Mourning and Melancholy in the History of Class Struggle in the Western US

The work of John Hanson, Rob Nilsson and Fred Lonidier establishes a dialectic between a leftist melancholy and a more forward-looking politics

The work of John Hanson, Rob Nilsson and Fred Lonidier establishes a dialectic between a leftist melancholy and a more forward-looking politics

Vast sky overhead, plains stretching toward the horizon – O, pioneers! For centuries, in the US, a myth of the West has been a cudgel to beat onward a national (and nationalist) idea of prosperity and freedom, wrested in blood. It’s a fairy tale largely told through popular films, television programmes and novels. In these stories, cowboys and homesteaders embody a loner ideal of rugged individualism inextricably linked to a surging free market, striking gold for Christ in the Mormon State of Deseret. But, against this perception of a boundless US interior, the actual political history of the Plains offers up countless examples of the limits capitalism has placed on the region and its political imagination. Given that much of this history plays almost no part in our popular images of the West, we might turn to recent and newly restored art and, in particular, film and photography, for images that re-assert the primacy of the working class in this region. These works also resist the melancholy that has been pervasive in the leftist retelling of the rise and fall of the US labour movement. There are two histories of the region – a landscape conjoined in desert, plains, beaches and old-growth forest, stretching west of the Mississippi to the glinting Pacific and curtailed only by the artificial borders with Canada and Mexico. First, one of so-called manifest destiny; second, one of work.

From the theologies of Mormons and Theosophists, who held that the spiritual future of the continent lay in the West, to the early hucksters of desert real estate, the Western US has long been associated, through propaganda and boosterism, with unrestricted access to resources and renewal through God and grit. In the 19th and 20th centuries, it was idealized in the landscape paintings of Frederic Remington and Charles M. Russell, the movies of John Wayne, the novels of Zane Grey and in countless other media, from wide-reaching radio sermons to comics. But this popular history contains a paradox: as big and endless as the West apparently was, from a capitalist perspective, it also needed to be tamed. Construction of railroads in the 19th century by underpaid Chinese, black and Irish workers; farm-steading on the land of displaced peoples that often amounted to legalized serfdom in the early 20th century; urban development across the expansive Sun Belt in the 1980s (at enormous ecological expense, and often bought with subprime mortgages, leading to the 2008 housing crisis); the plumbing of desert to build Palm Springs and Las Vegas: this is another history, one defined by the unfettered exploitation of labour.

John Hanson and Rob Nilsson’s documentary series ‘Prairie Trilogy’ (1978–80), which was recently restored and screened at the Metrograph theatre in New York this summer, focuses on a 97-year-old socialist, Henry Martinson, from North Dakota. The son of Norwegian immigrants, Martinson served as recording secretary for the Fargo Labor Assembly and saw North Dakota’s branch of the Socialist Party of America, led by Arthur C. Townley, re-invent itself as the Nonpartisan League (NPL) in 1915. The following year, the NPL won control of the state and implemented a socialist government that granted women the right to vote, introduced workers’ compensation, a graduated income tax, a state-funded insurance programme and several other bureaus focused on the improvement of North Dakotans’ lives. (NPL activities spread to 11 other states.) And then, through the machinations of greater political forces, it was over: the state recalled its governor in 1921 and pro-business government was restored.

Funded in part by the North Dakota Humanities Council and the state’s federation of unions (the AFL-CIO), ‘Prairie Trilogy’ – which was shot entirely in black and white – begins with Prairie Fire (1978), a short, documentary presentation narrated by Martinson that follows the rise of socialism in North Dakota following an uprising of farmers against capitalists ‘back east’. (The film uses period footage shot by Nilsson’s grandfather.) The second film, Rebel Earth (1979), centres on the relationship between Martinson and a younger farmer named Jon Ness, who shares the older man’s frustrations with capitalism but finds himself with no political vehicle to do anything about it. The final instalment, Survivor (1980), focuses solely on Martinson at his summer home, among friends from the NPL and, in one stark scene, in the abandoned, snow-filled farmhouse where the League was founded. Socialism equals optimism, Martinson tells us, and, despite the crippling anti-labour initiatives of the past 100 years – he and other members blame the 1933–36 New Deal for centralizing progressivism in Washington and for the red-baiting of the McCarthy era – he remains hopeful. The final scene shows Martinson walking down a pier, toward a wind-beaten lake. ‘I believe a socialist regime is as sure to come as daylight comes after dark,’ he tells us. Martinson died in November 1981, ten months after Ronald Reagan became president and introduced sweeping legislation to privatize and deregulate remaining US industries. Night followed night.

