The Fraught Future of the Ethnographic Museum

With Macron poised to make changes to France's handling of ethnographic art, the quai Branly would do well to follow suit

With Macron poised to make changes to France's handling of ethnographic art, the quai Branly would do well to follow suit

A few days after I requested to speak with Sarah Ligner – the head of the Historic and Contemporary Globalization Heritage Unit at the musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in Paris – I received a telephone call from an unknown number.

On the other end was Thomas Aillagon, the communications director of the quai Branly, saying that Ligner – who curated the current exhibition, ‘Paintings from Afar’ – would not be available. When I asked why and whether anyone else at the quai Branly might be able to discuss the exhibition or French ethnographic museums at large, he replied ‘not at this time’. He then added that: ‘We simply oversee too much to make someone available.’ It was a bizarre claim given that the call came only a day after I’d sent along an overview of a few of my questions, some of which concerned the colonial nature of certain artworks in the current exhibition, and it had seemed to me that Ligner would soon be made available. But after I pressed Aillagon, the real motivation for Ligner's sudden unavailability made itself clear. ‘We will not be speaking about questions of post-colonialism at all,’ he said.

Later, Aillagon telephoned to clarify that what he meant was that he, personally, does not have ‘the technical background’ to discuss these issues. ‘It is not an institutional policy of the quai Branly to not answer these kinds of questions,’ he explained. The reason was simply because Ligner, who does have that expertise, was unavailable. And yet, after a fortnight of being told Ligner might be available but that she was ‘unavailable’ or ‘in Provence’ – even as her controversial exhibition was just opening at one of France’s most important museums – she has, at the time of publication, remained unable to answer any questions, even over email. The end result is that, official museum policy or not, questions of colonialism and post-colonialism at the quai Branly have gone unanswered.

It is, to put it mildly, not a good time for the quai Branly to be dodging fundamental questions about its exhibitions and mission. Contemporary ethnographic museums walk an increasingly thin tightrope: displaying what is often colonial plunder while neither defining it solely by its colonial origins (it’s still art) nor ignoring its provenance and the implications of power and colonialism therein. One solution to this seemingly impossible balancing act – which has always been a possibility but was brought only recently to the fore – is to repatriate much of the artwork, which would, if done on a large enough scale, necessarily lead to the closing of ethnographic museums.

While visiting Burkina Faso late last year, French president Emmanuel Macron declared that: ‘African heritage must be highlighted in Paris, but also in Dakar, in Lagos, in Cotonou. In the next five years, I want the conditions to be met for the temporary or permanent restitution of African heritage to Africa.’ (Later, on Twitter, the Elysée announced, ‘African heritage can no longer be the prisoner of European museums.’)

While many on the Left questioned the president's conviction and many on the Right criticized him for setting a dangerous precedent, Macron demonstrated his understanding that ethnographic museums are a threatened species and was, it seemed, putting French ones, like the quai Branly, on notice.

At its worst, wrote Caroline Ford, a historian at the University of California, Los Angeles, who specializes in colonialism, critics have called the quai Branly ‘nothing more than a project celebrating the "primitive" and thus reproducing the paternalistic exoticism of the West’s view of the non-European Other instead of challenging it.’

It's a damning claim – and it doesn't just apply to the quai Branly. Modern ethnographic museums, however, might still prove their continued relevance. In a talk given at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, Kavita Singh, an art historian at Jawaharlal Nehru University in Delhi, claimed that ethnographic museums, in order to stay pertinent, will ‘need to deliver greater degrees of contextualization and description for the objects that they exhibit.’

But what should that look like? Would a ‘contextualized collection’ in fact ‘replicate earlier ethnographic museum models?’ asks Ford. ‘Indeed, one might well ask in what terms and for whom the artefacts should be contextualized – primarily for the European viewer?’

The specialist museums of the late-19th century – mostly de-contextualized repositories of artefacts from non-European countries - are the progenitors of the modern ethnographic museum. Berlin's Museum of Ethnology, Paris's Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadéro (closed in 1935; the Musée de l’Homme is, effectively, its descendent), Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum, and Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology were founded as, essentially, cabinets of curiosities that, in turn, took their cues from 17th- and 18th-century ‘royal collections’, which themselves can now be found in English museums such as Oxford’s Ashmolean Museum or London’s British Museum.

Surely, this anachronistic style of decontextualized, ‘here, look at our colonial loot’-type of museum should not be the future of the modern ethnographic museum. But to more broadly contextualize African, Asian, and Oceanic works in a way aimed towards an explicitly European viewer – which also tends to mean the curator is European or, at least, a Europeanist (Ligner, a young Frenchwoman educated at Paris's National Heritage Institute and the École du Louvre, is both) – is to, at least in part, replay colonialism within an institutionalized setting.

