Doing the Splits

Blast Theory, Forced Entertainment and Slavs and Tatars: collectives fusing theatre, art, performance and politics to create interactive experiences

Blast Theory, Forced Entertainment and Slavs and Tatars: collectives fusing theatre, art, performance and politics to create interactive experiences

Blast Theory is a three-person collective based in Brighton on the UK’s south coast. Since forming in 1991, they have spun together artistic and scientific concerns into an extraordinary practice comprising site-specific research projects that turn the place of presentation into a space for role play. The entwinement of these fields in their work is visibly technical, linking audiences and performers through new media and often morphing one constituency into the other by using networked and locational devices to drive narratives. It is also implicitly political – the collective creates interactive, issue-driven performances that invite us to make ethical decisions about how we engage with, or interpret, the scenarios proposed. In the manner of expanded theatre, their works are part fact, part fiction and partially present: narrative microcosms that are then played out within the ‘real world’, sometimes to camera.

This heady mix of live art and performance writing methods, with simulation strategies more familiar to computer gaming, is one of the more radical strands of the booming experience economy. It is an approach to interactive art derived from anti-theatre traditions, which focus on encouraging the agency of audiences against the passive spectatorship set up by the proscenium stage. Blast Theory’s now infamous Kidnap (1998) is a complicated project about consent with a simple, yet shocking, premise: members of the public paid £10 to enter a lottery in which the prize was to be kidnapped, an experience that would be live-streamed and documented for an eventual 30-minute film. This notion of complicit participation remains central to their work. For their controversial collaboration with Hydrocracker, Operation Black Antler (2016), people could apply to assume a fake identity in order to attend a protest meeting as undercover police officers. Moving through the event – and so through the storyline – as actors and protagonists, they responded to the kinds of situations targeted by the recently disgraced Special Demonstration Squad, covertly deployed by the Greater London Metropolitan Police Service since 1968.

Like another vanguard British performance group, Forced Entertainment, who received the coveted International Ibsen Award in September 2016, Blast Theory’s significance within the intermedia arts was reaffirmed later that year when they won the Nam June Paik Art Center Award. What they will present in their prize-winner’s solo exhibition, which opens in late November at the Center in Seoul, remains to be seen – or, rather, experienced. Given the frictionless adoption of digital technology in contemporary exhibition-making, plus the current vogue for dance and choreographic practice in the visual arts, the curatorial challenge that Blast Theory’s work might have posed two decades ago is now more logistical than conceptual. Staging what they do is, presumably, costly and complicated. But the difference between a traditional art-world approach and how Blast Theory work highlights another, more interesting contrast, given the added value of mystification and reification that art’s symbolic and economic capital depend on.

Blast Theory operate like a theatre company. They have Arts Council England National Portfolio Organisation status and a sustainability model geared toward the mixed economy – drawing variously on consultancy work, com-missions, touring fees, grants, donations and institutional patronage – offering different solutions in return for each type of investment. At a logistical level, Blast Theory adopts neither the squat-based countercultural model of General Idea nor the opaque, studio-based approach of Art & Language. For those predecessors, the form of collectivity they created was an artwork in itself and the kernel of everything else they produced. By contrast, Blast Theory’s organization is pragmatic and relatively transparent, committed yet tactical. It is becoming increasingly common for contemporary art collectives either to ditch the traditional mystique and adopt non-art organizational structures, or to remain within the art world and maintain them. Dutch design studio Metahaven operate as a visual communications agency, US collective Critical Art Ensemble as a tactical media lab, and London-based Assemble as an architecture firm, while – from Åbäke to DIS – there are a number of design collectives gaining visibility in exhibition and biennial programmes. For each of these groups, the organizational model and commitment to an industry beyond fine art is not simply a background structure: it is something they positively identify with and directly affects how they address their work to their audiences, as art or as non-art in the context of art. Like Blast Theory, they all have different product lines for a mixed economy of potential audiences and markets.

These collectives may or may not seek to intentionally challenge the historical division of the arts, but they all seem to be teasing these traditional segregations by performing their difference to fine art, consciously asserting their status as non-artists producing content for art events. And they do so with a productive intensity that chimes perfectly with contemporary art’s appetite for non-art practices. If the first gesture of all art collectives is to dispute the sovereignty of the artist-as-lone-genius, by employing a non-art organizational structure and positively identifying with it, whatever they do present as art will have the charm of modest rebellion that aesthetic impurity invokes. What new forms of re-applied art become possible if collectives confidently ignore the question of whether or not what they make, and how they make it, complies with traditional definitions of art?