Watching Martinson is like glimpsing a kindly poltergeist gleefully tossing furniture about the room; history, in his hands, is not what we know it to be. More importantly, in the stark black and white footage of his recollections of a red past (‘You can’t find a better colour than red’), his arguments with fellow farmers and his singing of farm songs with fellow Norwegians, he offers an image in contrast to the persistent gloom that dominates leftist views of history. The left has long dwelt romantically on its defeat in the major political struggles of the 19th century. Walter Benjamin first diagnosed ‘left-wing melancholy’ in 1931 when he wrote, in a book review for Die Gesellschaft, that the left had been absorbed with a fatalist view that saw no path forward; he compared it to a man who ‘yields himself up entirely to the inscrutable accidents of his digestion’. Political theorist Wendy Brown builds on Benjamin’s notion in her important 1999 essay, ‘Resisting Left Melancholy’, writing that the left ‘has become more attached to its impossibility than to its potential fruitfulness’. She adds that this ‘attachment to the object of one’s sorrowful loss supersedes any desire to recover from this loss […] This is what renders melancholia a persistent condition, a state, indeed, a structure of desire, rather than a transient response to death or loss.’ The late British theorist Mark Fisher summarized this melancholic as someone ‘who doesn’t recognize that he has given up’; what is missing, he writes in Ghosts of My Life (2014), is ‘a trajectory’.

The ‘Prairie Trilogy’ trades in some leftist nostalgia – particularly through Ness, for whom Martinson appears to serve as a sorrowful embodiment of that insurmountable loss in the face of a relentless capitalist reality. (In this, I believe, we are invited to see, and reject, Ness as a stand-in for our predisposition to melancholy.) However, it ultimately offers up Martinson as an optimistic courier of a lost history that might be carried forward, rather than mourned. Optimism here is not merely cheery feeling for a better tomorrow; it is, instead, an affirmative belief in a path, a faith in the restoration of that absent trajectory. Perhaps the most engaging part of the trilogy is not the history it rediscovers in Martinson’s early years as a socialist, but in his view of the future as one of coming daylight.

This year has seen an aggressive push, by Donald Trump’s administration, against workers’ rights – from the removal of protections for LGBT employees to the Janus v. AFSCME Supreme Court case in June, which held that public sector unions could not collect fees from non-members even though they still benefit from union-led contract negotiations. As a result of the ruling, unions now expect to lose 30 percent of their membership and millions of dollars. (Night gets darker.) In March, New York’s Essex Street gallery presented Fred Lonidier’s ‘Two Works from the 1980s’, which included the important installations he made in relation to – and for – unions in California. In these works, Lonidier, like Hanson and Nilsson, establishes a dialectic between a leftist melancholy and a more forward-looking politics. L.A. Public Workers Point to Some Problems (1980), a multi-panel, wall-based work, quotes first-hand accounts from Los Angeles’s public workers. They indicate on-site problems and highlight the bleak future that some key union-held sectors, such as education, faced at the time. One representative panel includes, on its left side, the outline of the employment conditions of Deborah Badger, a member of the United Teachers union and, on the right, italicized pull-quotes from her interview. ‘Every day and every week it’s getting worse,’ she says. Black and white images depict Badger with her students alongside examples of those aspects of her job that were worsening at the time, from a pothole-filled playground to basic classroom items that she had to buy for her students. ‘After a while, you get tired of fighting.’

L.A. Public Workers was set in contrast to I Like Everything Nothing but Union (1983), a panel work commissioned by the San Diego AFL-CIO for its offices (and which is still on view there) that asserts the positive role unions play in communities. The installation shows a number of workers from around San Diego, emphasizing the broad racial and gender diversity of individuals who belong to the unions affiliated with the AFL-CIO. Musician Don Carney grins beside a drum kit (Musicians Association of San Diego County Local 325), Juanita Whetstone and Pat Harte-Johnson sit happily with their typewriters (Office and Professional Employees International Union Local 139) and Rich Koreerat leans against his bar (Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees Union Local 30). Dozens of such photographs – all black and white, shot at work – appear throughout the installation. These vernacular, unassuming images manage to capture not just the labourers themselves, but a certain self-possessed confidence afforded by hard-earned employment protections.

