Beverly Buchanan

Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA

Brooklyn Museum, New York, USA

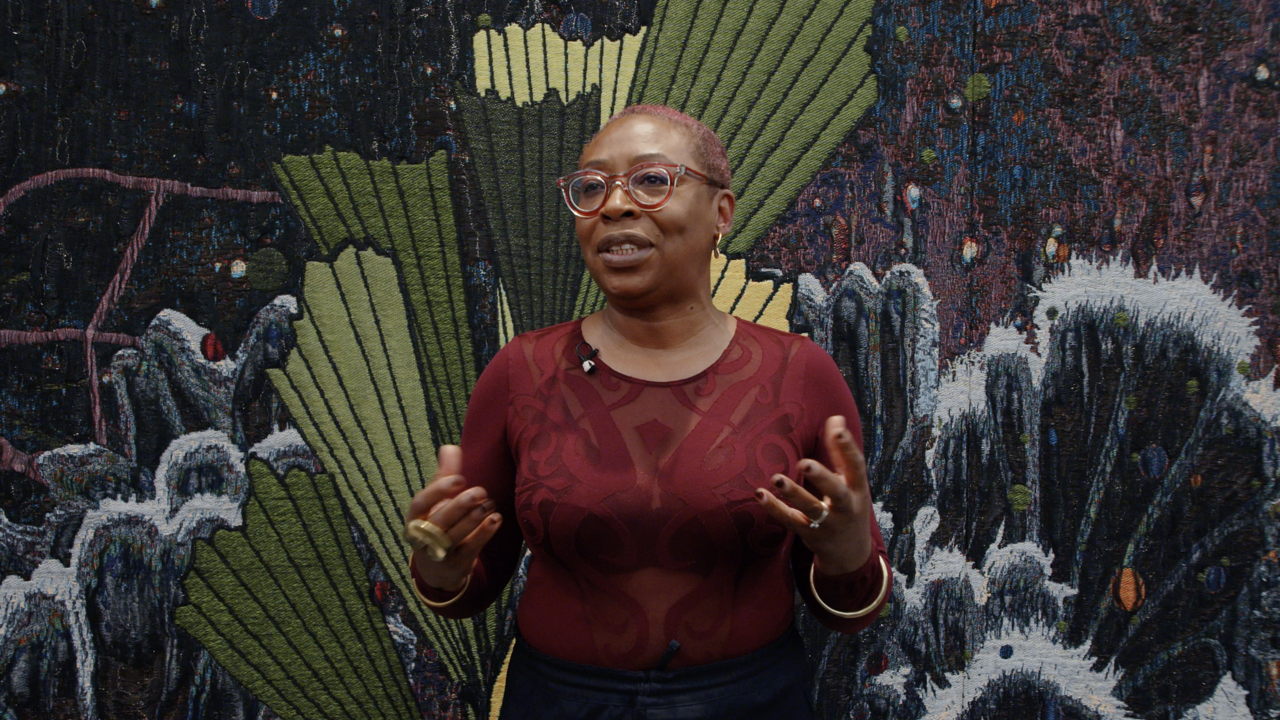

n 1977, at the age of 37, Beverly Buchanan decided to become an artist. At the time, she was working as a health educator for the city of East Orange, New Jersey. She already had a degree in parasitology and an offer to undertake her doctorate at Harvard, but she didn’t want to become ‘a doctor who paints’. As she recalled in an interview in 1993: ‘In spite of health problems and money problems that happened early, I said: “I’m still going to do this, because nobody’s asking me to do it.”’ ‘Ruins and Rituals’, the first show in a year-long programme of feminist exhibitions at the Brooklyn Museum, indicates the extent and depth of the artist’s commitment. Buchanan, who died in 2015, made work that moved across – or ignored the boundaries of – a variety of media, including drawing, painting, photocopy, photography, assemblage, sculpture and land art. Her attention to the rough, brick-and-mortar textures of the city or the non-conformist structures of vernacular architecture, such as barns and shacks built in the American South, intermingled with a lived politics of race, gender and memory.

The first elements that visitors to the show encounter are stone fragments: stacked on the floor of the gallery, pictured in various arrangements in black and white photographs, or documented in a video that moves between Buchanan’s extant, site-specific earthworks. To make the sculpture series ‘Frustula’ (1978–80), Buchanan poured concrete into moulds made out of old bricks, sometimes tinting the mixture with iron oxide and acrylic paint to achieve a reddish-brown hue. The resulting fragments sit somewhere between remnants of urban decay, ancient artefacts and art objects. But what does it mean to make – and not dig up or trip over – ruins? What is the fate of an object that begins its life as already destroyed?

Ruins signal that something, at some point, must have been created and used, before failing, then being abandoned or destroyed. Stones, in particular, stand as markers for absence and facilitate rituals, whether personal or collective, past or present. In The Writing of Stones (1970), philosopher-sociologist Roger Caillois described stones as possessing ‘a kind of gravitas, something ultimate and unchanging, something that will never perish or else has already done so’. If we look a little closer at Buchanan’s larger earthworks, documented in the exhibition, we come across subtle mnemonic demands and overlooked histories. In Marsh Ruins (1981), located in Glynn State Park in Brunswick, Georgia, inconspicuous mounds of concrete and tabby protrude like surfacing whales from within the surrounding grass. (Today, apparently, the work is in disrepair, therefore giving way to its own ruination.) To make tabby you need a large quantity of seashells, to which you add lime, water and sand. It is a cheap, yet labour-intensive, material and was therefore used widely in colonial America for building slave cabins and other structures (with slave labour). By creating ruins from tabby, Buchanan was reinstating a material history into the present as a means of accessing the politics of the past.

There is an intense sense of struggle and dedication in Buchanan’s art. In her dollhouse-sized wooden models of cabins – often painted, though burnt and buckling – the home becomes the embodiment of ingenuity in the face of poverty. Her images, while playful, dense and frenetic, appear hard-won. Standing in front of In the Garden (The Artist at Home) (1993), we see a doubled photograph of Buchanan, a self-portrait, looking out at us from the midst of thickly applied pastel scribbles. Her expression is defiant, yet open, as though she’s ready for a conversation.

Main image: Beverly Buchanan, Untitled (Double Portrait of Artist with Frustula Sculpture), undated, black and white photograph with original paint marks, 22 x 28 cm. © Estate of Beverly BuchananI