At MoMA, Georgia O’Keeffe Is a Half-Hearted Minimalist

By focussing on the artist’s serial drawings, the exhibition goes to great lengths to unburden O’Keeffe of her sensual associations

By focussing on the artist’s serial drawings, the exhibition goes to great lengths to unburden O’Keeffe of her sensual associations

At 96, Georgia O’Keeffe – supported by her young companion, Juan Hamilton – came to New York for the 1983 Alfred Stieglitz retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Having overseen Hamilton’s curation, O’Keeffe also authorised the inclusion of her dead husband’s famous portraits of herself, or of the self that she and those images co-constructed: a few years earlier in The New Yorker, Janet Malcolm wrote that ‘so strong is the identification of O’Keeffe with her photographed likeness that the photographs have seemed to belong among her works rather than among Stieglitz’s.’ While O’Keeffe was in town, she and Hamilton spoke with Andy Warhol for Interview magazine. Warhol recommended she visit the new AT&T building, but she refused, since the architect of 550 Madison Avenue ‘wasn’t really a talent’:

‘HAMILTON: You shouldn’t criticize Philip Johnson. He said you were the most beautiful woman in the world.

O’KEEFFE: Well, I didn’t think what he created was the most beautiful woman in the world.’

Warhol insists she see it anyway, but she won’t budge – after all, to see takes time.

Okay, that last bit is false – in the interview, which postdates O’Keeffe’s line about vision’s duration by four decades, Warhol just changes the subject – but it rings about as true as the phrase’s use as the title of MoMA’s current show. ‘Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time’ focuses on the artist’s iterative pastel, charcoal and watercolour works, with a few exceptions made for oil paintings on canvas that extend a paper-based series. The title comes from her catalogue text for a 1939 ‘Exhibition of Oil and Pastels’, and suggests the organising concept: that her ‘serial’ work creates the temporal conditions for really seeing. By emphasising procedure, materiality and small differences, this repetition of figure makes something visible.

But what? In her original artist’s statement, titled ‘About Myself’, O’Keeffe recommended not seriality, but stopping to smell the roses: ‘Still – in a way – nobody sees a flower – really – it is so small – we haven’t time – and to see takes time, like to have a friend takes time. If I could paint the flower exactly as I see it no one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small.’ O’Keeffe had been trying, by way of enlargement and by dignifying her own attention, not to represent the flower, but to coerce the viewer to participate in the time she spent considering it. In place of her vision, critics, with a new passion for sloppy Freudianism, saw cunts in the callas: ‘Well – I made you take time to look at what I saw and when you took time to really notice my flower, you hung all your own associations with flowers on my flower and you write about my flower as if I think and see what you think and see of the flower – and I don’t.’

‘To See Takes Time’ avoids this critical hang-up by neither referencing her reception nor including any of her more lurid stamens. That’s my guess, at least – that the show’s curators want to unburden the artist of her critical baggage. But in the place of Stieglitz’s false image of the turn-of-the-century New Woman, boldly reconciling abstraction with the sensual, we meet an equally fictional, peculiarly innocent girl.

The best justification for the curatorial focus appears at the entrance, in a trio of works on paper from 1916: First Drawing of the Blue Lines in charcoal; Black Lines in watercolour; and Blue Lines X in watercolour and pencil on paper. This strange trio are stubborn about their difference, the black of the charcoal having nothing in common with the pooling watercolour’s blue. Each, however, depicts the same thick base line at the bottom of the paper (say, the base of an abstract sailboat), from which grow the same two branches: erect on the right, zigzag on the left. They are terrific.

So are her ‘specials’ (1915–19), the title she gave to the works that stood out to her in this productive era. I admire the gross, mechanic blur of No. 20 – From Music – Special (1915), and its invitation to consider another 19 of them. If this is from a series, though, it’s in the loosest possible sense.

