Brand, New

This year, the Billy Apple® brand turns 50. The artist formerly known as Barrie Bates talked to Anthony Byrt about a career of collaborations and controversies that has consistently redefined art’s relationships with advertising, science and technology

This year, the Billy Apple® brand turns 50. The artist formerly known as Barrie Bates talked to Anthony Byrt about a career of collaborations and controversies that has consistently redefined art’s relationships with advertising, science and technology

In 1959, Billy Apple – then known as Barrie Bates – left New Zealand to take up a place at the Royal College of Art in London, where he became one of the so-called Young Contemporaries alongside fellow students including David Hockney and Derek Boshier. But in 1962, Bates disappeared forever. He was replaced instead by a brand, Billy Apple, who went on to be a significant figure in New York Pop and Conceptualism. This year, the Apple brand turned 50. A survey exhibition is planned at the Auckland Art Gallery, New Zealand, for 2013, and art historian Christina Barton is currently writing the first major monograph on the artist’s work. I talked to him at his Auckland home.

Anthony Byrt On Thanksgiving in 1962, in a London flat, the 26-year-old artist Barrie Bates decided to change his name to Billy Apple. Fifty years later we’re still dealing with the ramifications of that decision – particularly the radical way it collapsed the line between art and life. What prompted it?

Billy Apple In 1959, I entered the Royal College. I’d never even had a camera in my hand in New Zealand but, by April 1960, I’d made the series of photographs ‘Art Declared Found Activity (Lathering and Shaving, Alicante Spain, April 1960)’. At that time, the New York School of painting was huge in London, but you could only see it in Grosvenor Square. At one end was the American Embassy. They had Barnett Newmans and Mark Rothkos, all that stuff. At the other, on the top floor of an apartment block, was Ted Power, who owned Murphy Radio and Television. You could go up to his place and see the American paintings he’d bought. There were all these British artists trying to make paintings that came up to the Americans’ mark. In the face of that, we tried to do something different at the Royal College. Eventually Lawrence Alloway [the British art critic and curator who moved to New York in 1961] pulled it all together.

AB You had a different methodology from many of your colleagues. Rather than making your work by hand, highly skilled technicians realized your ideas. At what point did you decide this was going to be your primary method of art-making?

BA I was in the graphic design school and thought about transferring to the painting school because that’s where all my friends were. The head of graphic design, Richard Guyatt, didn’t think that would be a good move. Instead, he arranged for me to have access to all the different departments so I could use their facilities. That was a key moment for my practice. I was able to go over to the sculpture school and get their foundry to cast my apples and peeled bananas. The graphic design school printed my canvases on their offset printing press. The ceramic school made the colour separations and offset plates for them, and so on.

AB Why did Guyatt let you roam?

BA I think he could see that I wasn’t like the other students. I was interested in ideas – the relationships between text and image, picture and headline. I was making a lot of posters for the rca’s jazz and film societies. Some of them were pretty bold. In 1963, I won the D&AD poster award with Join our Union, Jack!, which was for the ‘Young Commonwealth Artists 1962’ exhibition. But I didn’t actually work in the London advertising industry. The things I was doing were closer to an art context; works like Homonym [1963] in which I photographed two brands together that were completely different but had similar names: Batchelor’s Peas and Bachelor Cigarettes.

AB It sounds like you became an artist almost by default. But it’s also clear that your interest in the worlds of marketing, advertising and design was essential to your work.

BA Absolutely. And that’s how the brand came about. Advertising had a language that art didn’t have at the time, which gave it structure. It taught me that I could call myself an art director, and assemble a team of specialists to produce the work. The brand was also a way to get away from the New Zealand connection. Suddenly, you’re from nowhere, you’re brand new. I became British – I was created there in 1962. I could say: ‘Billy Apple was born in London,’ and a lie detector wouldn’t twitch.

