Hannah Höch’s Satirical Collages Are a Joyful Turn of the Knife

At Belvedere, Vienna, works by the German dadaist are placed in dialogue with avant-garde film of the era

At Belvedere, Vienna, works by the German dadaist are placed in dialogue with avant-garde film of the era

As a key figure of the 1920s avant-garde, German dadaist Hannah Höch was one of the first artists to engage with the power of images in the media. Her job with a major German publisher gave her access to piles of magazines, which she cut up and pieced together to make photomontages. While these works have been widely shown since Höch’s death in 1978, the intelligence of ‘Assembled Worlds’, currently on view at Vienna’s Belvedere, lies in making connections between Höch’s collages and her passion for avant-garde film of the era, with its comparable techniques of cutting, composition and montage.

As a cinema enthusiast, the artist was well-versed in the innovative ways in which form, structure and colour were tackled by visionary filmmakers of the era. In the period after World War I, montage became a way of disassembling a world in chaos to build revolutionary possibilities. Screened in the centre of the first room is Man with a Movie Camera (1929), an experimental silent film by Russian director Dziga Vertov, which Höch saw as one of the most important of her generation. A film as much about the process of filmmaking as it is about changing the world, its final sequence accelerates into a quick-fire of montaged images, with a speed that proposed seeing and experiencing the world in a completely new way.

Heads of State (1918–20) is an example of Höch utilizing montage for political satire. Its starting point is an unflattering photograph of two men in their swimming trunks – Friedrich Ebert, first president of the Weimar Republic, and Gustav Noske, minister of defence – which the artist layers with rhythmic, wave-like shapes and patterns of butterflies. The original photograph was already scandalous, causing lasting damage to the new democracy’s reputation, making Höch’s montage a joyful turn of the knife.

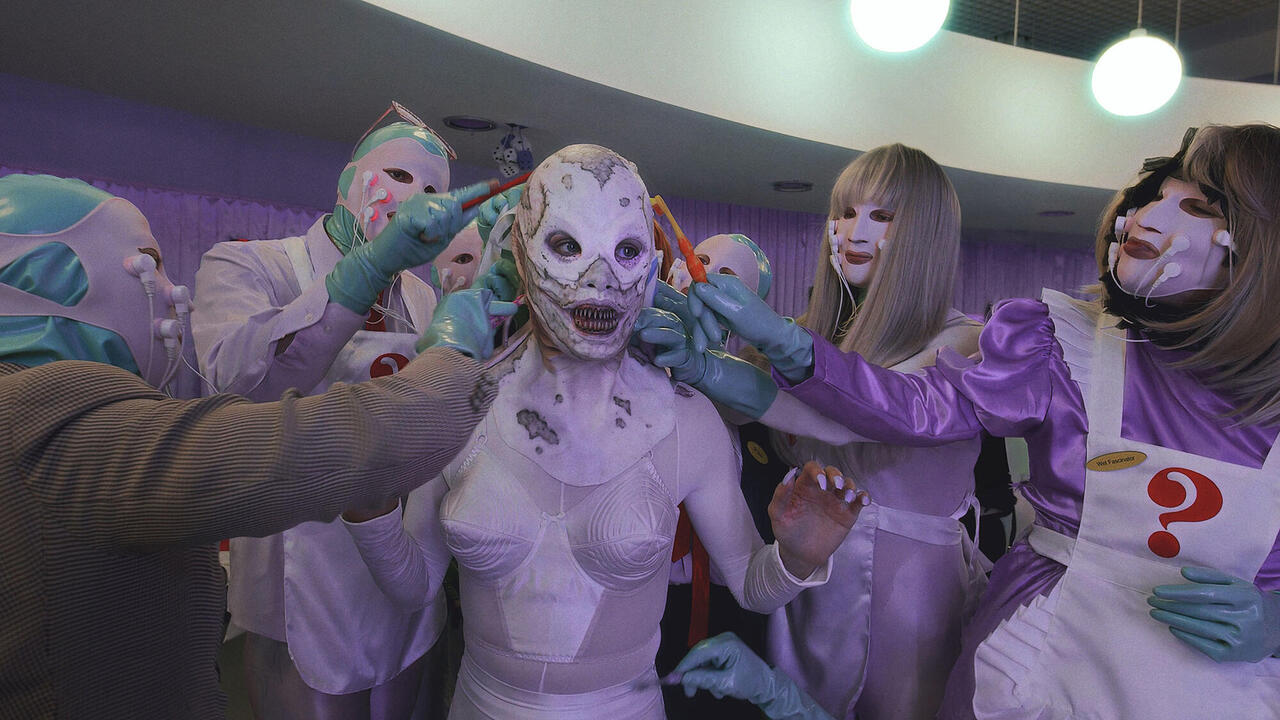

As a master of reassembling bodies, Höch often did so to unsettling effect, conjuring at once a sense of the horrific aftermath of war, the rise of fascism and an age of mass media dictating beauty standards. The collage Toughening Up (1925), for instance, drolly proposes strange, infantile bodies climbing apparatus at a time when physical training was popular in Germany – the strong athlete associated with the ideological goal of national cohesion and potency. Juxtaposed with Wilhelm Prager’s documentary Ways to Strength and Beauty (1925), the romanticized depictions of beauty in conformity with nature offsets Höch’s critique of such ideals.

A standout moment in the show is the connection between Fernand Léger’s Mechanical Ballet (1924), which translates cubism’s ideals into film, with Höch’s painted self-portrait, Cube (1926). Léger’s bodies blend with technological objects, merging as new shapes and multiplying in an electrifying mechanical dance that also speaks to the machinery of war, while Höch’s bizarre composition divides a face into three parts, a cube-shaped mirror surrounded by cogs and mechanisms, as well as bounteous plants and a curious cat, setting the stage for the new human in this age of technological progress.

Works by dada artists were branded ‘degenerate’ in Germany after 1933 – though Höch chose not to leave the county like some of her colleagues, moving instead to the Berlin suburb of Heiligensee, where she spent much of the rest of her life inventing fantastical worlds. Around a Red Mouth (1967), for example, conjures a luscious landscape of pastel strata, with lace and candy-coloured layers of rock swirling around a pair of smiling lips. And, while Höch’s later collages, which close the exhibition, often feature cats and plants – This Is not a Work of Art (undated) is deliriously comical in its combination of 15 cats with roses and daffodils – the rebellion inherent in Höch’s use of photomontage as a way of undermining convention remains unparalleled.

‘Hannah Höch: Assembled Worlds’ is on view at Belvedere, Vienna, until 6 October

Main image: Hannah Höch, Around a Red Mouth, 1967. Courtesy: © Bildrecht, Vienna 2024 and ifa art collection; photograph: © Christian Vagt