Benjamin diagnoses the left melancholic’s problem as his or her stupefying investment in ‘things’, which he identifies, in The Origin of German Tragic Drama (1928), as the ‘dead objects’ of knowledge (as opposed to truth). In his aforementioned 1931 review for Die Gesellschaft, Benjamin describes this investment as ‘pride in the traces of former spiritual goods’. In ‘Resisting Left Melancholy’, Brown traces Benjamin’s thinking on the subject and adds that ‘left-wing melancholy’ loves ‘our left passions and reasons, our left analyses and convictions, more than we love the existing world we presumably seek to alter with these terms or the future that would be aligned with them’. In foregrounding the practical reality of union success and peril in the face of an aggressive conservative movement, Lonidier’s ‘factographic art’, as Benjamin H.D. Buchloh termed it in a 1984 essay, rejects the museum- and gallery-based ‘system of representation that we traditionally refer to as “the aesthetic”, [which] by definition extracts itself […] from the economic and political reality of the basis of culture in everyday life.’ Instead, Lonidier ‘counteracts this tendency’ by ‘exploring the basis of [that] culture, i.e., labour.’ Lonidier mobilizes information and photography toward an art that campaigns and petitions; an art that, like Martinson, sees in the labour movement a workable present and a viable future. Not a trace, but a trajectory.

The original exhibition spaces for Lonidier’s work disappeared when unions sold their permanent buildings in favour of rented spaces beginning in the 1970s and ’80s. (The artist did not exhibit in a commercial gallery until 2011.) ‘I am a historical artist now,’ he told me one recent afternoon. When I asked him if he thought his work retained its relevance, despite the dismantling of the power of US unions, he answered emphatically: ‘Yes.’ Like Martinson, he sees the class struggle as ‘continuous’, even as the familiar settings for that struggle – construction ites in San Diego, for example – have dispersed to the manufacturing centres in the global south and away from a strong labour movement. In 2018, Lonidier views the lessons of the past as essentially the same for the present and future, and he believes the issues raised by his work ‘would resonate with any worker anywhere, any time. Now. Today. Then. Fifty years before that.’ Lonidier is currently working on a photobook that collects images of and texts by his late sister, the poet Lynn Lonidier, who died in 1993. It will be his most personal work to date and will be shown in conjunction with the publication of her collected poems.

‘The struggles I’ve represented go on and will go on,’ he told me. I thought of a line by Gertrude Stein: ‘Let me recite what history teaches. History teaches.’

John Hanson lives in Bayfield, USA. With Rob Nilsson, he directed Northern Lights (1978), which won the Palme d’Or at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, France. He was a founding member of San Francisco’s Cine Manifest, a collective of Marxist filmmakers. Fred Lonidier lives in San Diego, USA. In 2018, he had a solo show at Essex Street, New York, USA. In 2017, his series ‘N.A.F.T.A. (Not a Fair Trade for All)’ was exhibited for the first time in Europe at Kunstbunker, Nürnberg, Germany. Rob Nilsson lives in San Francisco, USA. With John Hanson, he directed Northern Lights (1978), which won the Palme d’Or at the 1979 Cannes Film Festival, France. His most recent film, The Fourth Movement, was released in 2017. He was a founding member of San Francisco’s Cine Manifest, a collective of Marxist filmmakers.

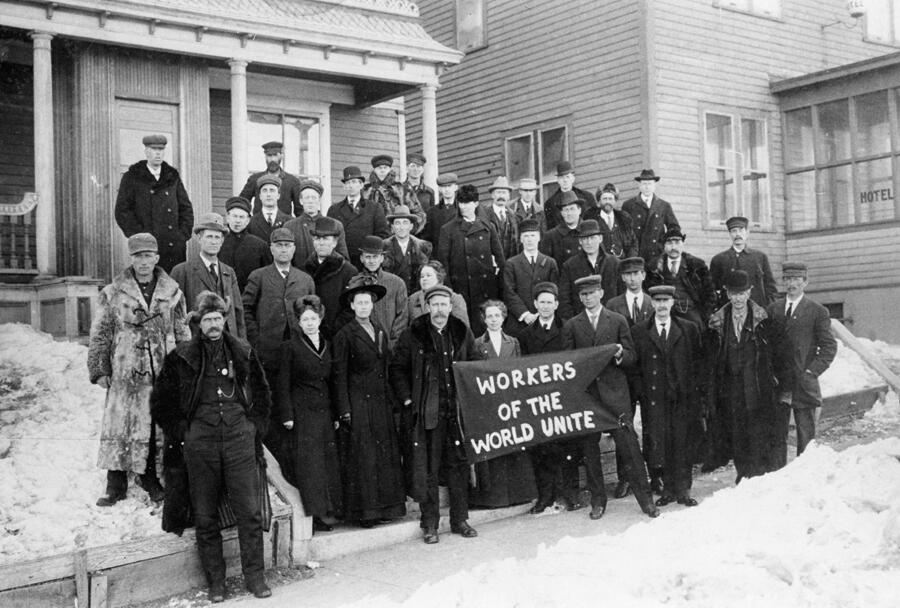

Main image: John Hanson and Rob Nilsson, 'Prairie Trilogy', 1978-80, film still. Courtesy: Metrograph, New York, and Northern Pictures & Citizen Cinema