Geoff Dyer Shows How Modern Culture Shaped Photography

The author’s latest book, See/Saw: Looking at Photographs, condenses over 100 years of history into selected moments

The author’s latest book, See/Saw: Looking at Photographs, condenses over 100 years of history into selected moments

In his introduction to The Ongoing Moment (2005), Geoff Dyer fulsomely admits he doesn’t own a camera, before cheerfully embarking upon a masterful essay comparing the great photographs of the American Century. As someone who has spent the last four years writing a novel about a dead photographer while knowing nothing about the technical aspects of the medium, I found this admission a massive morale boost. Dyer has the distinctive ability to be simultaneously incisive and agile with his subjects – he paces through timeless questions and judiciously selected moments effortlessly.

Years of meticulous looking and thinking are evident in Dyer’s latest book – See/Saw: Looking at Photographs (2021) – a taxonomy of 40 photographers and anthology of essays. Exploring work spanning from 1904 to 2014, Dyer condenses over 100 years of history around a loose chronology of carefully chosen photographs. He leads us from Eugène Atget’s haunted images of fin-de-siècle Paris and Alvin Langdon Coburn’s early-20th-century ‘daylight nocturnes’ of London and New York, to August Sander’s ‘People of the 20th Century’ (1927). But it is only when we reach Ilse Bing’s Greta Garbo (1932) that things begin to feel viscerally close to modern society as we currently understand it. The image of a half-torn poster of the actress hanging on a derelict hoarding in Paris during the Great Depression is, in Dyer’s words, ‘an advertisement for that eternal essence in a state of advanced deterioration’. In a society racked by plague and the threat of imminent climate collapse, we can relate to it all the better.

We don't encounter any grand historical moments in this overview: Robert Capa’s American Troops Landing on D-Day, Omaha Beach, Normandy Coast, France (1944) and Joe Rosenthal’s Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima (1945) are nowhere to be seen. Instead, we have Vivian Maier confronting us in her sensible suit (Self-portrait, 1953) and Peter Mitchell capturing a debonair scarecrow in a field somewhere after dark (Some Thing means Everything to Somebody, 1974–2015). We learn far more about ourselves for these choices. If Capa’s shots of drowning soldiers on French beaches were supposed to warn us of the irredeemable evil of violence, they have failed miserably, whereas the relentless interrogation conducted by Maier – of herself, of her subjects, of us – will never fail to give me the creeps.

Dyer insists upon the absence of narrative in photography: ‘There is no going beyond the moment because, in anything but the technical sense – one 250th of a second or whatever – the moment does not exist. Cameras provide the option of focusing on a distance given as infinity. The equivalent shutter speed would, I suppose, be eternity.’ This, I naively believe, is Dyer distinguishing the technicalities of the machine from the storyteller in him. Yet the very images he chooses have storytelling powers in themselves. The narrative of Fred Herzog’s Man with Bandage (1968) runs through every sinew of the forlorn man, from the cigarette dangling from off his fingertips to the bandage around his fist to the toilet paper covering his shaving scars. Beginning, middle and end are all there for anyone who cares to imagine them.

