Duty Calls

Hito Steyerl’s Duty Free Art and A Field Guide to the Snowden Files

Hito Steyerl’s Duty Free Art and A Field Guide to the Snowden Files

In her 2007 film Lovely Andrea, Hito Steyerl searches through Tokyo’s pornographic archives for a bondage image made of her in 1987. A performer, Asagi Ageha, acts as an interpreter and updates her on the current state of the scene. At one point, Steyerl asks Asagi what she’s studying. She answers ‘web design’, and we cut to cartoon footage of Spiderman swinging through high-rise buildings, firing silk from his hands. There is already a connection between the ropes of bondage and who holds power in pornography, but Steyerl adds a broader context: at one point ‘BONDAGE IS WORK/WORK IS BONDAGE’ flashes up on the screen. ‘Web’, here, has become a metaphor for networks of relationships within societies, and within artworks.

The pun is one of Steyerl’s favourite devices, in both her essay films and lecture-performances. As the title of her 2013 film How Not to be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File hints, these constantly overlap in content and in form. Her new book, Duty Free Art: Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War (Verso, 2017) essentially collects the scripts of lecture-performances developed over the course of their repeated delivery at institutions all around the world, on technology, warfare and fascism as means of understanding the conditions in which art is made, bought, stored and discussed in ‘the tailspin that we’re living through today.’

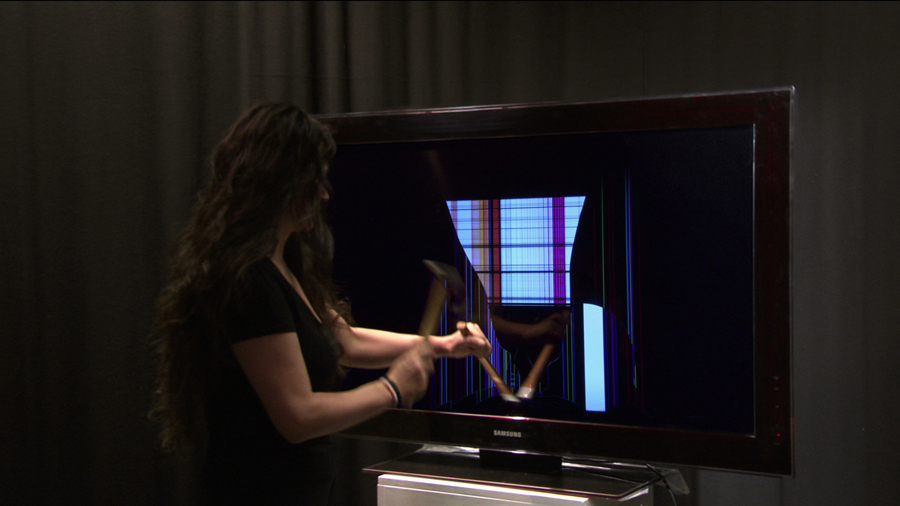

The second essay, ‘The Terror of Total Dasein: Economies of Presence in the Art Field’, suggests an update to conceptualist artist Goran Djordjevic’s 1979 idea for an artists’ strike. Instead of flying in to give a talk, the artist could be represented by a GIF on a laptop. Maybe it could be Steyerl’s 40-second film Strike (2010) – 14 seconds of a black and white title screen, followed by the artist walking up to a Samsung LCD TV, pretending to hit it with a hammer and chisel which prompts an image to emerge. Similar props could stand in for the audience, she suggests, or: ‘the much more elegant and dare I say standard solution for managing the economy of presence and making actual and real-life presence choices is to check your email or Twitter feed, while pretending to simultaneously listen to me.’

The chief formal difference about experiencing Steyerl’s ideas in book form, compared with on film or live, is that the pieces have spooling, etcerative footnotes which variously verify a claim with sources, or at one point – in the piece on scamming emails – highlight that an example is fictional. If there are still signs that these texts began as performances, it’s a good thing; they retain a directness of address and a performer’s sense of pace. Steyerl is not just consistently illuminating, but funny.

Probably the best example of this comes in the essay ‘Digital Debris’, with the yoking of Walter Benjamin’s description of Paul Klee’s 1920 painting Angelus Novus together with the ‘Spam’ sketch from Monty Python’s Flying Circus (1969–74). In the former, the ‘Angel of History’ is blown into the future, his face turned to the past, and the accumulating rubble-heap of history. In the latter, ‘spam – the canned food – slowly but decisively invades every item on the menu as well as the whole dialogue, until there is nothing left but spam, spam and spam’. Steyerl traces the use of the word on 1980s message boards ‘as an online activity bent on displacing something else by using verbal repetition’ up to the use of the technique to attempt to make money through bulk emailing. Digital technologies, she suggests, ‘provide additional possibilities for the creative wrecking of and degradation of almost anything.’