AB You signalled this change by bleaching your hair and eyebrows with a modern, mass-market product: Lady Clairol Instant Creme Whip. There was also something very American about the name you chose. And then there’s the fact that it happened on Thanksgiving – which was serendipitous, sure, but still thoroughly American. Your early trips to New York were obviously very significant.

BA It’s as American as apple pie – like a product name. The London School of Economics was running charter flights, with cheap tickets to New York. I think David Hockney found out about them. David and I had friends over there that we could stay with, so we went. On the first trip in 1961, I was more interested in getting to know the superstars of the communication world, like Herb Lubalin, who gave me work experience in his office for a month. Herb was an amazing creative director and typographer. I learned how to make type talk from him. On the second trip in 1962, I made art contacts. Andy Warhol and I became good friends; we came from similar backgrounds, and immediately understood each other’s perspective. Andy introduced me to people like Henry Geldzahler and a wonderful young art writer called Gene Swenson.

AB Leo Castelli was also an important contact for you.

BA I met Leo in 1962, through Jasper Johns. Jasper rang him and said: ‘I’ve got Barrie Bates from London here,’ and I went to see him. He was very courteous. In May 1964, I visited him again. I was Billy Apple by then. In the office of the gallery, there was Leo, his right-hand man Ivan Karp and Robert Rauschenberg. I had a self-portrait on canvas with the front and back of my head printed on it, and a bronze apple. I rolled the canvas out across the floor and put the apple on the white area below, like a brand logo. Then Leo says, ‘Ivan, can you find Billy a place to stay?’ Ivan says, ‘Yeah, he can go to Eva Hesse’s.’ So I met Eva at her studio in the Bowery to go over details before she went to Berlin. And that’s where I moved. Leo was very kind and encouraging. I’d wanted to show with him right from the start, but in that period between May and August, he took on Warhol and James Rosenquist and there was no space left in his programme. He arranged for me to show around the corner with Bianchini Gallery. Ben Birillo was a partner in Bianchini, and was developing the exhibition ‘American Supermarket’ there over the summer with a lot of Castelli’s artists, and I was included. That was my entry into the New York art scene.

AB ‘American Supermarket’ was a hugely important moment. The show, which took the form of an actual supermarket, included the key figures of American Pop – Warhol, Johns, Roy Lichtenstein, Tom Wesselmann and so on. But, unlike many of those artists, you moved on from Pop quickly. An interest in science and technology became a major force in your work, and you started to collaborate with leading scientists and researchers. One of the earliest examples of this was your work with neon and lasers.

BA I was using light to develop an electric palette. A lot of people were using neon and fluorescent tubing at the time, but not many were making interesting work – with the exceptions of Dan Flavin and Chryssa. I moved on from neon to spotlights and lasers. If you take the glass away, all you’re left with is light.

AB Laser was a cutting-edge technology for the time. How did you get involved with it?

BA I got to know Dr. Stanley Shapiro in 1969. He was a pioneering physicist at General Telephone and Electronics Laboratories.

AB At your warehouse the other day, we unrolled a drawing from 1970, which documented you shooting a laser beam at the moon.

BA Stanley and I did that. We’d just finished de-installing Laser Beam Wall, which used a 100-milliwatt neon laser and convex front surface mirrors, at APPLE, my not-for-profit space at 161 West 23rd Street. There was this huge moon out the window. I said to Stanley: ‘Do you think we could do it?’ So he did some calculations and aimed the laser beam at the moon. We just turned it on and – phwooh! – there it was! With Stanley it was a bit like science fiction, Arthur C. Clarke or whatever. I remember him saying once: ‘Billy, we have a sodium laser that is invisible. But if I throw a chicken into it, it’ll disappear!’ He was part of that world; god knows what he knew about but didn’t tell me.

AB APPLE was one of the first alternative spaces in New York. Why did you set it up?

