Close Listening

Phillip Sollmann’s latest composition pays homage to three distinct and unconventional instrument makers

Phillip Sollmann’s latest composition pays homage to three distinct and unconventional instrument makers

Earlier this month Berlin’s Volksbühne staged the debut of Monophonie, a composition by Berlin-based producer and composer Phillip Sollmann, who also goes by the name DJ Efdemin. Performed by the Cologne-based Ensemble Musikfabrik, Monophonie unites the unconventional acoustic sound devices of three musician-designer-scientists from the 19th and 20th centuries: Italian-born US furniture designer and sculptor Harry Bertoia (1915-78), US composer and instrument-maker Harry Partch (1901-74) and German physicist-polymath Herman von Helmholtz (1821-94). The resulting performance was like watching a team of linguists collectively excavating an ancient, esoteric musical language and transpose into a genre from an entirely separate, contemporary context: minimal techno.

Although they worked in different fields, Bertoia, Partch and Von Helmholtz each separately invented a body of experimental ‘instruments’. Within Sollmann’s conference of sonic eccentrics, it was the recreations of the sculpture-instrument hybrids of Harry Partch, originally made in the 1940s, which took centre stage.

Born in 1901 and a once train-hopping itinerant, Partch dropped out of composition school in California due to his non-compliance with standard Western 12-tone notation, known as ‘equal temperament’. After experimenting with alternate musical tonalities, Partch eventually came across Von Helmholtz’s Sensations of Tone (1863): a foundational musicological text, first translated into English in 1875, that explores the nature of acoustics, human perception of sound and systems of ‘pure intonation’. This system of tuning was the basis for the musical traditions of ancient Greek and classical Indian music, and was also demonstrated in Von Helmholtz’s own instrumental inventions. (In his performance Sollmann wielded the original Double Siren from Von Helmholtz's own workshop, sourced from the Institut für Physiologie in Berlin, amid the peaking dissonance of the other instruments by Bertoia and Partch.)

Due to the nature of the scales employed, to the untrained ear the sounds that come from Partch’s instruments resemble distant cousins of ‘harmonic partials’. Two adapted reed organs, Chromolodeon I and II, most clearly demonstrate this. Instead of the twelve keys (7 white 5 black) which form an octave on a typical keyboard, the notes between octaves are stretched out to span a total of 43 keys: allowing unfamiliar microtones to bloom. Because our ears are trained to understand the presence of equal separation of frequencies between octaves, the combination of these microtones can register as subtly non-harmonic: like cracks in a sidewalk of ‘major’ and ‘minor’ keys.

The evening began with the sound of a large metal gong, repeated over a few minutes of Monophonie as the ensemble members entered the stage one-by-one. Gradually, the first polyrhythms of the night arose from Partch’s Quadrangularis Reversum, a sort of multi-walled shrine to a xylophone. Made from bamboo, eucalyptus, and other hardwoods, the instrument’s multiple xylophone planes are positioned similar to a standard drum kit. As the stage slowly warmed up, the stage lights rose to reveal a metropolis of instruments of various dimensions all made from a variety of earthen materials: stained hardwoods, gourds, and glass. Throughout the evening, ones eyes were constantly exploring this crowded stage of instruments, following polyrhythms and synchronized percussive plonks as they were passed around the stage from instrument to instrument. When various percussive elements were combined, at times it sounded like subtly symphonic tribal house but that would soon fall back into a more abstract complexity of textures, warm with tones produced by mallets on Partch’s Cloud Chamber Bowls: bulbous glass forms resembling inverted margarita glasses hung from a wide rectangle threshold. With these polyrhythms came an oncoming haze of textures, bells and screeches played from Partch’s Harmonic Cannon – a horizontal string instrument resembling bleacher seating.

A younger contemporary of Partch, Bertoia wasn’t a composer but a designer of furniture who earned initial fame for his mid 20th century modern chair designs. After finding success in that field, he was able to devote himself to sculpture, resulting in a large body of kinetic and static objects. These interactive kinetic sculptures are various-sized vertical groupings of copper rods with cylindrical tops evenly spaced over the points of a grid, like the bristles of a toothbrush. They’re not so much ‘played’ as caressed by players’ hands. Each sonambient has a different resonant frequency, which is determined by the height, distance, and thickness between the vertical rods, like a mosh pit where all the participants feet are attached to the ground. When handled rough enough and all together, the sonombients emit a body-arresting metallic babble of thousands of minute forceful interactions of copper rods swaying back and forth against themselves. The effect is a visceral non-violent storm of noise pixels, like a group of negatively-charged electrons revolving around a swaying nucleus.

When a member of the ensemble would move one it was more as if they were starting a quarrel with the instrument rather than playing it. Shouting back with a jangly resonance, as it lost momentum the separate tones became more audible and spaced out until the interactions between the rods cooled down, producing sounds resembling delicate chimes. One of the joys of the performance was witnessing the interaction of the sonic quality of these sonambients against the limits of the array of Partch’s instruments, introduced in moments where the rhythmic energy started to feel exhausted. This kind of strategic placing of noise relates directly to Sollmann’s craft, not only in the production of techno tracks, but also in negotiating the problem of keeping a dance floor energized over the course of a four-hour long DJ set.