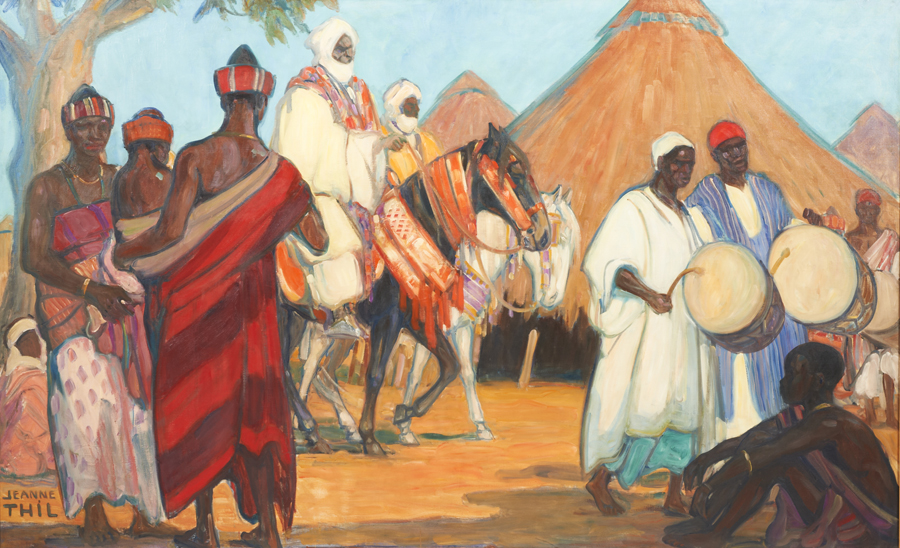

‘Paintings from Afar’, the current exhibition at the quai Branly, about which I’d hoped to speak with Ligner, attempts to illuminate the grey area between a decontextualized exoticizing of ‘distant lands’ and an admission of European social and artistic hegemony by presenting and then questioning the colonial lens. With over 200 works from the museum’s permanent collection, the exhibition showcases, among other works, George Catlin’s portraits of Native Americans, Emile Bernard’s scenes of quotidian life in Cairo and Paul Gauguin’s drawings of Tahiti.

The exhibition moves chronologically, showing how Europeans engaged with ‘the Orient’ in the late-19th century and what that engagement changed about European artistic life – the founding of Paul Leroy's French Orientalist Painters' Society, in Paris, for instance – while also pointing out the then-typical views of ‘exotic lands,’ through, for instance, the manifold artistic depictions of Paul et Virginie, Jacques-Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre's love story on the then-French-colonized island of Mauritius. The story – and the paintings about it that hang in the exhibition – depicts the colony as a place of Edenic serenity, even as its people were subjugated and the two young protagonists happily owned slaves.

‘Paintings from Afar,’ the museum's materials say, is about the initial ‘temptation of exoticism’ of the art and the attempt to find a ‘more realistic, ethnographic perspective that is mindful of the Other’. I visited the exhibition twice, and it’s clear that Ligner has indeed tried to show the how the Western gaze is applied to ‘the Other’; yet while the exhibition does well to present the colonial perspective it seems to forget to effectively subvert or intelligently critique it, with one room called 'Artists' Journeys and Circulation of the Occidental Model' that seems to praise the French artists who went to the colonies to teach fine arts and in doing so provided ‘non-occidental artists to represent themselves through the prism of European influence.’ Ligner has done well to provide lenses of both art and a broader sense of history to view the works, but the perspectives are nonetheless from mostly French – and a few American – artists and do little to subvert typical colonial views. At best, the exhibition only underlines them. (Ligner, it should be noted, is confined by what is in the museum’s collection.)

This attempt at merging socio-politically delicate art and a more responsible telling of history was the original intent of the quai Branly, with the important difference that many of the curators and researchers would have rigorously studied or perhaps have actually been from the countries and ethnic groups being depicted. This was, at least, the hope of Jacques Chirac, who was France's president when he officially established the museum in 1998. (It opened to the public in 2006, a year before he left office.) The anthropologist Maurice Godelier felt similarly, hoping it would become ‘a resolutely postcolonial museum, helping the public to step back and take a critical view of Western history’. What if, Godelier imagined, a museum could ‘combine two pleasures: that of art and that of knowledge?’

But, with the rise of multiculturalism in late-1990s France, the museum’s organisers decided to steer clear of individual identity politics entirely, cutting out indigenous populations and those being represented in the museum's curatorial decisions, according to Ford’s ‘Museums after Empire in Metropolitan and Overseas France,’ in The Journal of Modern History. Instead, the museum chose to use its ethnographic objects to promote a French republican universalism – the ‘tribal arts’ through French eyes.

The quai Branly could still return to Chirac and Godelier’s hopeful ideals and change the perspective of the museum so that the works of former colonies are viewed from a perspective other than that of the colonizer. What if Europe was not the ultimate focal point of history and art but rather just one point among many? The only way for the ethnographic museum to survive, as Singh also noted in her speech, is for ‘Enlightenment Europe ... to appear as an ethnic particular.’

This solution of maintaining the focus of the museum but changing the lens means the quai Branly would no longer be ‘ethnographic’ insofar as it concerns the people of non-European cultures as viewed by Europeans. Rather, it would become a museum that, run and curated by Europeans and non-Europeans alike, might explore non-European art through a variety of ethnic and demographic angles.

Given Macron's proposal to repatriate African artworks in France, many of which are in the quai Branly, it is hardly surprising that the leadership at the museum would perceive an on-the-record conversation about colonial art as undesirable, perhaps especially so given the current exhibition's attempt to show the history of a resolutely colonial perspective.

Stéphane Martin, the president of the quai Branly, has said: ‘Nowadays we cannot have an entire continent deprived of its history and artistic genius.’ This points to the quai Branly making a good start; and yet, even if Ligner was legitimately unavailable for two weeks during the beginning of a major and controversial exhibition she curated, the quai Branly must, in one forum or another, further address the underlying issues and implications of the modern ethnographic museum.

To merely present through the traditional European lens – and not actively critique – the role of colonialism, especially in an exhibition that claims to grapple with ‘colonial Europe’ and ‘colonial propaganda’ and within a museum that deals with colonial art is to act not just irresponsibly but foolishly as well. As Macron is poised to make serious changes to France's handling of ethnographic art, the quai Branly would do well to do the same. Its very existence might be at stake.

‘Paintings from afar’ runs at musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac until 28 October 2018.

Main image: Frédéric Regamey, Colonial Delegates and Mr. Jules Ferry – November 1892, 1892, oil on canvas, 106 x 95 cm. Courtesy: © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac; photograph: Claude Germain