Henrik Olesen’s Timely Excavation of Gay Activist and Queer Histories

The Berlin-based artist’s mid-career retrospective at Spain’s Reina Sofía is a free and self-determining triumph

The Berlin-based artist’s mid-career retrospective at Spain’s Reina Sofía is a free and self-determining triumph

Soon after Henrik Olesen’s mid-career retrospective opened at the Reina Sofía, sad news emerged that critic Douglas Crimp had died. This, combined with the fiftieth anniversary of Stonewall the month prior, made Olesen’s exhibition especially timely in its reflection of gay activist history and queer legacy. Olesen draws from post-minimalist and conceptualist treatments of the body to examine the sexuality, psychology and de-legitimization of non-normative identities. He undeniably advances a queer aesthetic, but his practice is also gloriously nebulous: an ongoing experiment with the point at which ‘queer’ becomes inscrutable.

Curated by Barcelona-based art historian Helena Tatay, Olesen’s exhibition (containing works from 2001 to 2019) spanned appropriation (St. George and the Dragon, 2016), site-specific architectural interventions (Rechte Ecken (Straight Corners), 2019) and historically-researched displays. The artist is, perhaps, best known for the latter, gaining recognition in the early 2000s when the concept of ‘practice-based research’ was still relatively new. Early works, such as Lack of Information (2001) – which documents the criminalization of homosexuality around the world – reveal an indebtedness to the French philosopher Michel Foucault, whose ‘critical archaeology’ and genealogies of power had a subterranean influence on the trajectory of institutional critique. It’s an influence that traverses the documentary, systems-art practices of the 1970s, as well as their more identitarian varieties in the ‘90s, when Olesen was an art student in Copenhagen and Frankfurt am Main.

In Some Gay-Lesbian Artists and/or Artists relevant to Homo-Social Culture Born between c. 1300–1870 (2007), Olesen pays homage to Mnemosyne Atlas (1924–29), by legendary German art historian Aby Warburg. The work – two freestanding double-sided panels and a wall-mounted display – visually resembles Warburg’s dark, cloth-covered boards, but, instead of the ‘afterlife of antiquity’, it centres on male and female gay cultural history between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries: reproductions of paintings and sculptures, photographic portraits, medical illustrations, images of cross-dressing, sodomy and more. The edited arrangements refer (somewhat idealistically) to a time when homosexuality was fluidly communicated through innuendo and subtext, before becoming pathologized in modern times. Headings such as ‘American Male Bodies,’ ‘Paris Femmes,’ and ‘Anal Sex in England’ are anodyne and quasi-scientific, but what resonates are the pleasures of historical discovery and free association. Perched on top of one of the displays, two stuffed chickens (or are they cocks?) stare insouciantly off into the distance. Like the inclusion of a George Harrison poster in St. George And the Dragon – which recreates Anthony Caro’s red 1962 sculpture Early One Morning – it’s a characteristically delphic gesture by the artist, countering any expectations of research as a dry, intellectual exercise.

