Bleak houses

Paul Noble

Paul Noble

Somewhere in almost every public building there's a wall or cubicle door inscribed with a lone swear word.

There's something funny about the dumb incongruity of a shit-saying utilitarian surface, and most of the time these dirty protests make melaugh. If I'm feeling a bit angst-y though, I remember The Catcher in the Rye (1951) and, like J. D. Salinger's young narrator, begin to think theworld would be a better place if only I could scrub the wall white again.

I'm not sure what Holden Caulfield would make of Nobson, Paul Noble's project for an English new town. The public buildings aren't scratched with swear words - it's not that kind of place. Some of them are swear words though; profanities for living in. Lurking behind thewashrooms of Nobson's Public Toilet (1999), a line of stalls spell out 'Fuck Me Fuc' in a blocky typeface addressing the heavens. The sentence is missing a K-shaped cubicle, as if the builders downed tools and ran at the rumble of an approaching aerial censor. Smudged andseamy, the toilets' windows might veil a thriving cottaging industry, where slack-skinned citizens explore the blunt contours of each other's pencilled bodies. Noble never shows us the burghers of Nobson, though, and his alphabet buildings are the only vital signs in a chilly grey landscape.

Nobson Newtown has 27 buildings and places. Some of them sprawl across his huge drawings, light winking from their hard graphite lines. Others - the sculpture park, the jetty, Ye Olde Ruin - squat in Noble's imagination, awaiting planning permission. Most of Nobson's structuresare fabricated from stone-hewn letters, 3D Scrabble tiles describing what goes on inside. There's a rewiring of Modernism's form-follows-function credo here, with the word for a thing dictating whether it looks good or can get the job done. This can feel a little sinister, especially among the sludgy vowels of the purpose-built Nobslum (1997?8). Local authorities regularly green-light sink estates, but few have the balls to designate them slums before the lino has been fitted. Who'd condemn tenants to shuffle through the awkward 'N' and the claustrophobic 'L'?

Who'd live in a house like this? Maybe the point of Nobson's buildings is to ease you into the words themselves, to give visual weight and texture to verbal concepts. They're not a straight conflation of signifier and signified (Ferdinand de Saussure isn't welcome in the Nobslum), but they share something with the inky brushstrokes of a Chinese ideogram, in which the world and the word blur into anoddly poetic hybrid.

If language was a place, it would be a made-up somewhere, an allegorical fiction like C. S. Lewis' Narnia. A place a lot like the real world, then, but fantastical enough to comment on quotidian things. Compelling parallel worlds are rarely heaven on earth, and language is good at resisting shiny-eyed revolutionaries. Shrugging off Esperanto and Shavian spelling, it has retained an unpredictable, human sort of magic. Noble's decaying alphabet city isn't a Utopia - it isn't even a nice spot - but it revels in the fact of its own creation. There's something boyish in the obsessive detail of Nobson Newtown, with its ruled lines and precision shading. In their complexity at least, Noble's drawings are like the sandcastle you promised yourself you'd build when you grew up, that shimmering confection of towers and turrets that flashed across your mind's eye. Engaging images can look tiresome to make - a Vija Celmins starscape, say, or the chequered floor of a Pieter de Hooch - but Noble's work hums with contented industry. The careful delineation of Nobson's territory is pretty satisfying for the viewer too. Drawn in Atari aerial perspective, the town resembles the background of an ageing arcade shoot-'em-up. Computer games don't just grab us through blistering button pushing; we've always got half an eye on the incidental polygons of the scenery. Nobson is all backdrop, all tiny motifs and credibility-building detail. Without a joystick and power-ups it's never 'game over', and we start to think hard about Noble's deserted cityscapes.

What kind of town is Nobson? Somewhere where work is valued, or at least the subject of rumours and speculation. C.L.I.P.O.N (1997), an acronym for the Chemical and Light Industrial Plant of Nobson, is a smokestack mess of pipes, gantries and belching flues. It looks functional enough, but it's worth checking the small print. Noble's Introduction to Nobson Newtown (1998), a pocket-sized parody of a faintly worthy heritage guidebook, tells us that 'there is no chemical industry in Nobson, and virtually no light (let alone heavy) industry either'. Perhaps the plant is a monument, a conceptual model of work decked out with plenty of authentically steaming chimneys. Art was offered as a panacea for poverty in late 1990s Britain, with a rusty angel blessing Gateshead's abandoned collieries and a neon scribble beaming down on Hackney's unemployed, claiming 'Everything is Going to Be All Right'. C.L.I.P.O.N doesn't deal in that kind of spiritual sublimation, and the idea of joblessness lingers in the soothing balm of cultural regeneration. Nobson's singular taste in memorials extends to Nobson Central (2000), a demolished neighbourhood disfiguring the town centre like a picked-at scab. It has a metro station, although it's hard to imagine day-trippers strolling through the bin bags, broken glass and weird, cloacal forms that nestle among its busted buildings. Introduction to Nobson Newtown calls this wasteland an expression of the belief that 'the only perfect thing is a flawed thing'. Maybe, but the guidebook's narrator is pretty unreliable, an imaginary local history buff fabricating facts from sparse parish records.