BA Dealer galleries wanted product, but a lot of us were gravitating towards making conceptual works. I had the front half of a space on 23rd Street as my office. I rented it off Sam Dorsky, of Dorsky Gallery. The Australian painter Brett Whiteley, who was staying at the Chelsea Hotel diagonally across the street, leased the back half as a studio. When he went back to Australia in 1969, I took it over. That gave me a place to do my own things. I knew people from Rutgers University, like Geoff Hendricks and Bob Watts. Keith Sonnier had been there too. They kept coming in, so I asked them if they’d like to do a work, and that’s how it happened. I wanted to call it 161 West 23rd, but when I was taking out free listings, the New York Times and New York Magazine found that too difficult. So I said to them: ‘Well, my name’s Billy Apple, and that’s how it became APPLE.’

AB Several alternative spaces emerged around the same time.

BA Yes, but we were probably the first ‘space’. Robert Newman had Gain Ground in his apartment. He was a good friend of Vito Acconci and John Perreault. Vito did the first works there. I think Eleanor Antin used it as well. Then, within about a month, APPLE opened. Others started to spring up like 112 Greene Street, which were pretty hefty. They had boards of directors, all sorts of things.

AB You were involved with 112 Greene Street too.

BA After I closed APPLE in 1973, Jeffrey Lew invited me to be the director there. I’d done the odd thing there myself, and he knew I could run a space. I did it for one season.

AB Why did you close APPLE?

BA These things have a certain energy. It had run its course, and I had enough confidence in what I was doing. I started showing at 3 Mercer Street, Clocktower, all those places.

AB It’s interesting that not long after you closed APPLE, you had a major survey at London’s Serpentine Gallery, ‘From Barrie Bates to Billy Apple’, in 1974. This looked at the way your practice completely dissolved the line between your art and your life, and also signalled the strong conceptual shift in your New York work. Everything you did was fair game: cleaning or subtly altering spaces, collecting broken glass, even recording your bodily functions.

BA We installed 12 years’ worth of printed self-portraits in the Serpentine’s main gallery. The British works in the show were various cast and printed body parts – my bronze throat, backside and index finger, my neon signature and early 1960s activity works, which were presented on jumbo-sized contact sheets. The American pieces included videos, my works with alpha waves and my tissue works, which documented nose-bleeds, excretory wipings, earwax extraction and semen. They were installed in the side room. Members of the public complained about them to the Metropolitan Police. The matter was referred to the Obscene Publications Unit and they told the Arts Council to close the place down. But it wasn’t just that. They wouldn’t put the poster for the show up around London either, the one we designed for the Underground.

AB Because it used the identity page from your New Zealand passport?

BA That’s right. The New Zealand government got involved and said: ‘Wait a minute, that’s our property, you can’t just do what you like with it.’

AB But the show reopened after a few days.

BA Norbert Lynton was the director of exhibitions for the Arts Council at the time. Norbert was a very intelligent man, and he became the mediator. He contacted me and said, ‘Look, we’ve got a problem.’ We had a meeting at the gallery. I made a couple of suggestions like we cover the windows or seal off the gallery. But nothing was going to work. Eventually, they left me no option but to remove the tissues. I had someone photograph me taking them down in order, and they went into a box with scraps of paper that documented the dates and times they were made attached to them. They’d been affixed with low-tack tape, which I left on the walls. Then I ripped the page illustrating those works out of the publication, wrote ‘Requested Subtraction’ on it with a big red marker, put the date on it, and taped it to the wall.

AB So you claimed the censorship as a work. What happened once the show was over?

BA We’d wrapped everything up when we got a call from Tate saying they wanted to look at the portraits. So we sent them over. They wanted to buy some of them, but the conservators said they weren’t stable enough. Well, the printing still looked pretty good when we unrolled them the other day. The linseed oil in the ink floats to the surface and puts a skin on it, like when you varnish a painting.

AB It sounds like almost everything that could have gone wrong did – the posters, the police intervention, the conversations with Lynton, Tate deciding not to buy the work. Where did all of that leave you when you got back to New York?

