Disobedient Curiosity

Ben Eastham delves into Goshka Macuga's exploration of art, power and history

Ben Eastham delves into Goshka Macuga's exploration of art, power and history

Read the Chinese translation here: ![]() disobedient_curiosity_frieze_179.pdf

disobedient_curiosity_frieze_179.pdf

There is no larger task than that of cataloguing a culture,’ asserts the narrator of Ben Marcus’s novel The Age of Wire and String (1995), who nonetheless sets forth ‘to present an array of documents settling within the chief concerns of the society, of any society, of the world.’ Writing from a ravaged, post-apocalyptic future, he faithfully documents for posterity such rituals as ‘Air days’ – ‘observed in the Western Worship Boxes, traditionally [...] the Half-Man Day following the first Sunday that a dog has suffocated the weather’ – and mysterious psychological disorders like snoring, a ‘language disturbance caused by accidental sleeping’, treated by ‘stuffing’ the patient with ‘cool air’. His behavioural study is divided into chapters categorizing its subjects according to the domains of knowledge (God, Animal, The Society), each of which concludes with a helpful glossary of terms.

This eccentric compulsion to taxonomize a culture is shared by the Polish-born, London-based artist Goshka Macuga. Where Marcus riffs to comic effect on the pseudo-scientific authority of the anthropologist’s report, Macuga plays on the ideological conventions of our museums – the institutions responsible for selecting and passing down the artefacts that shape our cultural identity. Her idiosyncratic study of the embedded hierarchies of value that determine what is worth preserving – and her attempts to formulate alternative systems – take the form of sculptural environments, tapestries, curatorial interventions and immersive installations that are politically charged, disrespectful of received ideas and frequently very funny.

To enter Macuga’s sprawling exhibition, ‘To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll’ at the Fondazione Prada in Milan, is to stumble upon an abandoned museum dedicated to a lost civilization. On stepping through a torn curtain, you are greeted by an uncannily lifelike humanoid who, perched on a raised dais, declaims snatches of the oratory that has shaped Western culture. Set amidst a spectacular congregation of monumental sculptures by Phyllida Barlow, Robert Breer, James Lee Byars, Ettore Colla, Lucio Fontana, Alberto Giacometti, Thomas Heatherwick, Eliseo Mattiacci and (in the form of the ripped fabric screen) Macuga herself, the robot regales his audience with a montage of epochal speeches by politicians, philosophers, playwrights and – in the case of the ‘attack ships on fire’ monologue delivered by Roy at the end of Blade Runner (1982) and HAL 9000’s dying rendition of the song ‘Daisy Bell (A Bicycle Made for Two)’ in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) – malevolent robots.

The show at Fondazione Prada is a meditation on beginnings and endings, set in a future in which humans no longer exist.

When I visited Macuga at her bright, book-lined and airy east London studio, she outlined the show as a meditation on beginnings and endings, set in an increasingly easy-to imagine future in which humans no longer exist. As with all of her work, the exhibition was preceded by a lengthy period of dizzyingly wide research: our conversation covered Renaissance studioli – rooms in houses and palaces dedicated to study or contemplation – as centres of knowledge-production; the impending moment at which artificial intelligence exceeds human control; posthumanism; the relationship between technology and creativity; and the ars memorativa, the set of mnemonic principles that allows us to organize, and thereby improve, our recall by applying architectural structures to our memory.

A second room at the Fondazione Prada, directly above the one in which the android holds forth, reinforces the impression of a space devoted to the imaginative juxtaposition of ideas, images and objects in the service of memory. Six long metal tables run in parallel lines along the space, across each of which is stretched a scroll of paper inscribed with dozens of arcane symbols, scientific formulae and scratchy ink sketches of canonical artworks by Marcel Duchamp, Francisco de Goya, Barbara Kruger, Egon Schiele, Leonardo da Vinci and others. Perched upon these curious ideograms, or presented in odd, custom-made glass showcases bolted to the side of the tables, are artworks and artefacts. These range from a 4,000 year-old Mesopotamian cylinder seal describing its civilization’s cosmogony, through bronzes by Giorgio de Chirico and Jacob Epstein to John Latham’s appropriately titled Art and Culture (1966–69), a regurgitation of Clement Greenberg’s book of the same name. The room can be seen to describe something like a (partial, subjective, speculative) pictorial commentary on the history of culture, commencing with the early stages of our evolution and running through to a chaotic human-less future. These are the cultural artefacts that the machines deem sufficiently freighted with significance to warrant conservation in perpetuity, fragments shored against humanity’s ruin.

