Left Behind?

Naeem Mohaiemen’s films reflect on recent histories of the global radical Left

Naeem Mohaiemen’s films reflect on recent histories of the global radical Left

Naeem Mohaiemen was born in London in 1969, to Bengali parents. In 1970, his family returned to what was then East Pakistan, just before the outbreak of the 1971 war that split the country and birthed Bangladesh. Mohaiemen grew up in tandem with the newly formed state. Bangladesh’s early years were marked by a series of political coups as the Left struggled with more conservative groups over the ideological direction of the nation. The history of these years and the failures of 20th-century Leftist movements globally fuel Mohaiemen’s films and writing.

From 2001 to 2006, he was a member of Visible Collective, a group of artists, activists and lawyers whose projects drew attention to the impact of racial-profiling on Muslims following 9/11. He has since become a member of the Gulf Labor Coalition and a key contributor to negotiations with the Guggenheim for fairer conditions for the workers building the museum complex on Saadiyat Island in Abu Dhabi.

Politics are urgent in Mohaiemen’s films, although he is careful to make a clear distinction between his activism and his art. In the four-film series ‘The Young Man Was (No Longer a Terrorist)’ (2011–16), pivotal moments in Bangladesh’s history collide with global geo-political events. Together, United Red Army (2011), Afsan’s Long Day (2014), Last Man in Dhaka Central (2015) and Abu Ammar Is Coming (2016) connect young, Leftist men who represent the country’s ideological journey through the 1970s: soldiers who attempted a local coup during a global hijacking; activist Afsan Chowdhury, whose Marxist library almost cost him his life; journalist Peter Custers, who became involved in underground politics; and Bangladeshi men who, perhaps, joined the Palestine Liberation Organization.