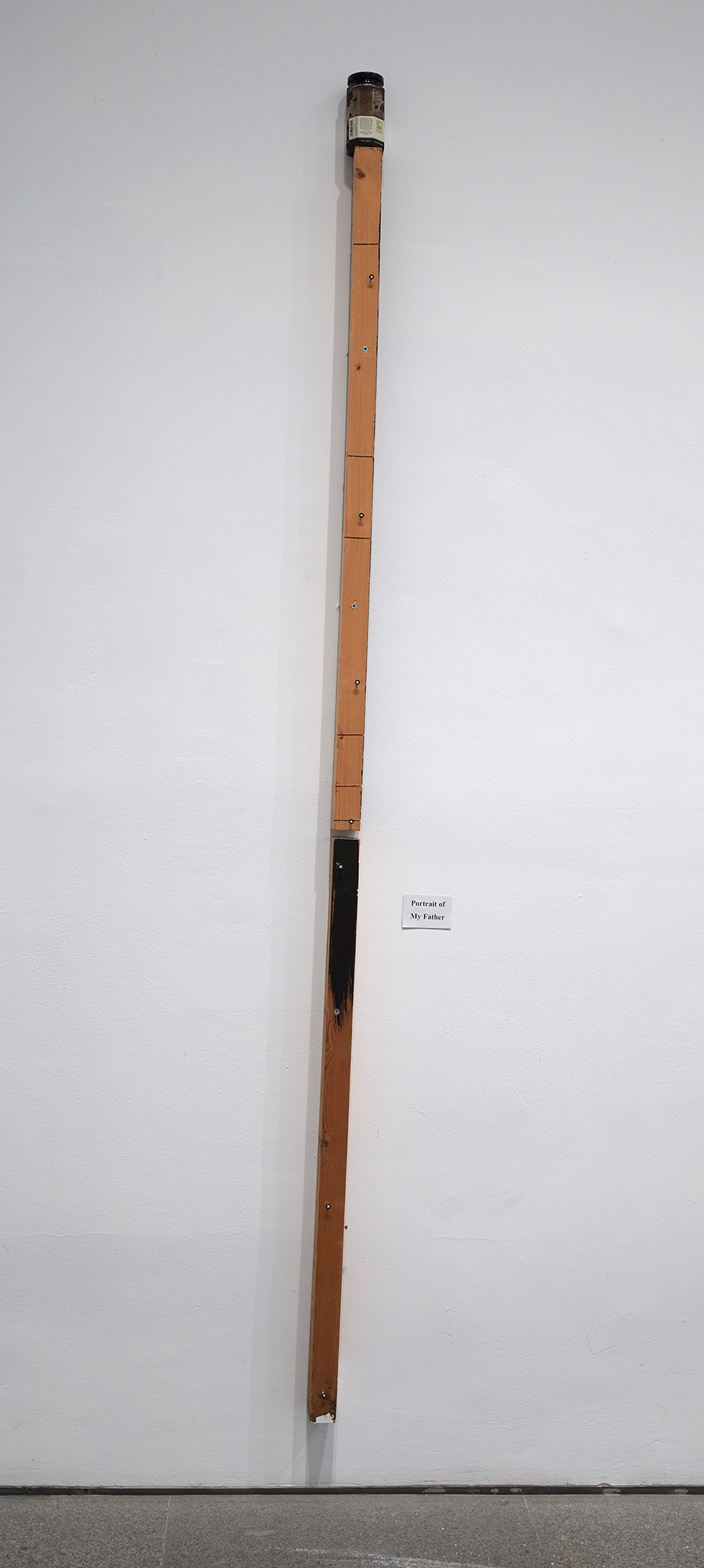

The exhibition’s numerous wooden structures, plexiglass containers and architectural edifices – the doorframe of Exit/Portal (2018) and the dioramic-like boxes of ‘Hey Panopticon! Hey Asymmetry’ (2018) – look designed for viewer interaction yet never lose their sense of melancholic incompletion. Other corporeal objects – a single black leather shoe attached to the museum’s ceiling, Agent (Shoe) (2008), and a portrait of the artist’s father made from two long pieces of wood and a jam jar, Mr. Knife and Mrs. Fork. Portrait of My Father (2009) – suggest authoritative bodies subjugated by architectural space, intensified by the show’s scattered references to punishment, flesh and bodily fluids. Restriction is important to Olesen, who, rather than try to expunge critical limitations (blindspots), implores viewers to confront them. It is to this end that the exhibition emphasized not information per se but the affective force of institutionalization.

In I Will Not Go to Work Today. I Don’t Think I Will Go Tomorrow (Machine-Assemblage) (2010), an Apple laptop that has been systematically dismembered and displayed on the wall is, via its title, imbued with first-person subjectivity. It’s a brilliant encapsulation of Olesen’s art and advocacy of gay identity: a free and self-determining declaration that seems almost miraculous when made under the coldest of gazes.

Main Image: Henrik Olesen, St. George and the Dragon, 2016, wood, metal, paint and text on paper, 600 × 226 × 240 cm. Courtesy: the artist and Scott Lorinsky Collection