BA I basically went to bed for three months. I couldn’t believe it.

AB Meanwhile, you had to make a living. To do that you worked intermittently for many years in New York’s advertising industry, which was more important for your art practice than just a means to fund it.

BA When I moved to New York, it didn’t seem like a lot of art money was going round. I remember seeing a Lichtenstein painting in a Madison Avenue gallery in 1962 called Wow! for US$500. So I got a job with a company called Jack Tinker and Partners, which was a think-tank based in the Dorset Hotel, right next to the Museum of Modern Art. We never did advertising as such – we solved problems.

AB You went on from there to work as an art director with some of the major figures in Madison Avenue advertising, like Bill Bernbach and George Lois. The significance of your advertising work first dawned on me at your Mayor Gallery show in London in 2010, when I saw your piece The Hathaway Shirt Man [1964]. This used an actual campaign, but also used contemporary technology: it was a Hathaway advertisement xeroxed onto shirt fabric.

BA That’s an example of the way my art thinking fed my advertising, and vice versa. If I had worked for Ogilvy and Mather, who had the Hathaway account, I would have printed The Hathaway Man’s head on shirt fabric, just like that work. I printed that and other works in the lab at Xerox Corporation’s headquarters, for a show called ‘Apples to Xerox’ at Bianchini Gallery in January 1965. The show was Birillo’s idea. Xerography was breaking news at the time and here was Xerox, a big corporation, allowing me to use their newly developed technology to make my work.

AB How do you feel about your advertising work?

BA I think a lot of it is very clever. I always thought: well, they pay you for doing it, so it’s like a commission. I never thought I was doing my job and then doing art after work. Art was 24/7, and work fitted in with that. I also abused and used it: all the typesetting, all the wonderful photographers I could get to take pictures for me, all the colour prints and film and development and so forth.

AB I want to talk about one campaign in particular: Tareyton Cigarettes, which you worked on in the late 1970s.

BA I joined a boutique agency called Daniel & Charles. They were on a US$100,000 retainer with American Tobacco for a light version of Tareyton: low-tar, low-nicotine, the opposite of the harsh brands like Camel, Lucky Strike and Chesterfield. I knew about the black eyes Tareyton used in their ads and their line, ‘I’d rather fight than switch.’ I gave a new Tareyton girl a white eye instead and wrote: ‘We’d rather light than fight.’ I got Bert Stern to do the photograph, and we made the ad. In one year, the account grew to US$20 million, and went coast to coast.

AB It became an award-winning campaign. But you also showed work at Leo Castelli Gallery around the same time that seemed related to your ideas for the campaign.

BA I did Extension of the Given (Stairway Entrance) in 1977, in which I painted the gallery door’s arc solid white on the floor.

AB That arc is almost the same shape as the white mark you used in the Tareyton ads. So you took a highly conceptual work from the floor of an edgy New York gallery and turned it into a nationwide campaign for cigarettes.

BA I would get on the Lexington Ave subway line in the morning to go to work, and there in the subway would be this girl with a white eye holding a pack of Tareytons. So I’d be going to work looking at my work. I’d have a one-man show at the Canal Street station, then I’d get out at 42nd Street and there was the same image on a huge billboard.

AB Around this time – the late 1970s – you reconnected with New Zealand, except you were no longer the Barrie Bates who had left in 1959, but Billy Apple, American citizen and New York Conceptual artist.

BA I went to New Zealand in 1975 to visit family, and did a series of interventions in galleries and museums while I was there. Then in 1979–80, I did a more structured tour, which was about pointing out problems with gallery spaces. For example, if there was a pipe sticking out of the wall I’d paint it red, or give the gallery three options to correct it. The largest of these was Alterations: The Given as an Art-Political Statement (1980) at New Plymouth’s Govett-Brewster Art Gallery. I permanently altered the gallery’s central staircase. I wanted to carry out similar interventions in New York, so I’d propose projects to places like the Whitney and the Guggenheim, which the curators would consider. But because they were often perceived as criticisms of the institutions, they wouldn’t get carried out. I wasn’t interested in criticising them per se – I was interested in the neutrality of the white cube. Also around that time, New York was being taken over by European and American painters like Francesco Clemente, David Salle and Julian Schnabel. Conceptual practices just weren’t valued. So New Zealand was like having an alternative space: the rules weren’t so fixed, and there was a hunger for ideas. The opportunity to continue the practice was there.