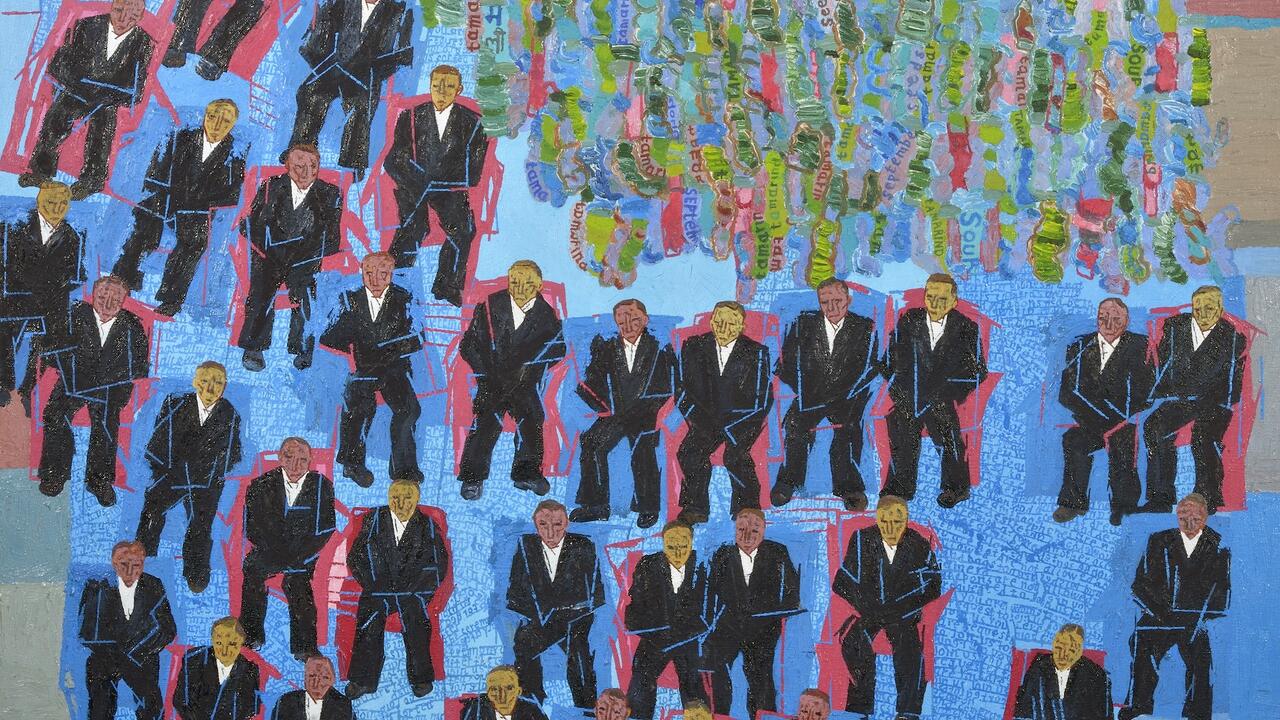

Two new films, shown at last year’s documenta 14, branch out in new directions. Presented in Kassel, Two Meetings and a Funeral (2017) extends Mohaiemen’s interest in the multiplicity of perspectives surrounding historical events. The three-channel film focuses on the 1973 Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) conference in Algiers – a key moment in Bangladesh’s ideological shift from socialism to Islamism. Combining contemporary footage with interviews and archival material, the images double and triple in dizzying ways across the three screens in a flow as complex and slippery as the affiliation, in NAM, between a group of nations with vastly different histories and conditions.

