Brian Dillon's Fan Letter to Writer Ian Penman

Found first in the pages of NME, an homage to the critic who brought an antic traduction of high French theory to the study of contemporary pop

Found first in the pages of NME, an homage to the critic who brought an antic traduction of high French theory to the study of contemporary pop

‘The song has to read like a love letter, from miles away.’ There are writers who rush at the empty page or screen without a thought for precursors, who don’t need to hear the intimate whisper of influence in order to get started. I’m not one of that independent breed. When I began writing for a living, 18 years ago, it was with a stack of predictable heroes at hand: Roland Barthes, W.G. Sebald, David Foster Wallace. Mascot, talisman, charm or counter-charm: the constellating habit has stayed with me, if not this precise canon. Today, when stuck, I’ll more likely mutter to myself certain spell-like passages from Joan Didion or Elizabeth Hardwick. But, all the while, Ian Penman – critic, essayist, mystical hack and charmer of sentences like they’re snakes – is the writer I have hardly gone a week without reading, reciting, summoning to mind. The writer without whom, etc.

Actually, my debt to Penman is even older and deeper. Readers my age found him first in the pages of the NME, where he brought an antic traduction of high French theory to the study of contemporary pop. I was young enough, and late enough to the IP cult, to have culturally missed the post-punk cusp of the 1980s, a moment now much venerated. In place of awkward, fractured thought and musical texture, mid-1980s pop was a mannerist shimmer – so, too, the language (approving or aghast) required to describe it. Penman’s criticism read like his own description of the music of Kid Creole, with whom he was improbably obsessed: ‘You have to choose your words carefully, carnally; you have to find a crucial metaphor.’ I was 15 when I first read Penman, and practically all I thought about was music. After Penman, I thought about language, too. About the ways a young life might be diverted by the wrong words, the wrong metaphors – how you might find the right ones in a stray song lyric or the corner of a magazine page.

Penman turned me from a dutiful reader into a dazzled one and led me to the library in search of Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Pauline Kael and Susan Sontag. An ambiguous list: some idea of criticism strung between the scholarly and the demotic, avant-garde and pop. For a time, theory won out. I went to university to study literature and philosophy, almost forgot about Penman except on the rare occasions I could afford the glossy magazines where his byline now appeared. Nearly a decade passed until, in another country, in the middle of a breakdown, I read an autobiographical essay by Penman in the December 1997 issue of Arena magazine. ‘Heroin: A Love Story’ is one of a handful of great magazine pieces I could quote you from memory, with its ‘long slow plummet of a tale, a decade-long home disaster movie flickering away always now behind my heavy blue lids as I jerked awake on shivery breakers each morning and crashed asleep in luminous disarray every night’. I read this piece just as I realized my own life had taken a dismal turn, realized too that writing might be an escape route, into a richer and stranger existence. Suddenly, here was Penman again, showing the way with his high-low swerves from seminar to street, his vivid word choices (often straight from the esoteric 17th century) and, most of all, his startling metaphors. Penman on melancholia, in 2001: ‘Art is a field alive with sun motes and glyphic rooks; depression is the severed ear.’

‘In Penman’s writing, decades of love and listening translate into prose that glides and shimmies and pivots on risky metaphors, low puns, highbrow reference points.’

Penman the music critic had not gone away, though he seemed now, even more than in the 1980s, to be both of his time and out of it. There had been long, rapt and sedulous essays on specific artists and some of these (on John Fahey, say, or Tim Buckley) were collected in his 1998 book Vital Signs. He had always been just as compelling at capsule-review word lengths or abstracted into polemic essay mode, as in a state-of-the-pop-nation NME piece from 1984 – I read it dozens of times – where he tried to describe what he was hoping for in music: ‘an unconscionable swerve, heretical detail, some shiver of incomprehension’. The full range of Penman’s occult thought and vagrant taste seemed to be expressed in a Wire piece on Tricky’s Maxinquaye in 1995: ‘Forget the centre: the margins are where the signals are coming from. Everything is velocity and disappearance and mutation.’

Nowadays, Penman’s writing mostly appears in the London Review of Books (LRB), where his bio tells us he is working on a novel about music and terror in the 1970s. I dearly hope he, or some canny editor somewhere, is also planning to make a book out of these LRB pieces, which are some of his best, whether he is hymning the work of Kate Bush, Charlie Parker or Frank Sinatra – or expressing unpopular ambivalence about David Bowie or Patti Smith. Perhaps it sounds like an antiquarian pursuit, this recasting of the canon. But the writing is frequently something entirely else: decades of love and listening translated into prose that glides and shimmies and pivots on risky metaphors, low puns, highbrow reference points. Here he is on Parker: ‘Unearthly sonic signatures woven from everyday air; flurries of notes like Rimbaud’s million golden birds set free: no one else could do this one thing he did, exactly the way he did it.’

In his fan letter of a book about John Updike, U & I (1991), the novelist Nicholson Baker rejects the idea that there are aphoristic lessons hidden in the master’s work and, instead, wants to follow ‘the trembly idiosyncratic paths each of us may trace in the wake of the route that the idea of Updike takes through our consciousness’. Isn’t that what fandom and influence (if such exists) feel like? Who knows if Penman thinks of his work in anything like the ways I do – a handful of emails aside, we have not met – but I wouldn’t have written a word without the dream, ghost, echo of his writing.

First published in frieze, issue 197, September 2018, with the title The Crucial Metaphor.

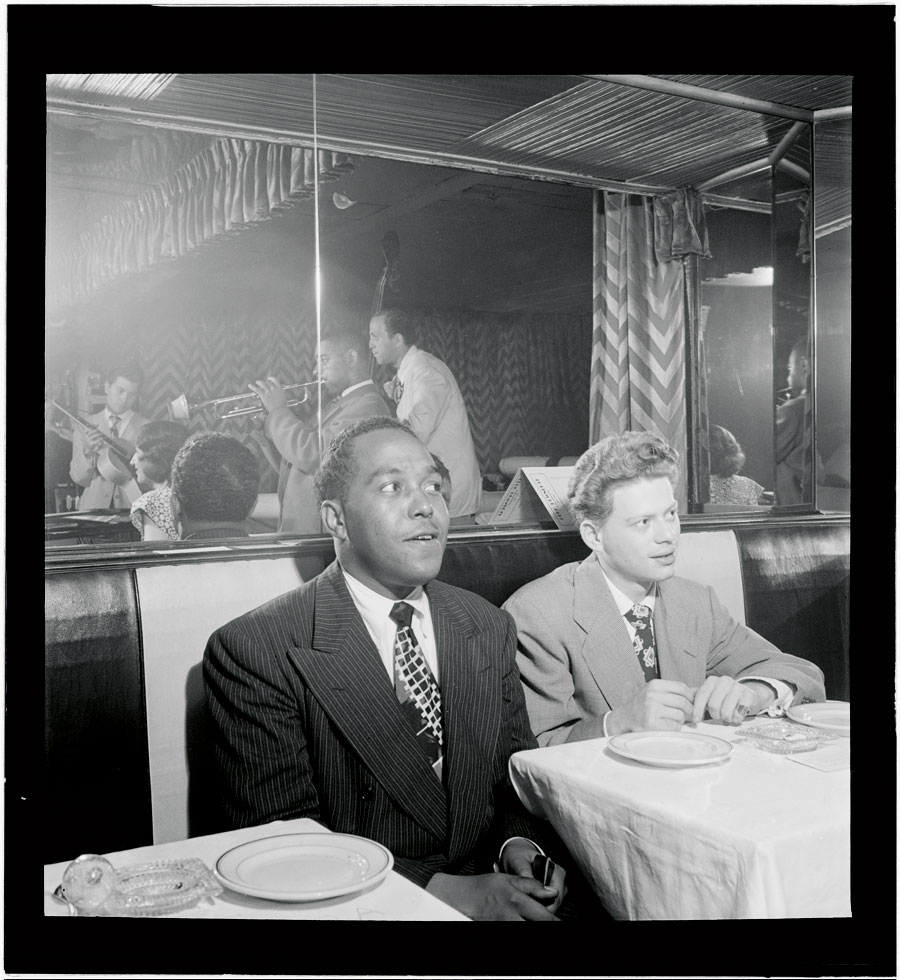

Main image: Ian Penman (right) with Mayo Thompson from the band Red Krayola, 1981. Courtesy: Getty Images; photograph: Jill Furmanovsky