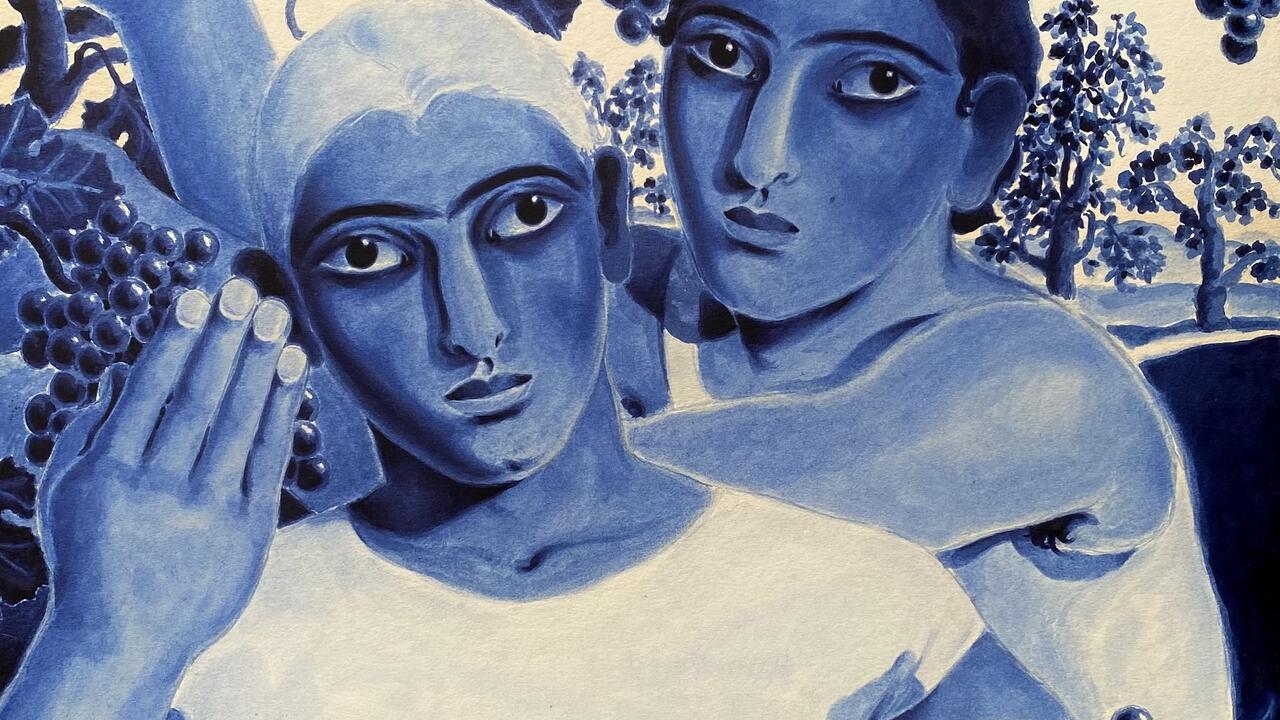

Few better examples have emerged in the last decade than the Berlin-based collective Slavs and Tatars, formed in 2006 by a designer-writer duo who produce installations, publications and lecture-performances. Their work demonstrates how seemingly contradictory argumentative positions may be re-interpreted as the poles of a spectrum, which can be represented without favouring one or the other. The consistency of their intentions was made clear in their first survey exhibition. ‘Mouth to Mouth’, which opened last November at Ujazdówski Castle in Warsaw, has since toured to Tehran, Istanbul and Vilnius and will open at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Belgrade this month before finishing its run in Dresden in early 2018. An elliptical wit runs throughout the show, one best captured by the figure of Molla Nasreddin – a Muslim cleric from the Middle Ages who was caricatured in an early-20th-century satirical Azeri periodical. The journal, Molla Nasraddin, whose title punned on the cleric’s name, itself became the subject of a book by Slavs and Tatars, Molla Nasreddin: The Magazine That Would’ve, Could’ve, Should’ve. A 2012 fibreglass sculpture, Molla Nasreddin the Antimodern – of a donkey walking one way with its rider, the Sufi wise-man-cum-fool, facing the other way – wobbles on its spring-mount. This functioning playground see-saw has an over-wide platform that fills the entranceway to the opening gallery of Ujazdówski Castle, inviting us to climb into the saddle and ride with Nasreddin. What would’ve, could’ve, should’ve been a radical movement – bridging thesis and antithesis like Walter Benjamin’s fabled angel of history – goes nowhere, stuck in the literal ‘now’ of the contemporary moment.

