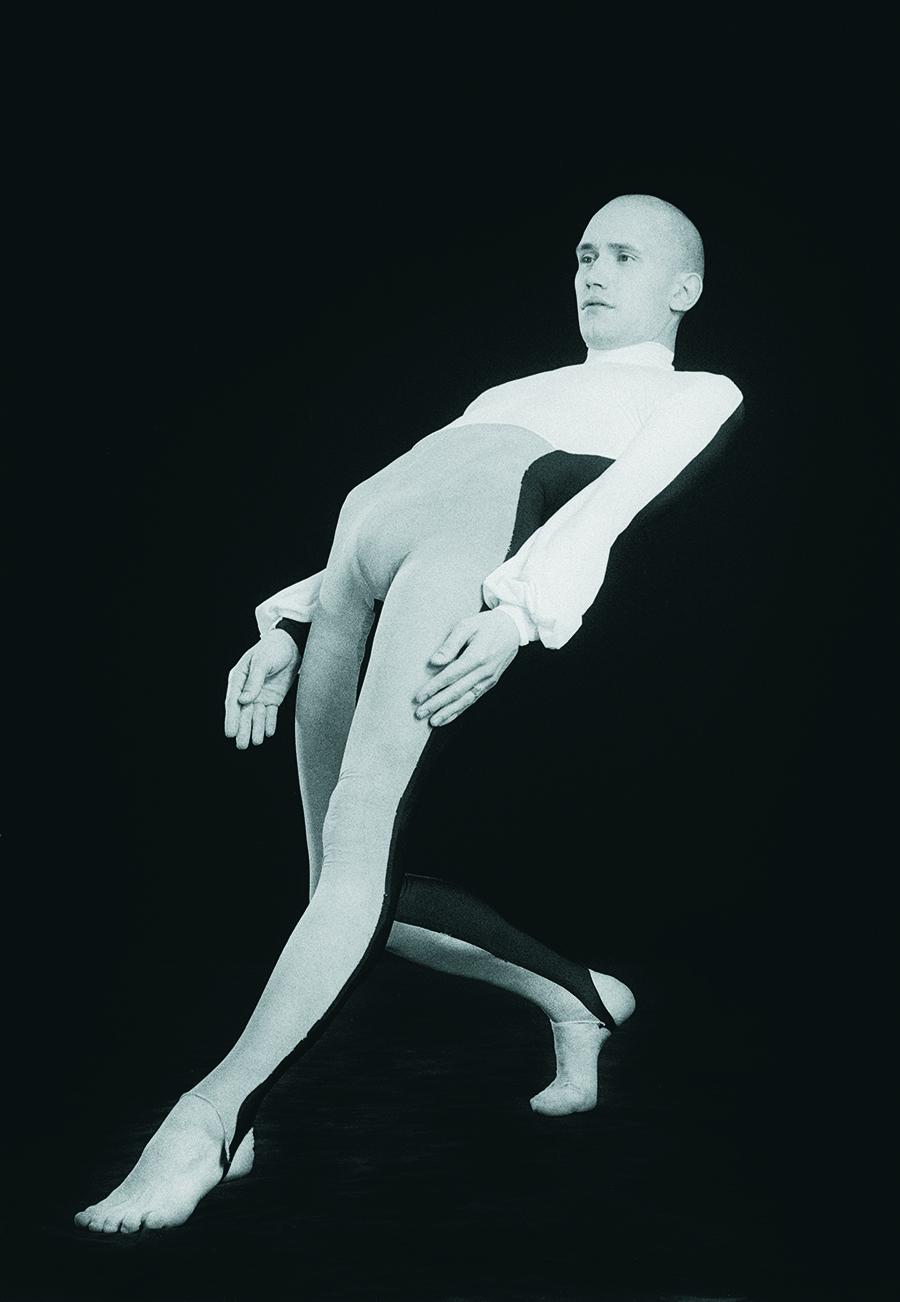

Main image: Charles Atlas, Hail the New Puritan, 1986, production still featuring Michael Clark. Courtesy and photograph: © Alexander James