The Discontinuous History of Claudia Pagès’s ‘Typo-Topo-Time Aljibe’

The artist’s new installation at SculptureCenter is a strained metaphor for colonization, gender binaries and time itself

The artist’s new installation at SculptureCenter is a strained metaphor for colonization, gender binaries and time itself

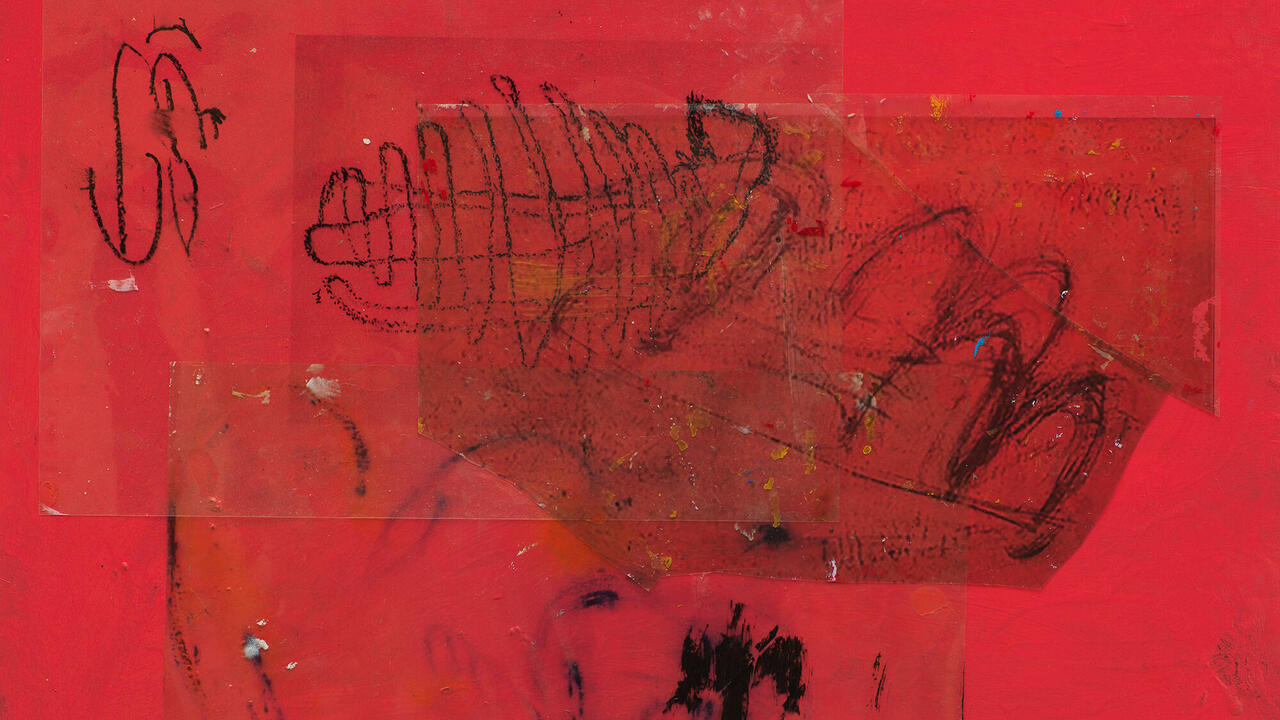

In her new video installation at SculptureCenter, Typo-Topo-Time Aljibe (2024), Claudia Pagès spelunks in an 11th century Moorish aljibe (cistern) in the Spanish town of Xàtiva. She also dips into history. Built by Islamic conquerors to collect rainwater, the cistern has also accumulated centuries of graffiti – like that from men named Miguel and Manuel, who outlined their signatures with cartoonish penises. The work is a palimpsest, too. The texts and symbols etched into the aljibe’s walls appear on screen traced with digital scribbles. The markings are layered, and so are the voices of the three people trying to interpret them, who speak in English, Spanish and Catalan. One gives the diver instructions like: ‘Go in the water. Wear goggles.’ Another waxes philosophical, at one point inspired to ‘erase the duals’, such as gender binaries, by the tall, uneven stairs.

There’s plenty to unpack here, at the nexus of Islamic and Christian empires, Africa and Europe, then and now. For instance: in 1056, while the Iberian Peninsula was under Muslim rule, Xàtiva became the first European town to manufacture paper using techniques imported via the Silk Road; water, such as that collected in the aljibe, is essential for paper-making; and the graffitied walls of the cistern are like the pages in a book. The video is shot from the perspective of an explorer paddling through a couple of metres of water, but it treats this aljibe as the reservoir of any and all meaning, full stop. It attempts to make ‘this one cool place’ a strained metaphor for colonization, gender binaries (and the lack thereof) and, especially, for time itself. ‘The torch’ – a headlamp or flashlight beam – doesn’t just illuminate the shadowy space, one of the narrators tells us, it ‘frames the visible’.

You get the sense that the piece’s internal logic isn’t meant to stand up, exactly, but to dissolve, seasoning an already deeply worked palimpsest and committing history to the wet tomb of impenetrability. The narrators identify some of the texts as 16th-century contracts – but for what? Was it common to draw up binding documents on the walls of the local cistern? It must not be important to know. Pagès presents the cistern’s confounding space and time as an antidote to ‘settler time’, a straight arrow of attack or erstwhile progress. So, the video loops – but the video is also linear, marked not just by the (excellent, clever) credits superimposed on a column but by the diver entering and exiting the water. The narrators often analyze signs of the gender binary in the graffiti: ‘Water is intuition, the feminine, but the first mark underwater is a penis.’ Except this is simply the first mark we see, a function of the diver’s scenography and not the essentially neutral simultaneous time of the aljibe.

Yet, this impulse to square the video’s circle feels important, and human. Pounding techno music grows tinny and distant when the camera submerges, seeming to echo through the arched masonry like the aura of some timeless postindustrial or postcolonial rave. I imagine the space drained of rainwater, filled with sweating bodies. Shaped to emulate an undulating wave or an open book, the LED screen recalls the theory that the Palaeolithic artists who painted the Lascaux caves used rippling rocks to suggest motion. The work rewards trancelike attention. At SculptureCenter, it is installed not in a padded theatre but in a hard, reverberant gallery. The light and sound bouncing off the concrete floor add to the watery sense of distortion and miscomprehension. It is, as one narrator says, an experience of human time as ‘discontinuous’.

Claudia Pagès’s Typo-Topo-Time Aljibe is on view at SculptureCenter, New York, until 19 February.

Main image:Claudia Pagès, Typo-Topo-Time Aljibe, 2024, installation view. Courtesy: the artist and SculptureCenter, New York; photograph: Charles Benton.