George Washington, Town Destroyer

It’s time to reckon with a US founding father who waged genocidal warfare against Indigenous nations

It’s time to reckon with a US founding father who waged genocidal warfare against Indigenous nations

The current dispute over monuments in the US is not new. In fact, it dates back at least to 9 July 1776 when, after a public reading of the Declaration of Independence, a group of Continental soldiers and New Yorkers, calling themselves the ‘Sons of Freedom’, pulled down the equestrian statue of King George III on Bowling Green. Like the statue of Christopher Columbus targeted in Boston last month, it was beheaded and the crown finials of its surrounding fence sawn off. The saw marks are still visible on the fence – scars as enduring as those that the American Revolution and its aftermath left on the Native nations of Turtle Island (North America).

In July 2020, Americans are once again divided, gathering in the streets and tearing down statues. Donald Trump recently condemned these actions in a speech delivered in front of his latest provocative backdrop, Mount Rushmore, in Lakota territory illegally seized by the US in the 1870s. Deeming attacks on statues ‘a merciless campaign to wipe out our history, defame our heroes, erase our values and indoctrinate our children’, Trump’s rhetoric echoes the description of Native people in the Declaration of Independence as ‘merciless Indian savages’. Ironically, his choice of words more aptly applies to the American campaigns against Indigenous nations, which erased our histories, demonized our heroes, scorned our values and acculturated our children in boarding schools.

Following the 2017 clashes at a white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Trump presciently observed: ‘So, this week it’s Robert E. Lee [...] I wonder, is it George Washington next week [...] Thomas Jefferson the week after [...] Where does it stop?’ The short answer is that it doesn’t stop until the US contends not only with its history of slavery but also its history of dispossession. Both Washington and Jefferson enslaved and waged war against Indigenous nations to dispossess them of their homelands.

As a Mohawk citizen of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy – the oldest living democracy in the Western Hemisphere – when I see statues of Washington, like the towering equestrian monument at the Virginia Capitol in Richmond, or the colossus in front of Federal Hall in New York, I see not only a founding father, but also a genocidal one.

The title by which Washington was known to Native nations, Hanödaga:yas or Town Destroyer, was one he inherited from his great-grandfather, John Washington, a slave-owning planter and colonel in the Virginia militia who, during Bacon’s Rebellion of 1676, had the chiefs of several tribes killed. His great-grandson lived up to the name of Town Destroyer in his treatment of Indigenous nations both during and after the Revolutionary War (1775–83). Wanting to remain neutral but forced to choose sides, some Haudenosaunee nations fought alongside the colonists during the war. Others, like the Mohawk, fought with their longstanding allies, the British.

In 1779, Washington launched a full-scale invasion of Iroquoia, our extensive homelands. In his orders to campaign leader Major General John Sullivan (after whom Sullivan Street in Manhattan is named), he wrote: ‘The immediate objects are the total destruction and devastation of their settlements and the capture of as many prisoners of every age and sex as possible. It will be essential to ruin their crops now in the ground and prevent their planting more.’

Town Destroyer’s armies burned and plundered 60 of our towns and hundreds of our farms, fields, orchards and livestock, forcing our people to evacuate. Hundreds perished of starvation, disease and exposure – a Haudenosaunee Trail of Tears.