AB As well as the architectural interventions, the other major conceptual strand to emerge in your work around this time was concerned with the ‘business’ of art. The ‘Transactions’ series first appeared in the early 1980s, and it’s still a major part of your work today. Did you also find a more supportive platform for those works in New Zealand?

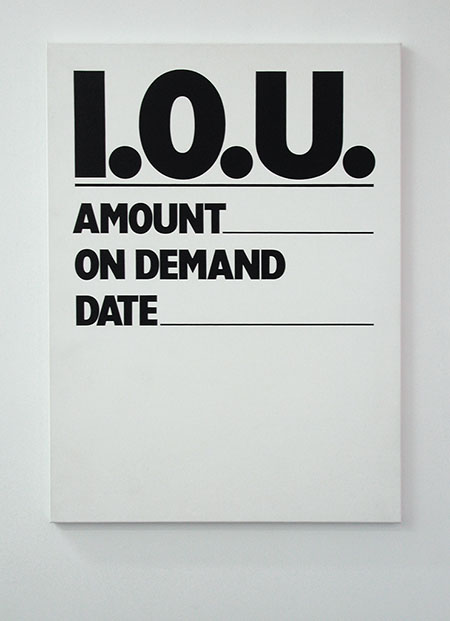

BA Yes. I was making conceptual and ephemeral works, but I needed money to survive. So I proposed an I.O.U work to Leo Castelli. Borrowing money would be the content of the work – a transaction between artist, collector and dealer. He said: ‘We don’t borrow money, Billy. We make money.’ On my 1979–80 tour of New Zealand, I had made a work for the University of Auckland called Numbered and Signed, to raise money for the Art History department. It was an edition of 25, and what people bought was a huge edition number and a signature. The Auckland art dealer Peter Webb was one of the co-publishers. Not long after, he asked me if I could do something he could sell. I told him I’d do an exhibition called ‘Art for Sale’, and each work in it would be called Sold. There were ten prints and one canvas. Each print cost NZ$300 and the canvas was NZ$3,000. It was what the market would bear – Peter had figured that out. I told him he couldn’t open until he had sold all of it. And he did. That was the first ‘Transactions’ show.

AB You also made a series of works titled ‘The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else’, in which people paid your bills.

BA I saw that series as a way to deal with daily life: rates bills, a battery for the car. It’s quite an interesting list when you put 50 of them up on the wall at one time. You realise we are described by the paperwork we generate. Mainly they were pretty everyday things: Nike trainers, or whatever. There was always hot smoked salmon [laughs]. My invoice would be attached to an A3 piece of paper with the word ‘paid’ at the top and the tagline ‘The Artist Has to Live Like Everybody Else’ beneath it. Collectors would pay my bill and pay for framing, and if a dealer was involved, pay the commission on top of that. What I got out of it was my bills paid.

AB You eventually made ‘I.O.U.’ works too.

BA The first ‘I.O.U.’ show was in 1988. I transacted an A3 print that said 'I.O.U’ for NZ$3,000. That became the benchmark. So, if you go up, A2 is NZ$6,000, A1 is NZ$12,000 and an A0 would be NZ$24,000. If you go down, A4 is NZ$1,500 and so on. Even today, they hold those prices; I can’t change them. Each one is a true contract. If it should fall into someone’s hands that I don’t know, that person can show up and legally demand the money from me, but they never do. I also made a series called ‘AC/DC’ [Artist’s Cut/Dealer’s Cut] beginning in 1986. The works were based on the dimensions of the golden rectangle, with a dotted cut line at the 61.8/38.2 mark: 38.2 percent was the dealer’s commission. It’s the ‘Divine Proportion’. I use this ratio as my business plan.

