Denise Ferreira da Silva on Refusal and Fugitivity

Black Brazilian contemporary artists confront the racial violence of the state

Black Brazilian contemporary artists confront the racial violence of the state

Following the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor by police in the US earlier this year, as well as the near-fatal shooting of Jacob Blake, fires have been burning across the globe to expose and protest the limits of critical discourse with regards to the failures of existing programmes for racial justice.

Though this has been an ongoing preoccupation in my work, it has taken a different aspect in recent years, as I encounter the works of Black Brazilian contemporary artists, who deploy Blackness to address racial violence through concealment and confrontation. Many, if not most, of these performers, poets and writers return Blackness to the scene of subjugation – where killing is always more than a possibility – not to reveal its truth but to render the depth of its refusal and fugitivity.

Fear for their lives – of the always already devious, dangerous Black body – is what police officers invariably claim when trying to justify their wholly unacceptable actions in these instances. A number of artists – including Mayara Amaral, Pêdra Costa, Lorran Dias, Juliana dos Santos, Tiago Gualberto, Laís Machado, Musa Michelle Mattiuzzi, Jota Mombaça, Jennyfer Nascimento, Paulo Nazareth, Iagor Peres, Ana Pi, Davi Pontes, Camilla Rocha Campos and Castiel Vitorino Brasileiro – have responded with works that unpack and expose the racial violence operating within discourses that criminalize the Black body and the state’s structures of protection and delivering justice.

Let me comment on how concealment functions as a method of confrontation in some of their works. By literally concealing her body, Mattiuzzi references symbolic violence in her performance Merci beaucoup, blanco! (2017). She does so by commenting on Brazil’s racial ideology of whitening. By covering her skin with white paint, Mattiuzzi uses her cis-female body as a canvas that returns the violence by expelling an expression of whiteness as wealth. Similarly, Nazareth’s Sound Installation (2014), exhibited as part of the Latin American Pavilion’s ‘Indigenous Voices’ presentation at the 56th Venice Biennale in 2015, undermines the anthropological expectations of cultural difference implied by the show’s title. Also confronting symbolic racial violence, Nazareth, who refuses to choose between his Indigenous and Black heritage, recorded a group of Guarani-Kaiowá children repeating phrases and words in Kaiwá and Portuguese – languages unfamiliar to many visitors. The installation also included a photograph of the Indigenous Brazilian rap group Brô MC and an autobiographical text that located the artist’s family history within the trajectory of violence that has marked Latin American and Caribbean nations since the conquest of the Americas in 1492. In works that directly confront the juridic authority underwriting enslavement and police shootings, both Nazareth and Mattiuzzi activate Blackness to refuse the symbolic violence of the anthropological discourse behind expectations of their practices as expressions of cultural and racial difference/identity.

