‘History is a Continuous Movement’: An Interview with Simone Fattal

Negar Azimi visits the Damascus-born artist ahead of her retrospective at MoMA PS1

Negar Azimi visits the Damascus-born artist ahead of her retrospective at MoMA PS1

Simone Fattal has a sonorous, sexy voice, her English tinged with accents of French and Arabic. High cheekbones punctuate an angular face that seems to have been chiselled from stone. It’s the same ravishing face you see in Autoportrait (1971/2012) – an impish, tender, filmic self-portrait of its author at the age of 30 – which premiered in 2012 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art after 40 years in unfinished limbo.

The Syrian-born artist has made only one film, but her practice is protean, spanning painting, sculpture, translation and publishing. Life, too, has been itinerant; since leaving Damascus as a child, she has called France, the UK, the US and Lebanon home. She founded Post-Apollo Press – publisher of adventurous, experimental titles – in 1982, during a season in the northern California hamlet of Sausalito. Why Post-Apollo? ‘Because I thought the world would forever change after the moon landing.’

Fattal is also half of one of the most interesting couples I know. For 46 years, she has made her life with the poet and painter Etel Adnan. They share an apartment in Paris’s Latin Quarter, a few minutes’ walk from Fattal’s studio on Rue Notre-Dame des Champs, a light-filled space stuffed with her crowded collages and smudged sculptures, which intimate antiquity and wry modernity at the same time. You can almost hear the ghosts of this storied neighbourhood murmuring their appreciation of Adnan and Fattal’s zigzagging, bohemian alliance. ‘Works and Days’, Fattal’s current solo exhibition, is on view at MoMA PS1 in New York.

Negar Azimi Simone, you recently sold the California house that you and Etel lived in for years.

Simone Fattal It was horrible. The hardest thing. We bought that house in 1980 and lived there for 30 years, so it’s been a whole life.

NA My father lives not far away, in Berkeley, so I know the area and its magic. It’s a slice of heaven.

SF It is. We had the best view – of Mount Tamalpais and the San Francisco Bay. There was a little garden that we loved, too. Etel wrote an extraordinary poem about it called ‘The Spring Flowers Own’ (1990). The house was built on stilts, so the whole ground floor was open. I built my office downstairs and used it as a warehouse for books. Post-Apollo started there. It was a gift.

NA California is also where you started making sculpture.

SF Yes, I’d been a painter in Lebanon. I painted for ten years but I lost much of that work when the Lebanese civil war forced us to move.

NA Can we go back in time, to 1969, the date of the earliest piece in ‘Works and Days’? You’d just returned to Lebanon from Paris, where you had been studying philosophy at

the Sorbonne.

SF I knew I didn’t want to go into academia and I was looking for something else. I had started doing watercolours, but casually, with friends. My mother was away at the time, so I settled myself in the dining room with oils. When she came back she said: ‘Hey, you’re ruining my carpets!’ So, I rented a studio of my own and moved there. I lived alone, which nobody did at the time. Not men, not anyone.

NA You were an iconoclast. Where was the studio?

SF In [the East Beirut neighbourhood of] Achrafieh. I had a roof. Interesting people had roofs. On the roof, there was a small apartment with two rooms and a living room. I had a big mirror and a bar for dancing, just like the one I have here. [Walks over to the bar and performs some exercises.]

NA Like a ballerina!

SF I did ballet. There was a big wall I could paint on, too. I always painted standing up. I lived there until 1974, then I moved again, also to a top-floor studio, this time with a perfect view of Mount Sannine.

NA What were those first paintings like?

SF The first paintings were like self-discovery, like being born. They were very colourful, very lush, probably because I would go to the forests of the Chouf District for inspiration. But, little by little, my attachment to colour evolved into a fascination with white. I remember the painter Paul Guiragossian came to see me and said: ‘Of course you paint in white, all you see is light here on the 11th floor.’

NA Those paintings feel like the visions of someone perched up high, looking out at the world. So, you had no formal training but you were spending time with painters?

SF Exactly. I found my way.

NA Beirut was enormously exciting at the time.

SF Politics is always present in Beirut, you can’t escape it. When I got back, the Six-Day War of 1967 had just ended and the civil strife between the Palestinians and the Lebanese Forces was just beginning. At the same time, there was a vibrant scene with painters and writers and intellectuals and chic parties and so on. We were extremely carefree.

NA The city was a publishing centre, too.

SF It was. What’s the old expression? Egypt writes, Lebanon publishes, Iraq reads ...

NA If only that were still true. Can you tell me about your milieu?

SF Fadi Barrage was one of my closest friends. He was a painter.

NA Fadi was in your film, Autoportrait, yes?

SF He was. He later moved to Athens, where he died in 1988. In addition to Guiragossian, there was Huguette Caland and, of course, Etel. I met Etel at the end of 1972, when she came to Beirut to be the culture editor of the Lebanese newspaper, Al Safa. Who else? Wadeh Fares, who ran a gallery.

NA Was it Gallery One?

SF No, his was called Contact Gallery. Gallery One was the first gallery in Beirut. I had my first show there in 1973, with Etel. We worked on a book together and I made paintings around her poem, ‘Five Senses for One Death’ [1969], which Yusuf al-Khal, the founder of the gallery, translated into Arabic.

