The Deadly Doris

With the reissue of their eponymous debut album, revisiting the career of legendary Berlin art project / punk band Die Tödliche Doris

With the reissue of their eponymous debut album, revisiting the career of legendary Berlin art project / punk band Die Tödliche Doris

As the 1970s drew towards its close, The Stranglers sang ‘No More Heroes’ (1977). Across Europe, in a still-divided Germany, Wolfgang Müller and Nikolaus Utermöhlen were not impressed. ‘It’s wonderful music,’ Müller admits when we speak over the phone recently. ‘But on the other hand, I thought, no more heroes, huh? The next are already waiting. The new heroes are on their way.’

Enrolling at art school in Berlin in 1980, Müller and Utermöhlen could see that the same punk movement that promised an end to all the heroes and ‘Shakesperoes’ was already producing icons and idols of its own. But the problem, they felt, with the likes of Sid Vicious was that they were too one-dimensional, scarcely more than the image of a leather jacket and a sneer. ‘So why not make a band constructing a whole character?’ they wondered. They set out to make ‘13 songs as different as possible – because as a character you are not everything at the same time.’

‘A normal pop star makes sentimental, melancholic music,’ Müller continues, ‘so that person gets an image. But [we set out] not to construct an image, but a whole personality. So you make a very funny, childish song; then a very depressive song; and a rough song afterwards. And you put these 13 things together in a way that nothing is left over afterwards.’

They called their invention The Deadly Doris – Die Tödliche Doris – and their eponymous debut album is about to be reissued on Superior Viaduct's new sub-label États-Unis, with nothing left over afterwards.

From the very beginning, Die Tödliche Doris was as much an art project as a rock band. Literally so, in fact, since Müller handed the album in to his tutor at college as a submission to a class assignment. ‘In the moment we began to study, we started the band. It was really the same time,’ Müller tells me. ‘The professor said, oh I didn’t see you [in class], what have you done? You have made a record cover?’

‘Yes,’ Müller replied. ‘I also made the music.’

How did your teacher respond to that?

‘Well, he was a bit shocked. But then he said, oh I heard you on the radio once. So then he was very proud. He thought we were ambitious. Maybe. I don’t know if he even heard the music.’

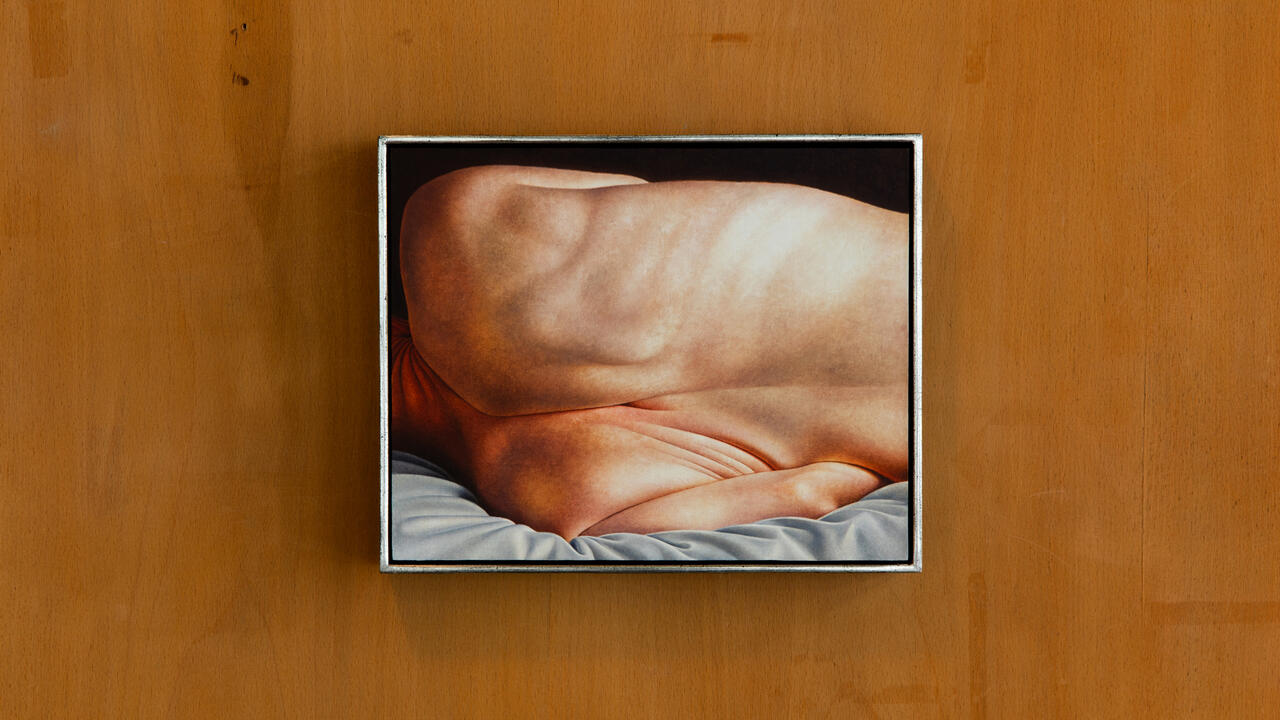

It is possible that what so alarmed the professor was not so much the idea of his pupils forming a band, but the sleeve of the record they presented to him. Beneath uneven type, hopelessly kerned and trailing off at the end, was a badly-lit and rather tawdry photograph of a young woman standing in stockings and suspenders before a black curtain, a small decorated Christmas tree and a spinning jenny by her sides. ‘It’s so bad!’ Müller exclaims gleefully. ‘It’s difficult to make a really bad design that people will think, oh my god, that is really, really bad. I studied graphic design. And the graphic design is a disaster.’