Perhaps the most surprising instrument wasn’t one from Partch’s catalogue, but a sort of external plugin-motorized apparatus stuck to a microphone stand spinning and whipping a metal wire across one string on a section of Partch’s Surrogate Kithara (a two tiered horizontal string instrument). The sound produced was a high-rpm single-note pluck. It was left to run while percussive elements fluidly crossed over, interchanged with other types of hard, resonant noises. This interchanging of ideas made sense in relation to the switching between settings and patterns within drum machine programming while producing techno live or in the studio – most of the time, the pace of these rhythms sat between 122-135 bpm, the average pace of a contemporary dance floor. The presence of a sub bass was reserved for a few special moments where a player would strike Partch’s Marimba Eroica, an instrument made entirely of redwood where long wood planks sit above a cave style resonating hollow box creating a guttural analogue low frequency.

Although the presentation of Monophonie in many ways suggested the conventions of classical music, thus framing our judgement of an overall ‘composition’, no one could expect Sollmann to deliver a single musical composition that could top the ingenious modesty of Partch’s idiosyncratic instruments. Sollmann’s staging of Monophonie was not so much about raising the bar on Partch, Bertoia or Von Helmholtz’s designs, and more about creating synapses between various histories of isolated ingenuity.

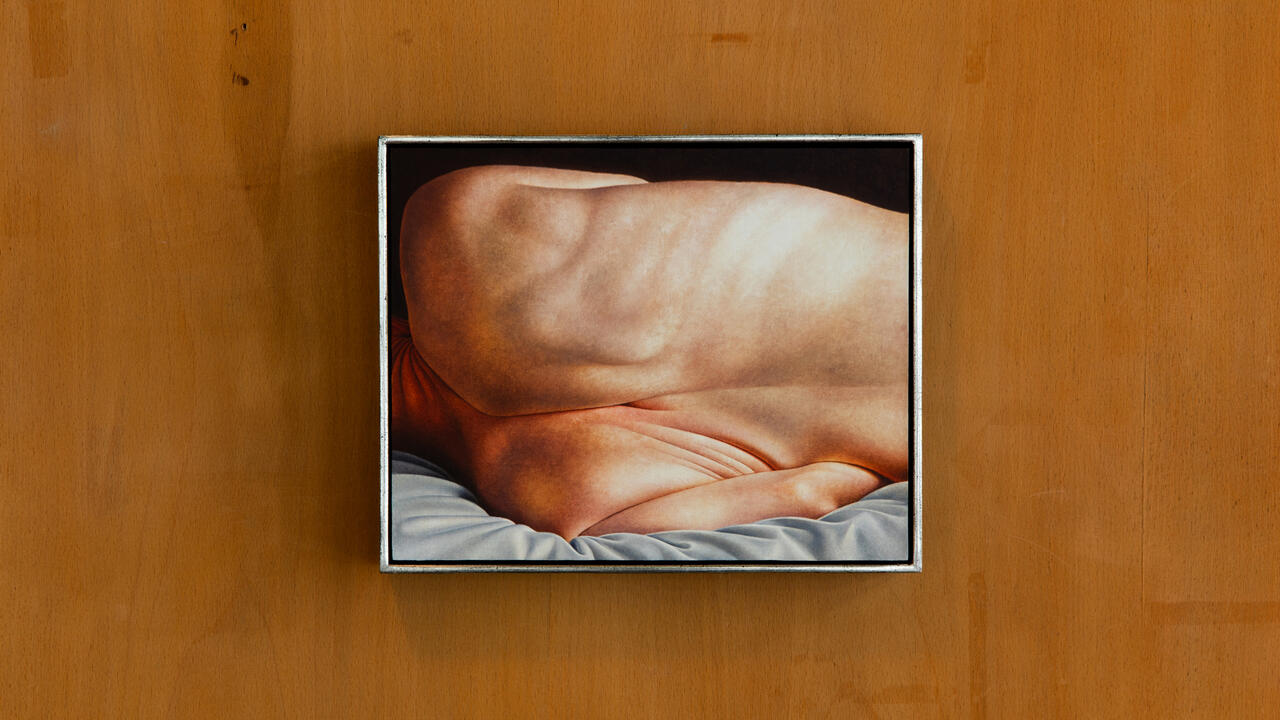

On 2 May 2017, Phillip Sollmann and Konrad Sprenger will debut a concert at the Kestnergesellschaft, Hannover, for Annette Kelm’s exhibition, ‘Leaves’ (11 March – 7 May 2017).

Main image: Annette Kelm, Sirene (detail), 2017. Courtesy: the artist, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; Herald St, London; König Galerie, Berlin