NA That’s right. Al-Khal founded the modernist journal Shi’r [Poetry, 1957–70] years before. I remember Etel telling me that it was Shi’r and Al-Khal that motivated her toreturn to Lebanon after years of being away.

SF Yes! He told her: ‘We’re waiting for you here!’ Shi’r was the most influential literary magazine in the Arab world. Besides publishing all the Arab modernists, Yusuf translated and published the most innovative European writers into Arabic. It was a rich moment. His gallery became a kind of salon.

NA We’ve spoken in the past about how you collect visual scraps that, in turn, feed your work.

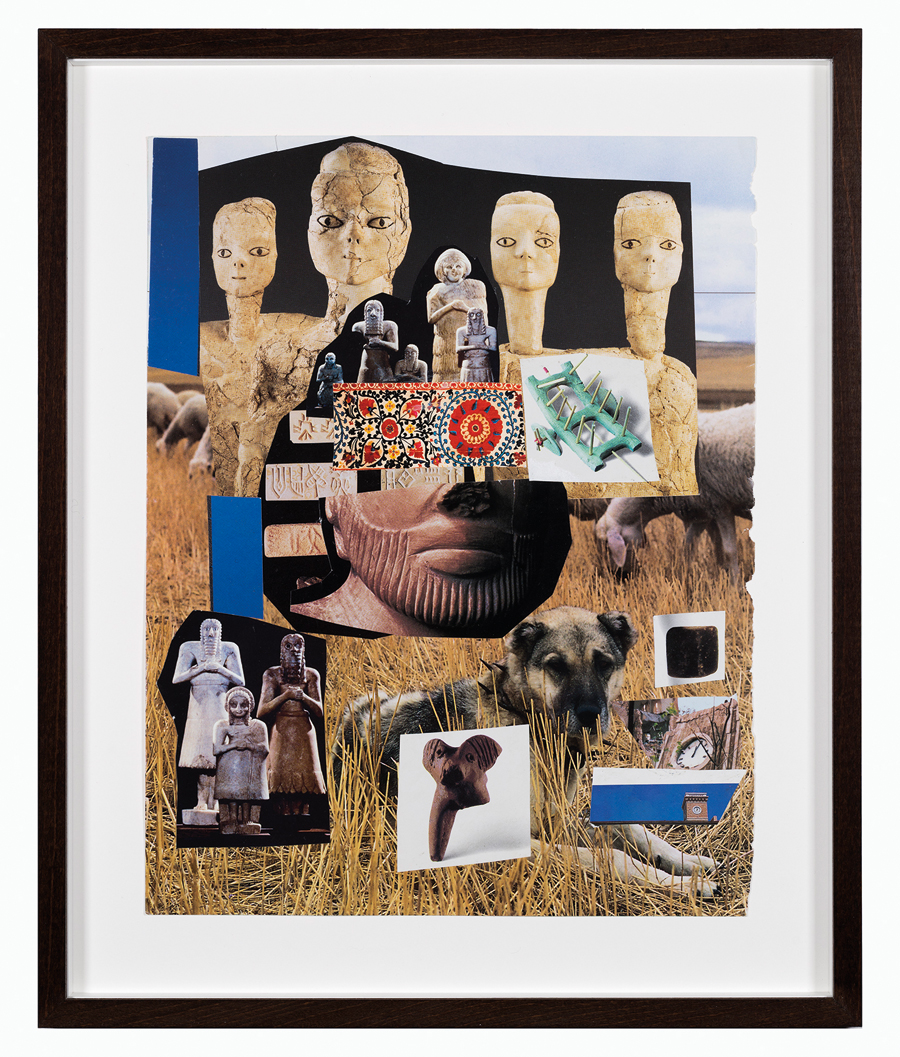

SF If you were to pick up one of my earlier collages, you might find the centaur, a recurring theme, or Ulysses. There are elements of archaeology, Islamic and pre-Islamic art and modern art throughout. And, of course, everyday politics.

NA When did you start making collages?

SF I started in California, so a very long time ago. The first one I made was very small and about the luxurious environment in which we lived with trees and so on. On top of this luxury, I depicted the horrible environment in which the Palestinian refugees live, amidst rubble and stone.

NA Your source material is often magazines, newspapers.

SF Most of these images are from Aramco World magazine. [Picks up collages.] Here’s one with my own portrait. Here’s Marino Marini, the Italian sculptor, and here’s Ulysses, again, with his chariots.

NA You’re very taken with the ancient world.

SF When I first arrived in Paris for my studies, it was late in the year and I could no longer enrol at the Sorbonne. The only school I could register at was the École du Louvre, which has a special focus on archaeology. The experience must have affected me because, years later, when I touched clay, it was as if all that history came rushing back.

NA Can you tell me about the first clay piece?

SF In my first clay class at the College of Marin in California, I made a man: a standing figure with no head and a torso that was diagonally inclined. I glazed him grey. When I saw that colour, I became hooked, because colour shines on clay. No painting can give you this colour.

NA Who was this man?