Nobson Central feels more concerned with the strange aesthetics imposed on poor people in big cities, the search for beauty in grubby peripheral boroughs. The best stuff is always in the town centre, on tree-lined streets where people wear hand-tooled shoes. Most of us can't afford to live there though, so we try to find patterns in stained concrete and flowers in dog-shit parks. Nobson's dilapidated heart is an Ur-periphery; a wrecky collision of Hoboken, Aubervilliers and Walthamstow ripped up and dumped on an elegant network of boulevards. Stuck in the middle of town, our downsized taste isn't some bucket-shop deal with beauty. Flaking plaster becomes an aesthetic choice, and bent girders start to look like a quiet revolution.

The more I look at Paul Noble's drawings, the less they add up to a conventional dystopia or an uncomplicated thumping of post-war town planning. His ghost town is haunted by horrible locations - Nicolai Ceausescu's Bucharest and the prosaic Legolands of Stevenage and Luton - but it's got room for friendlier apparitions too. One drawing contains a couple of Friesian cows standing nonchalantly in an enclosure hung with lolling bunting. There's something not quite right about these heifers: in the place of their faces they have mooning yin-yang symbols, matching the black and white marking of their hides. Somehow, they still look like ordinary cows, and this curious fact echoes through Noble's entire project like a low-decibel moo. If we see these creatures as just cattle, how does that fit in with the vague thoughts they trigger about cosmic vegetarianism and Milton Keynes? What kind of information is Noble giving us?

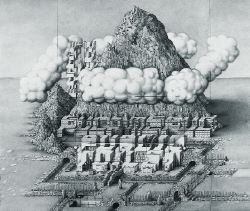

Nobson's wordy buildings pose similar questions. We're a bit anxious to ring their doorbells in case they're not architecture after all but ideas to inhabit - albeit ones with slippery floors. Acumulus Noblitatus (2001), the home of the holy herd, develops the social critique of Noble's earlier work into something knottier, but a little more hopeful. Beneath a range of mountains surrounded by tree stumps sits a cluster of buildings spelling out 'Squat'. The owner must be a benevolent guy, or at least resigned to his fate - anyway, the squatters have made it look homey. There's a kitchen and a rooftop fishpond, even a mausoleum decorated with a wreath shaped like the anarchy logo's circled 'A'. It could be a letter of protest - there's no 'A' in 'Nobson Newtown', but different twists on logic seem welcome in this area of alphabet city. A bicycle-driven printing press is parked in the devastated landscape, ready to pump out radical pamphlets. If it was the squatters who harvested the forest, at least they've made an attempt at a sustainable logging. Schematic oaks rise from the ground, paper shapes cut with blunt-nosed scissors. Like lots of things in Nobson, these trees have an odd existential status. Fashioned from something they're supposed to represent, they have the wobbly ontology of a sculpture of a boulder rendered in stone. Look closer and it appears that tiny leaves have fallen from their pulpy boughs. It's a detail that throws you back on yourself, leaving you suddenly aware that you've been spinning stories about a place that doesn't exist.

When we're looking for answers, it seems right to turn our eyes towards the sky. If we could walk around Acumulus Noblitatus, we'd pass over a cock-shaped bridge with a glistening glans, past a deserted tea party and a turnip patch, and maybe wind up among some odd, wind-carved rock formations. Standing on higher ground, squinting against the sun, we'd see that they formed an eroded text. If we knew our history, wemight recognize it as the words of Gerard Winstanley, a big cheese in the proto-socialist 17th-century Digger movement: 'And the nations of the world will never learn to beat their swords into ploughshares, and their spears into pruning hooks, and leave off warring, until this cheating device of buying and selling be cast out among the rubbish of kingly power'. We'd try to square Winstanley's words with the Nobslum and C.L.I.P.O.N. and the dirty little class war they imply, but it wouldn't compute so we'd look up and see a range of cloud-choked mountains skimming the sky. Our minds buzzing with cows and trees, with lewd loos and fallacious factories, we'd suddenly experience a moment of clarity: reality is ours for the shaping. It's only when we reach the summit of Alexandro Jodorowsky's Holy Mountain (1973) that the director reveals the answer to life, the universe and everything: 'If we have not obtained immortality, we have obtained reality. But, is this life reality? No, it's a film, Zoom back camera! We are images, photographs. We must break the delusions! Peace on Earth! This is Maya! Enough for the Holy Mountain, real life awaits us!'

We may lose ourselves among Noble's teeming drawings, but their best trick is to undermine the pencilled fantasy of Nobson Newtown and push us back into everyday life, where we can do something about poverty and unemployment, about razed forests and ugly public housing. Maybe I'll start small. Someone's written 'fuck' on a desk in my local library. It wouldn't take long to scrub it off.