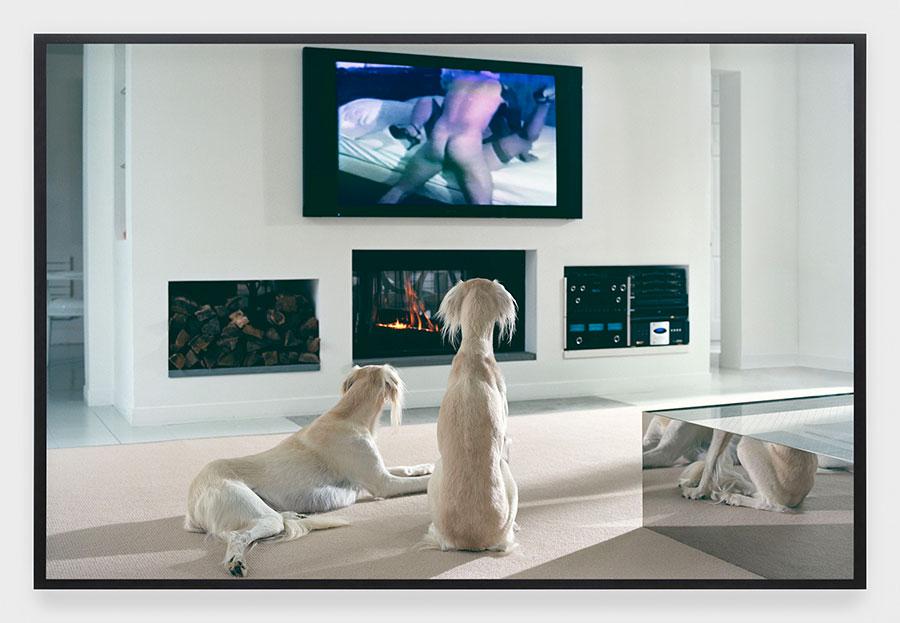

As we reach photographs from the 21st century, the human figure recedes, though that doesn’t take away the opportunity for self-reflection. Take Philip-Lorca diCorcia’s The Hamptons (2008) – two dogs transfixed by a porn film screened in a luxurious sitting room – or the vibrant rows of stacked shelves in a sparsely populated supermarket in Andreas Gursky’s 99 Cent (1999). Perhaps the most striking thing is that the tight arse and long legs in The Hamptons are there only via a screen, while the figures browsing Gursky’s shelves are eclipsed by the colours and the E numbers – a far cry from Maier’s relentless countenance. Has the spectacle superseded rigorous inquiry? Dyer might dig narrative in photography after all.

Perhaps the most satisfying choices in Dyer’s book are those photographers with a keen sense of place mangled by a precarious moment in time. Chris Dorley-Brown’s Sandringham Road & Kingsland Road, 15 June 2009, 10.42am–11.37am (2009) and Tom Hunter’s The After Party (from the series ‘Life and Death in Hackney’, 1999–2001) intimately capture ephemeral details from the changing fabric of society – something that has become almost a pastime in the age of camera phones. Both are severed snapshots: the broken sign of the venerable J. Hull & Co. tailor’s shop in Dorley-Brown’s photograph is overshadowed by an advertising hoarding for Evian spring water, while a gentleman strolling by in a cloth cap seemingly can’t quite get the knack of navigating a changing city. The knackered party-goer in Hunter’s snapshot seems afraid to get too comfortable on his single bed for fear he will be carted off along with it, back into the shadows to make way for the Olympic jamboree.

There may be no room for Capa in these pages, but there is still room for conflict. There is always room for conflict. In the 21st century, this means Gary Knight in Dyala, Baghdad, Finbarr O’Reilly in the Gaza Strip and Justin Sullivan in Ferguson, Missouri. The historical comparisons Dyer draws from these works might not cause the same jolt to the system experienced by the haunted observers; nevertheless, the details he isolates and opens leave us lurching into indefinite and profound territory, bereft of the excuse that we did not know what was going on before.

I only wish my own unfortunate photographer/muse Zbigniew Uglik, shot dead by the British army in Belfast in July 1970, had lived and worked long enough to develop the technical nous to make a final cut in Dyer’s book. Only someone with Dyer’s eye for detail could have been the judge of that. But we can’t have everything. As Dyer reminds us, photography, even the best of it, inherently limits an already limited version of reality. If there is an arc to this collection maybe it’s the closing of the American Century he so lovingly documented in The Ongoing Moment.

As it stands, we have only shards of negatives to pick from the darkroom floor as we await a coherent story of what comes next. As Dyer observes of Mitchell’s pictures: ‘If only there were a photograph of a crow perched on the shoulder of the thing designed to instil fear.’

Geoff Dyer, See/Saw: Looking at Photographs, 2021, is published by Canongate, London and Graywolf Press, Minneapolis.

Main image: Tom Hunter, The After Party, 2000, chromogenic colour print, 135 × 167 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Purdy Hicks Gallery, London