While Macuga’s vast and multifarious networks of inference make it difficult to distinguish happy accident from intricately plotted correspondence, it seems appropriate that – at 60 metres – the full length of the scroll approximates that of the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, another pictorial history of a civilization’s rupture. The tapestry has been a feature of Macuga’s recent practice, stemming in part from her re-installation of a woven replica of Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) at the Whitechapel Gallery in 2009. The facsimile was loaned out by the United Nations, where it has been visible to all those who enter the Security Council since 1985 – with the infamous exception of the day on which US Secretary of State Colin Powell made the case for war against Iraq, when it was hidden away. At the Whitechapel, Macuga hung the tapestry as a backdrop for discussions (conducted at a round table) between anyone who took the time to reserve the space, on condition that they provided a written record of the meeting for an archive. The history of Guernica – from the painting’s exhibition at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris to its first visit to the Whitechapel in 1939 and the gallery’s unapologetic use of it as a propaganda tool (visitors to the exhibition could either pay the entrance fee or donate a set of boots to the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War) – helped to catalyze new discussions around a central theme of Macuga’s work: the relationship between art, power and history.

The experience encouraged Macuga to create a tapestry entitled The Nature of the Beast (2009), which presents a photo collage of figures posing in front of the replica Guernica in the style of The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s album cover (1967). The tapestry presents something akin to a Who’s Who of the contemporary east London art world, and it’s difficult to escape the nagging sense that this was an ambiguous homage to the networks of power that are so influential on the capital’s creative scene. For Daniel Birnbaum’s ‘Making Worlds’ exhibition at the 2009 Venice Biennale, Macuga composed another tapestry, Plus Ultra, which further illustrates the dense web of references and relations that underpin her practice. Curling across two columns, the work plays on a theory that the US dollar symbol derives from the Spanish coat of arms by counterpointing the mythical Pillars of Hercules with the Twin Towers; the central part of the image shows members of the G20 Summit perched on a cloud beside Emperor Charles V. Below these celestial representatives of power is a boat crowded with African migrants risking their lives to get to Europe. As Macuga’s London gallerist, Kate MacGarry, pointed out to me, in many ways Plus Ultra anticipates the current refugee crisis – and does so via an installation in the naval arsenal of a European city-state founded on sea power.

Macuga's vast networks of inference make it difficult to distinguish happy accident from intricately plotted correspondence.

That Macuga is unafraid of the politics of site-specificity was equally apparent in her two-part work, Of what is, that it is; of what is not, that it is not, for dOCUMENTA (13) in 2012. Originally commissioned for simultaneous exhibitions in Kassel and Kabul, the black and white tapestries depict a crowd in front of Darul Aman Palace in Afghanistan and protesters outside the Orangerie in Kassel. In a text published to accompany the work, Macuga presented the two tapestries as complementary ‘half-truths’, a statement typical of her reluctance to recognize or reinforce stable readings of history (and compelled by the artist’s own conflicted feelings about staging the work in Kabul, subject to the ‘threatening presence of the military’ and the ‘segregation of international elites from ordinary citizens’).