AB And the ‘From the Collection’ works, which you’re still doing, came out of this process?

BA The ‘Transactions’ were a step-by-step examination of the art business. First it was the space [the 1979–80 tour], then the purchase [Sold], then the commission [‘AC/DC’]. But the ‘From the Collection’ series was a true product. The first one was ‘From the BNZ Art Collection’, in the corporate colours of the Bank of New Zealand. Since then, it’s become a long list: corporations, private collectors, universities. I always use their corporate colours, no matter what they are.

AB That obviously ties back to your advertising work in New York.

BA That’s right. And it’s like my personal branding. It’s all very well changing your name, but you’ve got to reinforce that. So I made bronze apples. If you’re going to call yourself Billy Apple, what better way than to have an apple sitting there? I also made a poster for my 1963 show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Motion Picture Meets the Apple, in which I coloured my cheeks green and red. And when I did the original self-portraits, using Robert Freeman’s photos of the back and front of my head, I was looking at red and had green behind me. So I established brand colours. In recent times, I’ve been making a series of works called ‘Port and Starboard’, which also use red and green.

AB This seems a good moment to talk about your self-portraits. We unrolled about 40 at the warehouse recently, and I was instantly struck by how different they felt from the rest of your practice.

BA I made them all with Roy Crossett, who was the Royal College of Art’s printer. The first ones, from 1962, were pretty straightforward. I made them to acknowledge the name change. If you went to a good engraver for photo separations back then, you’d get progress sheets. You’d always get proofs of the separations: the cyan and magenta together, then the magenta and yellow, and so on until you got the final, complete image. I thought that aspect was missing from the 1962 portraits. So, in 1963, we did a progressive set, and it kept going from there. I did the last ones in 1974 for the Serpentine Gallery show.

AB Out of context, they’re quite beautiful. They look like paintings.

BA Well, they’re on primed canvas, so they do recognize portrait painting. They acknowledge the history of self-portraits. But it was just a mechanical process. The canvas had to be 36 inches wide because that was the maximum you could put through the machine. So if I bought a six-foot-wide roll of canvas, it was cut in half lengthways, then Roy and I would usually cut it into lengths of 48 inches, or sometimes five feet – whatever we needed.

AB But there’s a very real physicality to them which is totally different to a bronze apple, for example. This is the fundamental thing about the Billy Apple brand that I think most people miss. It’s one thing to launch a brand with a product – an object that can be marketed and sold. But it’s another thing entirely when the brand, its maker and its product are the same thing.

BA Would you like me to have a little ® tattooed on my arm or something? In fact, I’ve been thinking about this because I legally can – Billy Apple® is now a registered trademark. In 2007, my name and logo were registered in four commodity categories: Printed Matter, Clothing, Fresh Fruit and Orchard Services. We’ve just added two more categories. That formalizes the status of the art brand and gives me IP protection.

AB The trademarks seem like the ultimate self-portrait – a legal confirmation of your existence. But, over the past ten years, you’ve also been looking back a lot, reusing earlier works. The first time you and I worked together in 2003, for example, was on a project in which you re-created a 1969 work from APPLE and Extension of the Given (Stairway Entrance) from Castelli. Why is the earlier work circling back within your practice?

BA I use old works to come to new conclusions. It’s also very important to remind yourself of where you’ve been. Billy Apple turns 50 this November, but it won’t go on forever, and I’m very mindful of getting my affairs in order. And, as far as I’m concerned, these are new works. I’ll give you a couple of examples. My Wellington dealer, Hamish McKay, recently showed my 1961 canvas For Sale alongside AC/DC. The context is a commercial gallery, so I’m using these earlier works to revisit the same issues today. Hamish has one beautiful long, white wall in his gallery. I drew a 2B pencil line the full width of the wall, 5 feet 7½ inches from the ground, which was my height in 1964 when I first made that work, Wall Drawing (Head Height), in Eva Hesse’s studio. So, you can come back to these things.