If Benjamin’s Angel of History had become somewhat of a cliché in the branches of philosophy connected to contemporary art, Steyerl reclaims it by embracing its ridiculousness: on the last line, she has us imagining it ordering Spam at Monty Python’s café.

The first half of the book’s title, Duty Free Art, is, of course, a pun, borrowed from an essay in which Steyerl brilliantly counterpoints two images reimagining the idea of public, national museums. The first is the storage of art in freeports, hoards bought to be kept in extraterritorial spaces as tax-free investment, never to be seen by the public. We’re introduced to them via a kind of dream-vision of places in which ‘time and space are smashed and rearranged into little pieces like in a freak particle accelerator, and the result is the cage without borders called contemporary art today.’ The second image is a municipal art gallery in Turkey which became a shelter for Yazidi refugees from Islamic State, just as it was holding an exhibition on genocide. The ‘duty’ in question here is that of purchasers paying tax on art, and, relatedly that of art itself to respond to the world around it; both may achieve a degree of what Steyerl terms ‘autonomy’ from these duties.

In 2013, Edward Snowden made a decision about where his duty lay and revealed thousands of unclassified documents, and throughout her book, Steyerl is repeatedly trying to come to critical terms with their meaning. Her theorization of the politics of visibility after the internet is a useful lens through which to read Magdalena Taube and Krystian Woznicki’s recent edited collection A Field Guide to the Snowden Files: Media, Art, Archives 2013-17 (Diamondpaper, 2017), and the accompanying exhibition, ‘Signals’, at Diamondpaper Studios, Berlin (12-26 September 2017). The book is structured in three parts – Media, Art, Archives – which respectively survey journalistic analyses of the files, appropriations by artists, and international archival initiatives. The artists include Laura Poitras, one of Snowden’s major collaborators, and Trevor Paglen, who features on Steyerl’s book cover. Paglen’s piece in the exhibition, NSA-Tapped Fiber Optic Cable Landing Site, Mastic Beach, New York, USA (2014) is a diptych comprising one image of an innocuous beach as seen by the general public, and another ‘NSA view’ including diagrams of ‘the routes and choke points of global telecommunications infrastructure.’

Similarly, in analogy to the respective sections of the web which are public-facing and ‘unaccessible and opaque to users’, the whole exhibition was divided into a ‘front end’ of art works and a ‘back end’ inviting visitor participation. Woznicki argues that, in relation to states and corporations harvesting data and conducting surveillance, ‘the general public is supposed to leave as many traces as possible and power should remain without any traces’. Snowden’s leaks extended the possibility of overturning this imbalance, but though the leaked material is available online, to view it from one’s own IP address is to open oneself up to the possibility of further surveillance. ‘The democratic organization of infrastructure for data and human traffic’, the editors declare, ‘becomes our vanishing point’, and, responding to Steyerl’s suggestion, the most immediate art-historical concern which emerges is that of an imbalance of power expressed through the politics of the gaze. Evan Light’s Snowden Archive-in-a-Box (2015) (SAIB), is a Raspberry Pi mini-computer fitted into a black suitcase – a skeuomorphic gesture to the spy-handler’s briefcases of a bygone era of espionage and defection – it lets users search the material securely: to disentangle themselves and see without being seen.

Probably the definitive moment of Steyerl’s book comes when ‘brutally summariz[ing] a lot of scholarly texts’, she defines her vision of a planet riven by civil war thus:

‘contemporary art is made possible by neoliberal capital plus the internet, biennials, art fairs, parallel pop-up histories, growing income inequality. Let’s add asymmetric warfare – as one of the reasons for the vast redistribution of wealth – real-estate speculation, tax evasion, money laundering, and deregulated financial markets to this list.’

There’s a neat switch when Steyerl draws in even those scholarly texts written free of any sense of political duty, or any conscious reference to the technological webs which now surround us. ‘Maybe’ Steyerl suggests, ‘the art history of the twentieth century can be understood as an anticipatory tutorial to help humans decode images made by machines, for machines.’

Main image: Hito Steyerl, How Not to Be Seen: A Fucking Didactic Educational .MOV File (detail), 2013 HD video still. Courtesy: the artist and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York