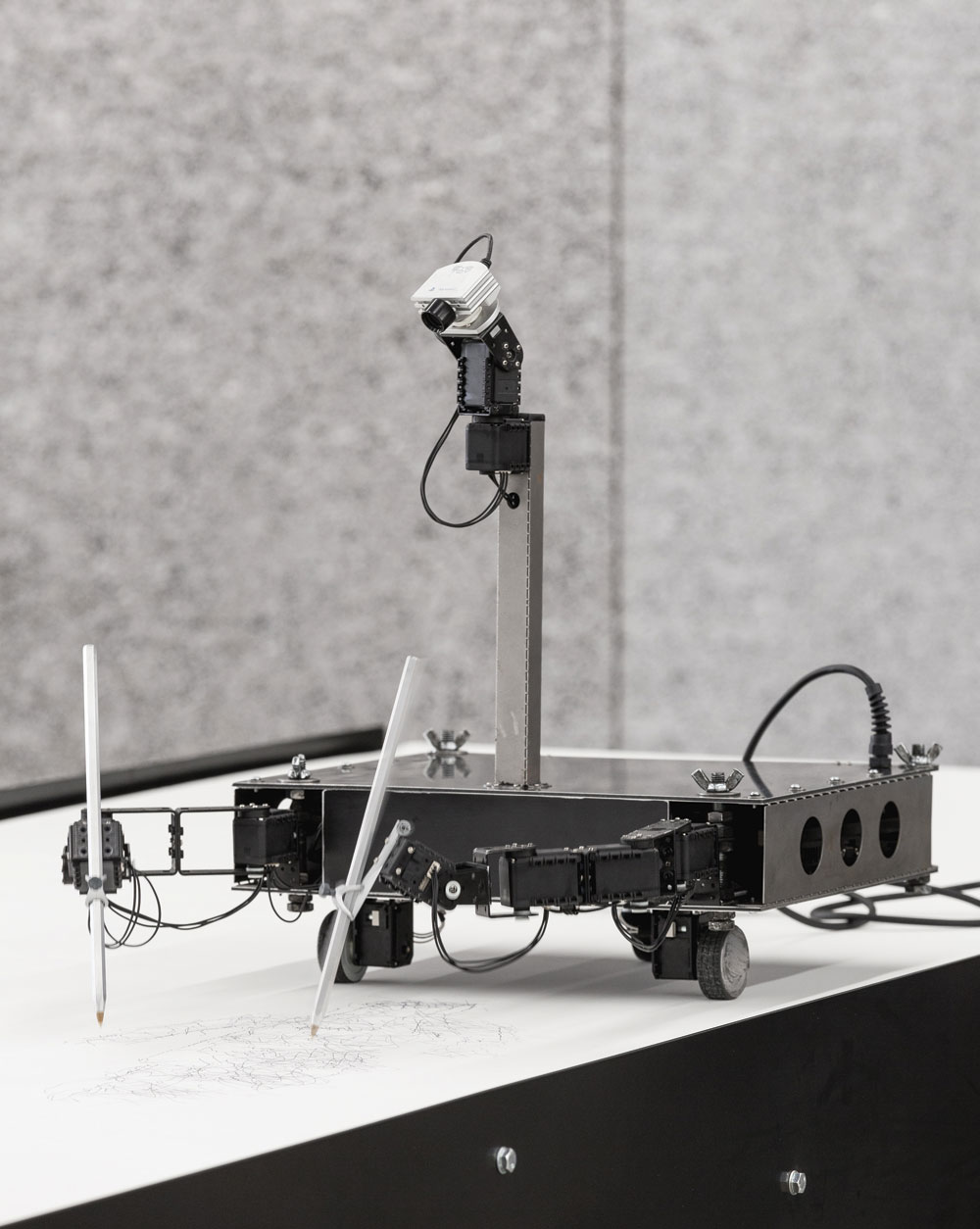

The Bayeux Tapestry was commissioned by William the Conqueror’s half-brother to commemorate the defeat of the Anglo-Saxons; at the Fondazione Prada it seems that humanity itself is the vanquished society, overrun by machines. On the final table of the upper room at the Prada, we discover the artists responsible for the drawings: two peculiar little wheeled robots that scoot up and down the paper surface. Their thin mechanical arms, with hinges corresponding to wrists and elbows, clutch two long pens with biro nibs. On a short neck is a swivelling camera-eye, which guides the jabbing, flicking gestures by which the arms inscribe marks upon the paper. Having reached this late point in the chronology, however, the robots seem to have gone haywire. Their previously neat renderings have degenerated into a chaotic, disordered scrawl, though whether this is a symptom of their dysfunction or a fair representation of humanity’s final, troubled phase is unclear.

These drawing machines are the creation of Patrick Tresset, and it is typical of Macuga’s approach that her exhibition should play host to another artist’s work. After organizing a series of shows at her own flat, Macuga’s first solo outing, ‘Cave’, at London’s Sali Gia in 1999, required visitors to step into a makeshift exhibition space constructed of crumpled brown paper. Featuring a selection of works by her circle of friends, the grotto might be understood as the first of the artist’s experiments in appropriating material and altering the circumstances of its display in order to challenge conventional responses: this was no longer a gallery, the sanctified space in which we commune with culture, but something akin to a smuggler’s hideout filled with treasure.