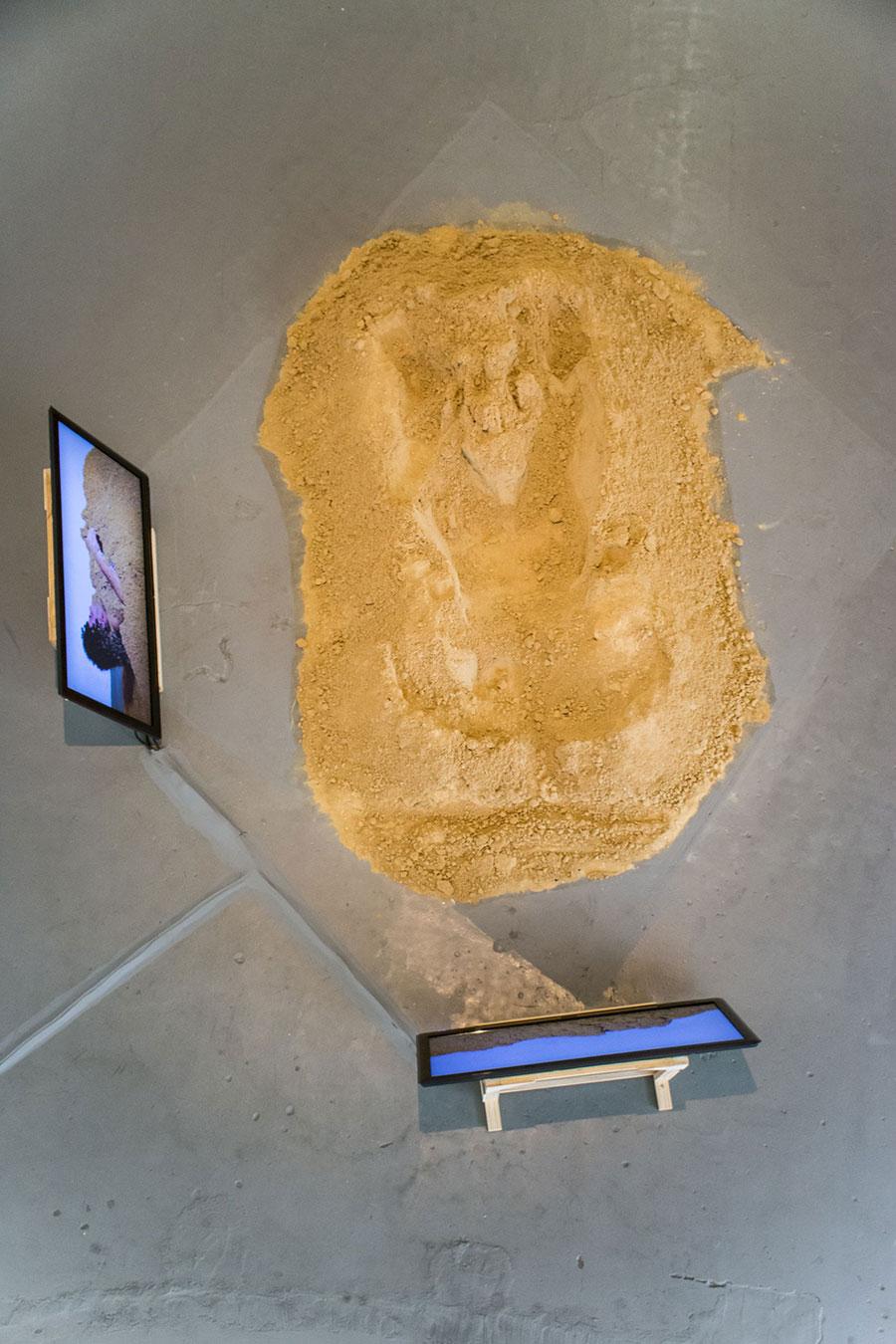

In Ali entre nós um invisível obliterante (There among Us an Obliterating Invisible, 2020), Recife-based artist Peres explores opacity as a refusal of symbolic and juridic authority. These sculpted skin pieces comment on Blackness’s capacity to embody what the artist – in a text accompanying the work – terms a movement from the ‘invisible to the unsayable’ and to evoke ‘other densities that permeate us’. Exactly this same movement is explored in Mombaça’s performance Soterramento (Burial, 2017), in which the artist’s semi-naked body is covered with sand and gravel while a list of names of those who have gone missing or who have been murdered by Brazilian police since 2013 is read out. In both works, Blackness’s ‘visibility’ serves as a mirror that reflects colonial and racial violence. By releasing the Black body from fear (the fear of being subjected and of being seen as a subject of violence), these artists expose and confront precisely that which is consistently occluded by the tools that produce the materials that inform critical discourse, whose failures seem to leave no other alternative than to set the world on fire.

Two works activate Blackness’s mirroring capacity when they camouflage this projected fear as seeming vulnerability. In Pontes’s Repertório N. 1 (2018), performed with Wallace Ferreira, the dancers’ bodies create sonic and optic effects that counter any attempt to project onto the Black male body the violence so frequently ascribed to it. Machado’s Mãe Pavorosa (Dreadful Mother, 2018) draws on what she terms ‘the positive meanings of violence’ – vehemence, exuberance, enthusiasm – to situate the female body at the intersection of racial and gender subjugation, identity and physicality. Reclaiming the Black body from fear, Pontes and Machado confront the deployment of a deadly authority that has no place in the contemporary political architecture, yet has never ceased to operate – as attested by the persistent state-perpetrated killings (documented or otherwise) of Black people.

With regards to the limits of critical discourse, which has motivated my own turn to art, what I find in these works is not so much an answer, a solution to this predicament, but a strategy one would expect to find in a practice that directly and unapologetically confronts colonial and racial violence. In activating the capacity of Blackness to return injury (haptically, sonically, optically) without acquiescing to racial violence and dwelling in fear, these artists put forth works that expose the failed promises of justice while underlining the uncertainty (opacity, vulnerability, precarity) that characterizes the mode of existence that announces a world to come.

Main image: Davi Pontes, Repertório N. 1, 2018. Courtesy: the artist; photograph: De Beija