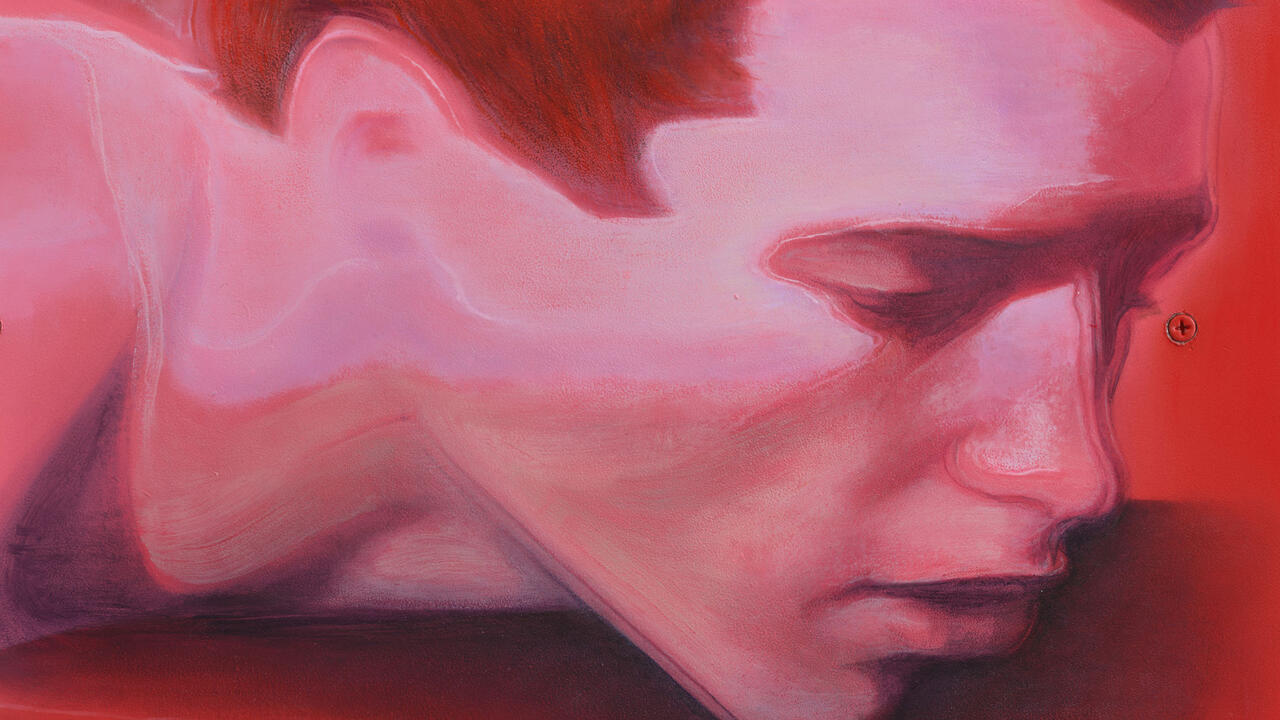

In Athens, Mohaiemen premiered his first fiction feature, Tripoli Cancelled (2017). In the terminal building of the city’s disused Ellinikon airport, designed by Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, a lone man lives out an endless exile. He spends long stretches of time looking out across the bright sunlit tarmac. With nothing but haze visible beyond the airport’s borders, the protagonist exists in a dream state on the border between reality and insanity. Loosely based on an incident in which Mohaiemen’s father lost his passport and was stuck in Ellinikon airport for nine days, Tripoli Cancelled astutely captures the state of interminable displacement that characterizes the 20th and 21st centuries – a time of migration, exile, refuge and waiting.

Although his subjects are often idealists with failed dreams, Mohaiemen is optimistic about the future. By looking back to historical pivot points, he gestures towards trajectories not taken to ask: ‘What if?’ Right now, it feels like an important question.

Sarinah Masukor How did your commissions for documenta 14 come about?

Naeem Mohaiemen I had been working with Adam Szymczyk since 2014. My solo show ‘Prisoners of Shothik Itihash’ was the last exhibition he curated at Kunsthalle Basel before he began as artistic director of documenta 14. Over the past three decades, documenta has developed a reputation, certainly among artists, for combining an innovative formal approach with a legible political project, so the crises ricocheting around the world were part of our ongoing conversations. Within that framework, I proposed the film that became Two Meetings and a Funeral.

SM You were originally going to make just one film?

NM Yes. Two Meetings and a Funeral follows the four films of my earlier project, ‘The Young Man Was’. They are about a certain form of doomed masculinity on the margins of Leftist movements that are trying to get to state power, usually through insurrection. In Two Meetings, I wanted to look at what happens when forms of the Left actually do get to power.

The 1970s were the twilight of world socialism and communism. One of the many reasons to look at that moment is to parse some of the ways that previous Leftist political projects went terribly wrong: they metastasized into totalitarian governments; redistribution created new elites and forms of control; productive units were destroyed in the rush to ‘catch up’; mineral wealth artificially masked structural weaknesses; and, of course, there were ferocious forms of pushback through hot-cold wars, cross-border sabotage and population control.

SM How did the idea for Tripoli Cancelled emerge? It’s a very different project from your previous films, though there are some thematic continuities. Did you know you wanted to make a fiction film?

NM There are fictional elements in both Afsan’s Long Day and Abu Ammar Is Coming. The narration slips outside of the facts but, because those flickers are sandwiched between actual events, audiences sometimes assume it’s all documentary – and I don’t feel I have to underscore which parts are fiction. It’s how I write the script.

SM John Akomfrah also filmed The Airport [2016] at Ellinikon. Both films elegantly capture the last moments of Saarinen’s building, which might not exist much longer.

NM If you go to that airport, people are compelled by similar elements: the vast balcony and stairs going down to the empty shell, the bar, the control tower and the runway. When the airport was functional, none of these areas were empty; they were full of ticket counters, machines, chairs and, of course, people. In The Airport there are mythical figures – the astronaut, the passengers, the dawn-of-time ape. In mine, there is one person – a stand-in for my father – whose time is out of joint, ten years late to arrive.

SM There’s a beautiful link between the architectural ruin of the airport and Oscar Niemeyer’s sports stadium, La Coupole, in Algiers, which you visit in Two Meetings and a Funeral. In that film, the Indian communist historian Vijay Prasad speaks of these large mid-20th-century public building projects as excessive and impossible to maintain. For me, they feel like the architectural equivalents of the political disappointments you examine.

NM You walk into some of these buildings and you inhabit a structure that signals vast vistas, where the individual is a speck on the horizon. They were designed during the cold war and in the flush of space exploration; you start thinking of existence within the long durée of the universe.

I think Vijay, coming from a direct approach to writing about histories of the Left, felt that the gigantic structure of La Coupole was wasteful. It was completed in 1975, at a moment in which Algeria’s oil revenues had been dramatically increasing, so they could afford it for a time – until oil prices fell and the money started running out. Like many of the OPEC [Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries] members that became rich in the 1970s, they didn’t plan for a future in which resources would run out.