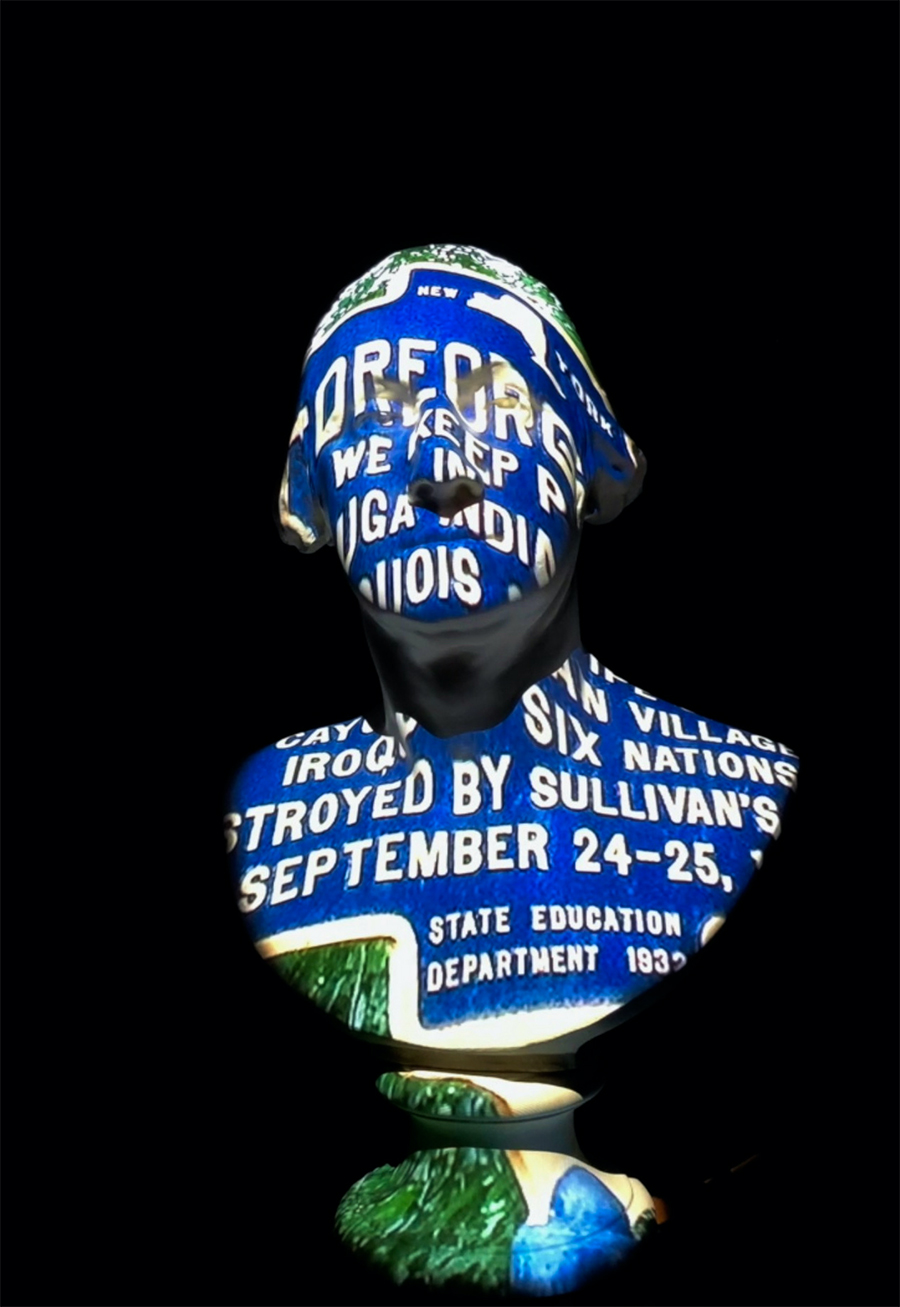

For my 2018 video installation Hanödaga:yas (Town Destroyer), I projected video referencing this scorched-earth campaign onto a replica portrait bust of Washington. In ‘Wolf Nation’, my 2019 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, I marked the 240th anniversary of Washington’s ruthless invasion with an augmented reality version of this work. Few visitors to the museum had ever heard of the Sullivan Campaign, or knew that most of New York state was our original homeland. Many expressed distress at the revelation. Scarcely considered or acknowledged, our catastrophic losses, like those of other Native nations, are treated as settled business, rather than unsettling travesties in need of redress.

White supremacy, grounded in the Doctrine of Discovery – the absurd claim by European Christians and their American descendants that they were more entitled to our lands than we were – was the rationale for dispossession. It is an ideology that has been so thoroughly internalized that it has never prompted a national reckoning. This devastating history has been papered over with myth, in a familiar national narrative established by writers such as James Fenimore Cooper, whose father, like Washington, was a successful speculator in Native land.

The time has come to even reconsider towering figures like Washington, honoured for their roles in founding the US, yet profoundly implicated in its colossal and, tragically, ongoing ethical and humanitarian failings.

Main Image: Washington Square Park Arc, 2020. Courtesy: JASON SZENES/EPA-EFE/Shutterstock