AB On the one hand you’re getting your affairs in order, but the two projects I’ve been most interested in over the past few years, which are totally about the future, are the attempt to commercially grow a Billy Apple® apple, and The Immortalisation of Billy Apple®. Both projects have potentially enormous implications, and have taken a long time to develop.

BA We created a brand new cultivar, a new breed of apple with horticultural scientists. It was grown in three locations throughout New Zealand. It was a wonderful apple – it looked and tasted great – but it just didn’t have storage capacity, and in that sort of business when you’ve got to ship things around the world, it wasn’t viable. So we’ve shelved it. But I took a cast of it, and made sure we got some great apple works from it.

AB The thing I find fascinating about that project is not so much the international marketing of it, although that ties directly to the brand, but the idea that you could eat an actual Billy Apple – like we’re consuming a piece of the brand but also a piece of the body. The Immortalisation of Billy Apple project is interesting in this regard too, in that it uses your actual cells.

BA They’re in The American Type Culture Collection. A scientist can literally say: ‘I want some Billy Apple cells.’ They’re not coded for privacy like others. Dr. Craig Hilton and I have completed two stages up to this point. The first was exhibiting the cells themselves, to document the ‘immortalisation’ process in which a new cell line called Billy Apple® was produced. This was created by virally transforming my somatic cells so that they can live in a set of conditions that mimic the body. They were in a special incubator, and were kept alive by a huge bottle of CO2, which was painted green because that’s the colour of CO2. I’ve got very good stills of them, which are going to become a ‘From the Collection’ work – ‘From the American Type Culture Collection’ – which we’ll give to them. The next stage is figuring out how many of my cells it would take to make a one-metre cube. There’s a mathematical formula for this. It’ll be in the trillions. Just like any true immortalisation process, the project is ongoing, and could go on forever. It has no perceivable end, just like biotechnology has no perceivable limits.

AB The sheer fact that we could potentially use your cells to clone you, or consume an actual ‘Billy Apple’ proves that the brand is far more physically present and unsettling than its surface effects suggest. These ideas are just as ‘bodily’ as the tissues that were censored at the Serpentine Gallery: they’re all about things living, growing and changing. And, once again, it’s collaborations driving the work.

BA Sure. I need the expertise of lawyers, scientists and so forth to make works that are relevant today.

AB If anything, 50 years on from its birth, the brand is bigger than it has ever been. All of these recent projects – the registered trademark, the apple, the living Billy Apple® cell line – show that the brand has absolutely no intention of slowing down.

BA I’m too alive for that.

Billy Apple lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand. Selected exhibitions include: ‘American Supermarket’, Bianchini Gallery, New York, usa (1964); ‘From Barrie Bates to Billy Apple’, Serpentine Gallery, London, uk (1974); ‘Alternatives in Retrospect’, New Museum, New York (1981); ‘Selected Works 1962–74’, Leo Castelli Gallery, New York (1984); ‘As Good as Gold: Art Transactions 1981–1991’, Wellington City Art Gallery, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, and Auckland City Art Gallery, New Zealand (1991); ‘Toi Toi Toi: Three Generations of New Zealand Artists’, Museum Fridericianim, Kassel, Germany (1999); ‘Shopping: A Century of Art and Consumer Culture’, Schirn Kunsthalle, Frankfurt, Germany, and Tate Liverpool, uk (2002); Andy Warhol Museum, Pittsburgh, usa (2003); ‘Billy Apple®: A History of the Brand and Revealed/Concealed’, Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, the Netherlands (2009); and ‘Billy Apple®: British and American Works 1960–1969’, The Mayor Gallery, London (2010). A retrospective of his work will be held at the Auckland Art Gallery in 2013.