SM I think such an expansive view of time is difficult to reconcile in the 21st century because we have such a different sense of the future. We feel so palpably the sense of living at the end of human existence.

NM Or, the humans walking into La Coupole can no longer visualize the utopian possibility – because we now live not so much under the shadow of nuclear war but of continuous, low-level war. The future we currently face is an overpopulated planet – in which we will go to war over water or food – unless a new Left project, against the silos of nation, race and religion, can be imagined in a different way.

SM Tripoli Cancelled is formally very different from your previous work. Is this the beginning of a new direction?

NM I can’t say yet, because I never have a clear plan. Some-thing I’m interested in moving towards is the cinema of slow time. Afsan’s Long Day is crammed with events; there’s very little quietness. With Last Man in Dhaka Central, I became interested in slowing down. It focuses on one figure, the Dutch journalist Peter Custers, who became embroiled in a Maoist uprising inside the Bangladesh Army that collapsed catastrophically in winter 1975. In trying to recall how he travelled from being a Johns Hopkins PhD student to a prisoner in a Dhaka jail, accused of conspiracy to overthrow the state, Peter talks for a long time. He speaks slowly, carefully, precisely.

My experience was that he would talk for many days and then, suddenly, he would say something crucial. For most of the film, you don’t see him: you hear his voice while the camera roams around his apartment. The only moment you see the interview is when I ask if he knew in advance that the 1975 Maoist uprising was going to happen. It’s a crucial question – after all, he was jailed by the Bangladesh government to force him to testify against his comrades. At that moment, the camera cuts to him. He hesitates and says: ‘It’s a little more complicated than that.’ And it’s not what he says – it’s his facial expression: the way his mouth opens to smile, and then decides not to, and his lips close again. You have to go through the previous 70 minutes of hearing him talk to pick up his speech cadences so, when something changes, you realize that the record is starting to skip.

Formally, I think Tripoli Cancelled comes closer to what I would like to do with slowing down time.

SM You have a strong sense of the formal qualities of montage in your archival films. The visual relationships are deliberately open and complex. There’s a sense of the slipperiness of history present in the image. Who have your key influences been in terms of working with the archive?

NM Let me narrow it down, for now, to the specific archive of the 1970s insurrectionary Left: Chris Marker, because of how his narration always kicked against the image record. Sharon Hayes’s Symbionese Liberation Army project [2003] as well as Sam Green and Bill Siegel’s The Weather Underground [2002]. Eric Baudelaire – our films about the Japanese Red Army [The Anabasis of May and Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi, and 27 Years without Images, 2011, and United Red Army] are in dialogue. And a film that I do not know how to process – Olivier Assayas’s Carlos [2010; about the Venezuelan-born Marxist revolutionary known as Carlos the Jackal]. Carlos has a frenetic reconstruction of the December 1975 attack on the OPEC oil meeting – a moment hinted at in passing in my script for Afsan’s Long Day. Assayas did a full-blown reconstruction, filling in all the missing scenes that are not in the newsreel. But I felt dissatisfied with the portrayal of Carlos as a testosterone-fuelled caricature – perhaps it’s not inaccurate, but it takes the sting away, as in other commercial films, about this moment of the radical Left.

SM How do you define ‘Left’ in the context of the 21st century?

NM Firstly, it’s a political project for the planetary redistribution of wealth from the hyper-rich to the majority, from the north to its former colonies. The Left’s project has been stuck in a defensive position of holding back the flood-gates of gangster capital; we need to start pushing hard to overthrow this system. That is why I spend so much time in the early 1970s, when there was still a possibility of a new economic order.

Naeem Mohaiemen works in New York, USA. In 2017, he had a solo show at Tensta Konsthall, Sweden, and presented two new commissions at documenta 14 in Athens, Greece, and Kassel, Germany. His exhibition ‘There Is No Last Man’ is on view until 11 March at MoMA PS1, New York.

Main image: Tripoli Cancelled, 2017, film still. Courtesy: the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata