Charlotte Prodger Wins 2018 Turner Prize with iPhone Film Exploring Queer Identity

The artist used her acceptance speech to emphasize the importance of public funding for the arts

The artist used her acceptance speech to emphasize the importance of public funding for the arts

Glasgow-based artist Charlotte Prodger has been awarded the 2018 Turner Prize for an exhibition at Bergen Kunsthall in Norway comprising two films, one of which was shot entirely on her iPhone and recalls the artist’s experiences of coming out in rural Aberdeenshire in the 1990s. Prodger is set to represent Scotland at next year’s Venice Biennale. The Turner Prize – founded in 1984 – is awarded to a UK-based artist or collective each year.

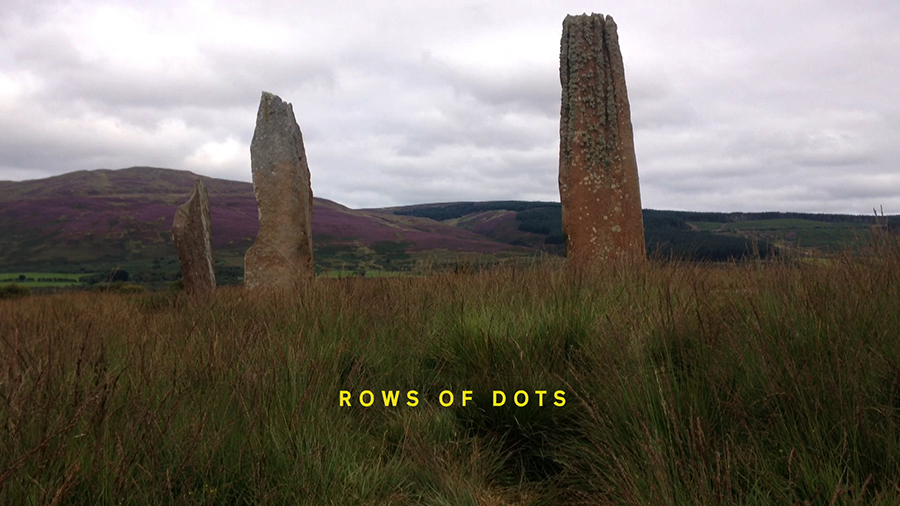

Prodger was commended for two videos, Bridgit (2016) and Stoneymollan Trail (2015): the former was filmed on her iPhone and includes the artist reading passages from her diary. Bridgit, which Prodger has described as being about fluidity of identity from a queer perspective, includes footage of Neolithic standing stones in rural Aberdeenshire, shots from inside her Glasgow flat and sequences from a ferry crossing. Prodger has described the iPhone as functioning as prosthesis, with the smartphone becoming an extension of her own body.

In a 2014 interview with frieze, Prodger spoke about what it means to make queer art now. ‘Ultimately, queerness is not a category or a style but a lived experience, which I feel is in danger of being colonized, of being sanitized, made digestible, hip, hilarious. The trend, which has great currency in the art market just now, of artists who may not identify as queer but are flirting with a ‘gay aesthetic’, is divorced from the actual lived experience of being a queer person in the world,’ she told us. ‘Provincial and rural queer narratives feel important to me in this respect, as subjectivities that exist outside the liberal urban context.’

Writing in frieze, Erika Balsom expressed her enthusiasm for the artist’s films: ‘Prodger articulates an approach to personal filmmaking that is as intelligent as it is moving, using an iPhone camera to tackle problems of autobiography and authenticity in ways that today’s legions of personal essayists and selfie obsessives would do well to learn from,’ she wrote.

‘When the self is everywhere for sale, quantified and optimized for productivity, Prodger proposes another way of conceiving of what it is to be an ‘I’ in the world, confronting otherness within and without. Of all the artists in this absorbing exhibition, she is the one who offers the greatest challenge – and the greatest reward,’ Balsom argued.

Tate Britain director Alex Farquharson, who chaired the judging panel – which this year was comprised of Oliver Basciano, Elena Filipovic, Lisa Le Feuvre and Tom McCarthy – said Prodger’s work showcased the ‘most profound use of a device as prosaic as the iPhone camera that we’ve seen in art to date,’ and that the jury decided Bridgit was ‘incredibly impressive in the way that it dealt with lived experience, the formation of a sense of self through disparate references.’ ‘It ends up being so unexpectedly expansive. This is not what we expect from video clips shot on iPhones,’ he continued.

All four artists nominated for this year’s prize work with the moving image, and frequently touch on political themes. Forensic Architecture, the Goldsmiths College-based research agency, presented work investigating a Bedouin community being cleared by Israeli police; Naeem Mohaiemen exhibited two 90-minute films, including one about a man living a solitary existence in an abandoned airport; and New Zealand artist Luke Willis Thompson presented a series of films, which sparked controversy for allegedly turning Black suffering into spectacle in his silent film portrait of Diamond Reynolds, Autoportrait (2017).

Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie announced the GBP£25,000 prize at an awards ceremony at Tate Britain, London. Speaking after the announcement, Prodger said: ‘I feel very honoured, blown away really. It’s quite surreal. It feels lovely.’ When asked what she would do with the prize money, she replied: ‘I’ll live on it. I’ll pay my rent and my studio rent and some bills. Maybe there’ll be a little treat […] probably a nice jacket. Don’t hold me to that!’

In her speech, Prodger also cited the importance of public funding for the arts in Scotland: ‘I wouldn’t be in this room were it not for the public funding that I received from Scotland for free higher education and then later in the form of artist bursaries and grants to support not only the production of work but also living costs,’ she said.

Tate’s director, Maria Balshaw, also used the awards ceremony as a platform to speak out about current political issues, including artist Tania Bruguera’s arrest for a protest in Cuba, and the damning evidence revealed in recent reports on the value of the arts in British education: ‘Because art is not sufficiently valued, young people feel they can’t risk choosing to study art, and state-funded schools struggle to create the time for them to do so,’ Balshaw said. ‘The result has been a steady decline in the number of students who enrol for arts subjects.’

Main image: Charlotte Prodger, 2017. Courtesy: Tate