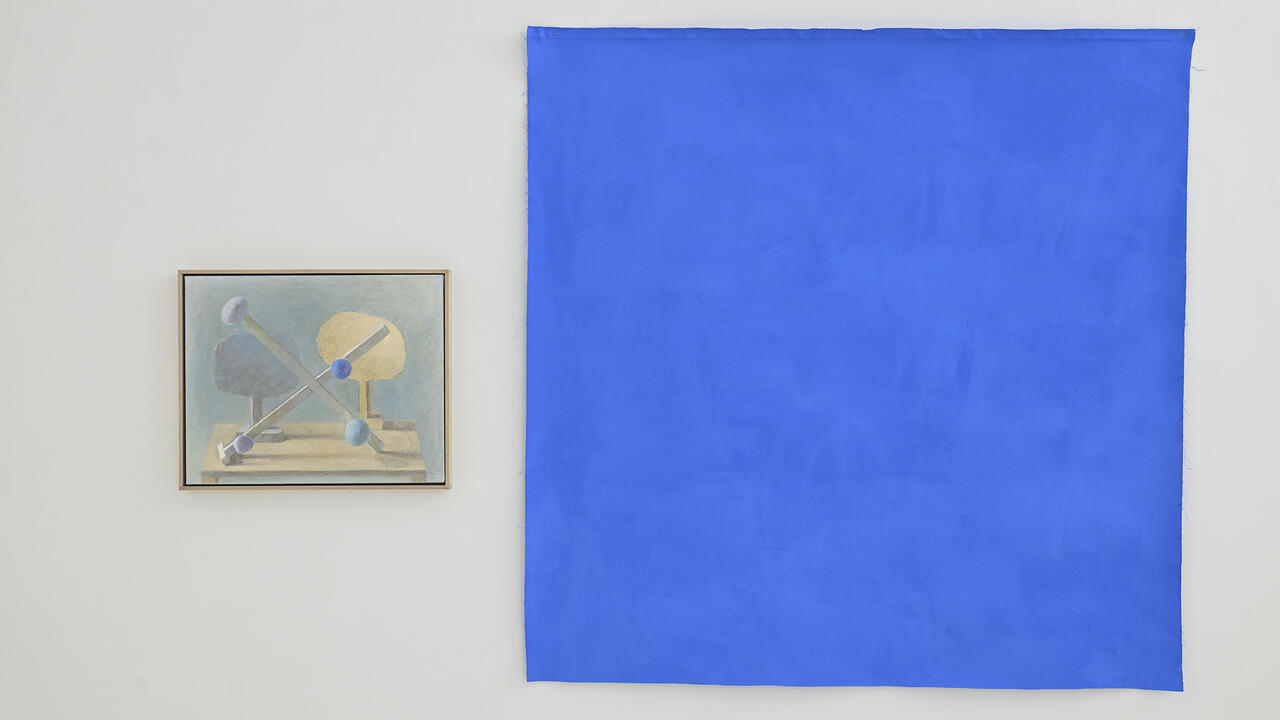

The abstract portraits of Paul Strand (1917) – here, a red-tailed caterpillar, standing upright against watercolour’s night sky – make for compelling companions to an interior wall devoted to O’Keeffe’s uncharacteristically realist charcoal portraits of Beauford Delaney (1943); together, they offer evidence for the artist’s sense that the subject itself demands its form. The focus on serial works on paper, though, quickly becomes frustrating. With all the polite modesty of chronological order, the curators try to convince someone that O’Keeffe was not that beloved painter of objectified flowers and bones, but instead a half-hearted minimalist.

The show seems to think little of its general audience. Converting banal snippets of her correspondence into section headings, the curators suggest it is some feminist feat, for example, that one of the defining artists of the 20th century had ‘SOMETHING TO SAY’. Of the watercolours, we learn nothing more than that ‘THEY KEPT COMING’. I recoil with personal horror, imagining someone finding a private letter in which I say there are ‘ALL SORTS OF THINGS IN MY HEAD’ and then using this vague phrase to posthumously frame my work. The wall text gives the sense that Georgia O’Keeffe was a brave girl with a lot to think about, and – thank god – a big stack of paper, so she could keep at the images until she got them right.

In Making and Effacing Art: Modern American Art in a Culture of Museums (1991), Philip Fisher argues that seriality ‘becomes a working tactic of the painter once he finds himself face to face with an intellectual world that articulates and surrounds his working life with a full-scale History of Art within which he is forced to see himself as an episode.’ For Sianne Ngai, who quotes Fisher in Our Aesthetic Categories: Zany, Cute, Interesting (2012), it is the critic who does that forcing, and for whom the serial, like ‘interesting’ art more broadly, offers purpose: this focus on process – and on meaning’s locus outside of the individual instance of a work – requires a bigger critical apparatus than does a huge, intense flower. ‘To See Takes Time’ tries to convert art that is big and spiritual into something small and material. Luckily, it doesn’t work.

‘Georgia O’Keeffe: To See Takes Time’ is on view at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA, until 12 August 2023.

Main Image: Georgia O’Keeffe, Evening Star No.III, 1917, watercolor on paper mounted on board, 23 × 30 cm. Courtesy: the Museum of Modern Art, New York. Mr. and Mrs. Donald B. Straus Fund, 1958. © 2022 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York