SF It looked exactly like the broken torsos found on archaeological sites, so I told myself that I had come across this ancient-looking man, this warrior, in downtown Beirut in the middle of the civil war. So, from the very first piece, there was this relationship to the past, this meeting between the ancient and the modern.

NA Your figures’ legs are often thick, sturdy. They look almost like tree trunks.

SF Some people see trees, others see doors.

NA In the Middle East, you see a door and there may be 3,000 years of history behind it. The past is vivid, always present. Living in the US, your eyes must have been starved for antiquity.

SF In America, a wall is a wall, period! Nothing more. It was a shock.

NA Do you think it was longing that made you gravitate toward the past?

SF It must have been. I can’t explain it. The second piece I made was a bronze of Adam. Later, I made Eve. I was reading about Sufism and philosophy at the time and, in Islamic mysticism, Adam is very tall, so I made these legs very long.

NA That seemed to become an imprint for all the men that followed. With their atrophied heads and textured bodies, these figures feel as though they’ve weathered a great storm. They’re survivors, of a sort. You’ve said yourself that many are warriors. Are they romantic figures?

SF Not at all, but they are witnesses.

NA In the same way that a tree is a witness. What they say to me is: ‘I won’t disappear.’ There’s a resilience about them. Can we talk a little about Damascus, your birthplace?

SF Damascus is my lost paradise. I was taken away at 11 to be sent to boarding school. It’s still my greatest sorrow.

NA Where was boarding school?

SF Beirut. It was a terrible, strict school. No heating, horrible food, we never went out. I was very unhappy. I loved my teachers, I was good at my studies, but the nuns were horrible. Sadists, I would say. They always wanted to put you down. I developed jaundice, I was so miserable!

NA But you stayed?

SF I stayed. It was my mother’s decision. They thought it was the thing to do. She’d been unhappy in such a school too.

NA The daughter suffers like her mother before her! What was the Damascus of your youth like?

SF The gardened city was still very small at that time, as in ancient times. You could climb up Mount Qasioun and look down and you’d see a ring of orchards, olive trees and fruit trees below. It was quiet when you entered Damascus – there was this tremendous silence in the evening. It was mysterious. There was an extraordinary sense of history. The river Barada ran through the city – it’s disappearing. My grandfather had a big farm, it was called Boustan El Leil.

NA That’s nice: ‘the garden of the night’, in Arabic. You speak of an overwhelming awareness of history. You read widely and you often work on epic historical texts – the Koran, Sumerian tales, Ibn Arabi, Sufi mysticism …

SF Because they’re extraordinary literary marvels. The Sumerian poems are amazing. I love the ‘Epic of Gilgamesh’ [c.2100 BCE], the story of one man’s failed quest for immortality. I also covet poems from Ugarit, a city in northern Syria near the Mediterranean where the first alphabet was invented. There’s the epic of Zaat el Hima, also …

NA Tell me about Zaat el Hima.

SF It’s the story of a female knight who defends the new caliphate against the Byzantine world. She fights alongside her son, Abdel Wahab. It’s fantastic: eight volumes of 1,000 pages, each probably written during the time of One Thousand and One Nights, but it remains mostly unknown. I’ve created a whole set of characters based on it.

NA These stories from the past accompany you in the present.

SF I see history as a continuous movement. Besides, these stories were never shared with us! As a child in Damascus, the oldest stories we could access went back to the Islamic conquest only.

NA You’re involved in a recovery of a sort. I feel like this instinct of yours also found a home in the kinds of books that Post-Apollo published, many of them rare or otherwise homeless. When was the last time you were in Damascus?

SF It was just before the 2011 uprising and, you know, I felt something strange. I felt that I wouldn’t want to go back …

NA Do you follow the news?

SF I do. The pillaging of Palmyra two years ago was an unbelievable catastrophe. When I see the refugees in the sea, it’s as if I’m witnessing the disappearance of our language.

NA Destruction and conflict have long simmered in the background of your life and art. What is your first memory of war?

SF It must have been in 1948, when I was a child. I could hear a French voice on the radio speaking of Les Sionistes, but I didn’t know what that meant. Then, in 1956, the French, English and Israelis invaded Egypt. Even in Damascus, we put blue on all the lamps to dim them so they wouldn’t be seen in a raid. We felt we had been attacked, too.

NA During the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, you were in Paris.

SF I was. It was a turning point in my life because of the French attitude towards us. You would buy a newspaper and the guy would say: ‘Go buy your newspaper somewhere else!’ It was impossible not to feel your identity more strongly. In many ways, I became an Arab that year in Paris.

NA Your work, in a way, is what Hans Ulrich Obrist calls a protest against forgetting. It’s more than lugubrious lament.

SF There’s no lament. I hope my work might say, to future generations: ‘We gave a good fight.’

This article first appeared in frieze issue 202 with the headline ‘Some See Trees, Others See Doors’

Main image: Alexander the Great, 2011, collage, 69 × 96 cm. Courtesy: the artist, Balice Hertling, Paris, Karma International, Zurich/Los Angeles, Kaufmann Repetto, Milan, and Galerie Tanit, Beirut; photograph: Francois Doury