In the lecture-performance Al-Isnad or Chains We Can Believe In (2013), restaged on the closing weekend of the artists’ Warsaw show, Slavs and Tatars analogize their collective mission to the metaphysical equivalent of a gymnast doing the splits: one body pointing in two directions simultaneously – a form of thought that traverses a contradiction and so refuses a divisive split – the leggy figure of a spectrum. This is the method they apply across the questions and histories of a vast and turbulent territory, from the Berlin Wall to the Great Wall of China. The push and pull of competing ideologies (Sufism and communism), iconographies (sacred and profane) and functionalities (useful and useless) drawn from Eurasian traditions are condensed into polemical statements or objects, each one the conceptual equivalent of that hypothetical gymnast’s body. Their ‘Triangulations’ (2011) series of sculptures is a good example. Each iteration comprises a trio of short, floor-standing, cast-concrete triangles with inset texts that convey a double negative: ‘NOT MOSCOW NOT MECCA’, ‘NOT BERLIN NOT BUKHARA’, ‘NOT JUAN LES PINS NOT JERUSALEM’. These are place names, but not exclusively. Their ‘not-not’ logic concretized in the form of faux-commemorative paradoxes, they sit there, lowly, like road signs that point in a loop.

The six groups of work gathered in ‘Mouth to Mouth’ do not present Slavs and Tatars’s ‘not-not’ notion of the anti-modern as a tirade against the modern. Instead, a set of gestures and slogans protest against forgetting the past and rejecting local traditions, religions and the non-Western. The collective describe themselves as ‘a faction of polemics and intimacies’, offering clever propaganda against the Orientalist notion of the non-Western as necessarily non-modern. Their approach is mirrored in the show’s stagecraft – stylish rather than speculative – which may be a practical necessity for a six-venue tour but nonetheless feels a little overdetermined. From the galleries to the accompanying guide booklet, everything is eloquent yet explanatory, which poses a problem if we are seeking space to read the work differently. Like several of the other collectives mentioned here, Slavs and Tatars’s intelligence and consistency is impressive and productive: motifs and mistranslations recur across this survey so coherently that all of the works register as tokens of one ongoing project.

Their project loosens up when, in their words, the ‘intimacies’ lead the ‘polemics’. The most open works in the show explicitly celebrate all things bodily and flawed, from oral traditions to body languages, from the bodies of letter-forms to the body politic of communities. Hamdami (2016) is a short looping video with a gently warped narration running over garishly typeset, multilingual subtitles intercut with illustrative pictures. Through post-production, it creates a shared field for speech, text and image in the service of storytelling rather than advertising; it pitches anecdotes rather than authority. The show’s title, ‘Mouth to Mouth’, is as much a metaphor about resuscitating the supposedly marginal histories of Eurasia as it is about enjoying immediate contact with the images, ideas and stories that keep such histories alive. Swinging Septum (2014) is a 1.5-metre-high wooden saloon door in the profile of a nose, a mnemonic for the nasal-sounding phonemes that were not transliterated between Arabic and Latin languages or Latin and Cyrillic script and so were marginalized during waves of imperialism that wrote then overwrote the language standards of Eurasia. Motifs such as noses, as well as aphorisms dotted everywhere, make for limitlessly malleable content. And the objects representing them as art appear to be elegantly designed, context-responsive adaptations of that content.

Tactical responses, project-based methods, conceptual design solutions and fundamentally social, anti-romantic organizational structures: as Slavs and Tatars show us, doing the splits is a feat of bridging divided parts rather than an act of splitting. Aesthetic purists might not like their remixing of art and non-art methods and structures, but the imaginative ambition of contemporary collectives is finally being recognized as, or at least in, art.

Main image: Critical Art Ensemble, Radiation Burn: A Temporary Monument to Public Safety, 2010, performance documentation. Courtesy: the artists