Elizabeth Peyton

RomaRomaRoma, Roma, Italy

RomaRomaRoma, Roma, Italy

Few galleries are blessed with a garden, and even fewer with their own fruit trees; RomaRomaRoma, however, has both. When I visited 'Elizabeth Peyton: Works on Paper', the gallery's backyard was lively with winter oranges, bobbing this way and that on stringy little boughs. Nearby, the grass was littered with gingery cigarette butts, imitating the fruits' citrus flush. Somehow, it wasn't hard to imagine that the people in Peyton's portraits were responsible for this mess. For a split second I pictured them huddled beneath the branches of the trees, smoking furiously, debating - like the narrator in T. S. Eliot's 'The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock' (1917) - whether they dared disturb the universe, or eat a peach.

Peyton's works depict people - her friends, her idols, the odd refugee from history. For her first show at RomaRomaRoma she focused mainly on her contemporaries. Only a drawing of Kurt Cobain, a figure who often appears in Peyton's art, pointed towards the past. Conjured up with sparse, pencil-crayoned lines, the Nirvana singer is shown jack-knifed over a desk, doodling in his diary, completely absorbed in a private moment. A lot of work went into his head - cadmium cross-hatching hems his eyes, his face is modelled with fine, deft strokes and his hair's a muddle of highlights. The objects that surround him, however, seem to be barely there at all. A can of Sprite fizzles out on the left, a packet of Marlboro is a smoky mirage, even his diary is ghostly - a single, gossamer sheet. The title of the piece is Kurt Writing (Newsweek) (2002). Perhaps it refers to the publication of Cobain's journals last year, a shabby bit of tomb-robbing that made public the suicide's pain. Peyton's image puts that pain back in Cobain's head. You might think you glimpse it in his features, or in the tight curl of his fist, but this is a flawed exercise in physiognomy, as meaningless as the patterns (produced, it seems, by some indolent madman) on the dead singer's walls.

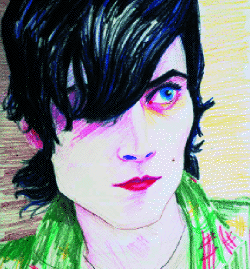

Peyton's portraits of Nick Relph are a different prospect. The young artist is represented as almost too pretty, an elfin creature who, in the watercolour Nick (2002), at least, appears to be fading fast, the victim of his own pale, consumptive loveliness. In her etching Nick in L.A. (2002) Relph is a lot tougher. Here he becomes a pursed-lipped, sneery professional - sexy but a little cold, like the boys in David Hockney's Illustrations for Fourteen Poems by C. P. Cavafy (1966). Peyton painted Hockney in 1997, working from a photo of the artist as a young man. In her hands he resembled a prettified Jarvis Cocker, the subject of one of her mid-1990s Brit Pop portraits. Looking back over Peyton's oeuvre, you begin to suspect that the she is, in a sense, a genealogist - that she's tracing a sensibility that's born in the gutter but gazes at the stars. Relph's work also mines this seam (his film Gentlemen, made with Oliver Payne this year, is as flâneurial as the prose of Victor Fournel), but in most of Peyton's images he's a rare flower rather than a productive force - a shy, passive man-child. In the monotype Nick in Red and Green (2002) Relph closes his eyes, his black hair licking his face, his shirt-sleeves lolling on a damp table. He could be any of those beautiful boys you see in big cities - sitting in cafés, measuring out their lives in coffee spoons, wondering 'what next?'

In the closing scenes of Curtis Hanson's film 8 Mile (2002) a barely fictionalized Eminem wins a Hip-hop face-off by listing, one by one, his own dorky inadequacies. This is rap's ultimate perfidy, but it frees him of the bullshit braggadocio that's been holding him back. Peyton's portrait Em (2002), an etching with aquatint, feels like the fall-out from this scene. The rapper's face knows nothing of its old anger. Here, it takes on the detached, critical aspect of late adolescence. Eminem is still tattooed, still be-muscled, but he also has a surprising moral authority, as though he's a good man gearing up for dark days ahead. In Alexander Pope's 'Essay on Criticism' (1711) the poet describes the English country garden as 'Nature to advantage dress'd'. It's possible to apply the term to Peyton's portraits, but I think they're more about becoming than about beautification. Here both Relph and Eminem feel, as Eliot wrote, 'the moment of [their] greatness flicker'. They are fruits yet to fall from the tree - gorgeous, yes, but also there to feed the future.