But the awfulness of the record’s appearance was part of a very deliberate strategy, summed up in the name lent by Müller to a music festival and subsequent manifesto: ‘Genialer Dilletanten’ [sic]. ‘Afterwards, there were a lot of myths,’ Müller says of the September 1981 festival at Berlin’s big top venue, the Tempodrom. ‘Mabel Ascheneller, the manager for Nina Hagen, said, we have one day where there is nothing happening, if you want to do something.’ With little time to pull the event together, pretty soon ‘everybody was talking with everybody.’ The eventual line-up would feature not just punk groups like Einstürzende Neubauten, Christiane F., and Gudrun Gut, but also future stars of the city’s techno scene, Dr Motte, Mark Reeder, and WestBam, as well as several people who apparently only got into music that very day. ‘People were making music on stage who had never performed before,’ Müller recalls. ‘Imagine: more than a thousand people go to a concert and nobody knows what will happen!’

The title – and its deliberate misspelling – was the work of Müller himself. ‘Ingenious dilettantes’, Müller explains, is a phrase ‘that bites itself’ – a contradiction in terms. ‘The two ideas are confronting each other so something could happen, because everybody is an amateur.’ The mainstream German music scene of the time was dominated by the sclerotic professionalism of bloated rock groups imitating worshipfully the virtuosic chops of groups from Britain and America. ‘We hate this kind of professional, imitated music,’ Müller spits. ‘They wanted to become traditional rock stars!’ Die Tödliche Doris were anything but.

For their performance at the Geniale Dilletanten festival, the trio (Müller, Utermöhlen, and drummer Dagmar Dimitroff) came on stage covered in fake fur and glittery face-paint, proceeding to play the violin with a fistful of feathers and bass guitar with a drumstick. For a concert at Martin Kippenberger’s SO36 venue in Kreuzberg, they had three strangers with no knowledge of their music take their place onstage, instructed to make any sound they like so long as they included a set of three texts prepared by the group. Invited onto the WDR TV show Rockpalast, they began by setting fire to the microphone before taking turns to perform maladroit solos on violin and accordion as it sizzled and crackled until, finally, the mic melted and dropped off its stand, leaving the final fifteen seconds of the performance to play out in total silence.

When they were not making music, Die Tödliche Doris made Super-8 films, like the ten minute short, Das Leben des Sid Vicious (The Life of Sid Vicious, 1981), with a two year-old boy in spiked hair and a swastika T-shirt playing the title role. Or they invented ‘meta-punk’ fashion items like the Woodpecker Shoe (made out of gristle, mould, bones, and animal tissue) or the Ornamental Dental Brace adorned with gemstones (‘It hurts and looks cool!’ the promotional material promised). They contributed to Harald Szeemann’s landmark 1983 exhibition ‘Der Hang zu Gesamtkunstwerk’ at the Kunsthaus Zürich and were invited to play at Documenta 7 (they refused, demanding more money and space in the programme, only relenting when their demands were met for Documenta 8, five years later).

But at the end of 1982, the group were faced with a problem. As Müller put it to me over the phone, ‘if you make one record with 13 characters, what can you do afterwards?’ The solution finally arrived one day in a Berlin toy shop. ‘I found these tiny records,’ he recalls, ‘for babies.’ Chöre & Soli arrived as a suite of 16 a cappella numbers spread over eight four-inch ‘miniphon’ records, designed to be played on a dolls house turntable. Next up, the group released two records, the confusingly titled third album Unser Debut (Our Debut, 1984) and the equally confounding fifth album, Sechs (Six, 1986), each bearing nine tracks with matching lengths. ‘You have to take both records,’ Müller explains, ‘put them on two record players, and you will see in your brain: the first invisible vinyl record will rise.’

After that, they had really hit a wall. After you’ve made an invisible record, Müller exclaims, ‘how can you make more?’ At a concert in the autumn of 1987, the band transubstantiated into a bottle of wine which the critic Masanori Akashi presented to the audience with his seal of approval. But if their career was relatively brief, never reaching quite the renown of their contemporaries Einstürzende Neubauten, Die Tödliche Doris clearly had a galvanising effect on the music scene of West Berlin in the early ’80s. They took punk’s anything goes promise to its nth degree, combining it in the process with the absurdist coprodelia of Müller’s hero, Dieter Roth.

For a long time, the project evidently continued to resonate with its members. Müller and Utermöhlen would still perform, from time to time, under the banner of ‘the school of Die Tödliche Doris’. Finally, in 1998, two years after Utermöhlen’s death, Müller collaborated with two German sign language interpreters, Dina Tabbert and Andrea Schulz, to create a stage version of the first Die Tödliche Doris album for the deaf, transforming both music and lyrics in a way that would convey the full range of its meanings to an unhearing audience.

Müller’s work since has ranged from ultrasonic recordings of bat calls (for an album called Bat, released the same year as Michael Jackson’s Bad) to a series of line drawings made with cobalt chloride ink that gradually disappeared (20 of which were purchased by Deutsche Bank). ‘I am still working with many of the same themes as Die Tödliche Doris,’ he tells me as we near the end of our conversation, ‘making the unseen seen and the unheard to be heard; playing with the hearable and unhearable, the visible and the invisible.’ Forty years after The Stranglers announced their demise, one last hero – a producer of invisible records and performer of inaudible music – has proved remarkably resilient.

Main image: Die Tödliche Doris (Dagmar Dimitroff, Nikolaus Utermöhlen, Wolfgang Müller) at the Geniale Dilletanten festival, held in Berlin's Tempodrom in 1981