This fascination with suggesting new links between existing objects while engaging with the history of exhibition design was equally apparent in Macuga’s 2003 show at London’s Gasworks, for which she installed works by around 30 artists in a re-creation of the celebrated ‘picture room’ at Sir John Soane’s Museum. It was likewise evident in her ambitious exhibition for the 2006 Liverpool Biennial, ‘The Sleep of Ulro’. Working in collaboration with If-Untitled Architects, Macuga refitted the post-industrial interior of Greenland Street gallery with a labyrinthine complex of interlinking corridors, hidden rooms and vertiginous walkways inspired by the set designs for Robert Wiene’s expressionist proto-horror film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920). The effect elaborately undermined the possibility of a single route through the building, creating an immersive stage for the presentation of a bewildering array of objects. These items were commissioned or selected after a prolonged period of research into such arcane systems of knowledge as Renaissance notions about the tripartite division of the afterlife and the history of somnambulism. Such experiments in the creation of newly and internally coherent worlds are deeply engaged with the architecture of the exhibition space, a significant factor in Macuga’s retrospective at the New Museum in New York this summer. The show is the first time the artist has attempted to stitch together several different projects from recent years into a single exhibition.

Macuga's wildly allusive strategies question preconceptions about what is important and what is unimportant, what is true and what is false, and whether we should make such distinctions at all.

It could be said that Macuga’s medium is the exhibition itself, meaning that her practice is defined by her archival and choreographic engagement with the material; she is often cited as an exemplar of the artist-as-curator, or artist-as-archivist, or artist-as-curator-as-archivist. Macuga dismisses such categorizations, remaining adamant that she should be understood without qualification as an artist. Her approach differs in certain important respects from that of the curator: the conclusions she draws are frequently tendentious and always subjective, which could be considered an attempt to reassert the primacy of creative over scholarly approaches to the organization of material. When making decisions about what elements to include, she told me, she projects herself onto the exhibition, and cites the eccentric art historian and bibliophile Aby Warburg as an inspiration. It’s hard to imagine an institutional curator conceding that her decisions are based on intuition. Rather than make sense of things through the application of a rational schematic that reaffirms our existing prejudices, Macuga’s wildly allusive strategies question preconceptions about what is important and what is unimportant, what is true and what is false, and whether we should make such rigid categorical distinctions at all.

At the Fondazione Prada, the reliability of our robot narrator is called into question by his bizarre costume: transparent plastic blazer, flesh-coloured stockings and unmatched clogs, as well as a (at times surprising) selection of canonical texts. While its difficult to dispute that Shakespeare’s soliloquy on mortality in Hamlet (1603) has played a central part in shaping western culture, does the replicant Roy’s meditation on glittering c-beams in Blade Runner have an equivalent value? For all that he claims to be an impartial repository of human speech, is our guide guilty of a bias predicated on his likely sympathy for fellow fictional androids?

That Macuga might be wary of the narratives imposed upon history by those who write it is hardly surprising, given that she left her native Poland in 1989. When she returned to Warsaw in 2011, to present a major exhibition at the Zachęta National Gallery, she took as her theme the history of unofficial censorship at the institution. The same impulse – to use art history as a mimetic way of addressing broader political and social issues – can be seen in Macuga’s 2008 shows at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin and Tate Modern in London, in which she set forth to recover the legacies of two female artists, Lilly Reich and Eileen Agar respectively, who had not been afforded the same recognition as their male collaborators (and lovers). At the Fondazione Prada, one extraordinary installation running across three large rooms features 72 bronze heads of civilization’s great thinkers, connected by long metal shafts. They are arranged to resemble molecular structures and divided into discrete networks of influence according to the sphere of knowledge to which the figures belong. It’s at once celebratory and irreverent, like a deconstructed or defaced encyclopaedia.

Macuga opposes the presumption that whichever political, religious or scientific perspective is currently in vogue can ever offer us access to the whole truth about history and society. Her work upsets dogmatic thinking, preferring to reject palatable or convenient explanations in favour of a radical and disobedient curiosity. The truth, she reminds us, is forever in question.

Goshka Macuga lives in London, UK. Her solo show at the Fondazione Prada, Milan, Italy, ‘To the Son of Man Who Ate the Scroll’, runs until 19 June and her exhibition at the New Museum, New York, USA, ‘Time as Fabric’, runs 4 May until 26 June.